To be really free feels like catching lightning in a bottle—exhilarating and extraordinary, yet fleeting. Hard to capture once, and if let go, even harder to get back. What if freedom wasn’t something to chase or remember, but something to live in, every day, with boldness and intention? In a world that tried to limit her imagination, Nellie Mae Rowe insisted on creating anyway, turning everyday materials into portals of possibility, and carving out joy in even the smallest scraps of time. Through the Playhouse—her home which doubled as an ongoing art exhibition open to the public—and her vibrant, often spiritually infused artwork, Rowe wasn’t just creating—she was reclaiming. Each piece became a sacred gesture, a return to the divine joy of her girlhood. In this space, art and faith intertwined, and her hands became instruments of devotion. Her Playhouse stood as a living altar where God, memory, and imagination converged, allowing her to recapture the freedom of her younger self—unburdened, unfiltered, and wholly beloved.

Born in 1900 in Fayette County, Georgia, Rowe came from a lineage of makers. Her mother, Luella Swanson, was a skilled quilter and seamstress; her father, Sam Williams, was a respected basket weaver, blacksmith, and farmer. Even as a child working on the family’s farm in Fayette County, GA, she carved out space for imaginative play. She drew lying belly down on the floor. She fashioned dolls from dirty laundry. She fashioned playhouses under the pine trees to host her creations—this was the first iteration of the playhouse. In these stolen moments, amid the backdrop of Jim Crow, manual labor, and systemic limitation, Rowe experienced the freedom to express, to imagine, and to build a world of her own. A world not defined by hardship, but by possibility.

At seventeen, she married and was widowed twice. She spent years as a uniformed “domestic” worker in white households. Her life was shaped by segregation, oppression, and labor, eventually halting her artistic practice altogether for 30 years. It wasn’t until the death of her second husband that she returned to art.

In September 2021, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta opened Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe. It was the first major exhibition of her work in over two decades, and the first to frame her practice within the context of the post-Civil Rights era South. This framing pushed against the narrow lens through which Black art, and especially Black folk art, is often viewed.

Historically, the museum and gallery space has been unwelcoming to any artists that do not find themselves within the rigid confines of eurocentric, elitist standards. Black folk artists, like Nellie Mae Rowe, who were self-taught or received their artistic training via knowledge passed down generationally or communally, were immediately labeled as unsophisticated, non-academic, and primitive.[1] The salvaged and repurposed materials used by Rowe and her counterparts represented a break from the classical art and traditional mediums, prioritizing storytelling through items that reflected their personal and communal experiences. Salvaged materials are more than just economic decisions; they give context to the culture this art emerged from. The context and reverence given to Rowe’s art in this exhibition was unique for folk art. After the exhibition formally closed at the High, I returned months later and encountered a partial display that remained. Though smaller, it still held so much of Rowe’s magic. That lingering presence led me to seek out the exhibition again, this time in its new home at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. That moment of return became a pilgrimage—a call across states, spaces, and time.

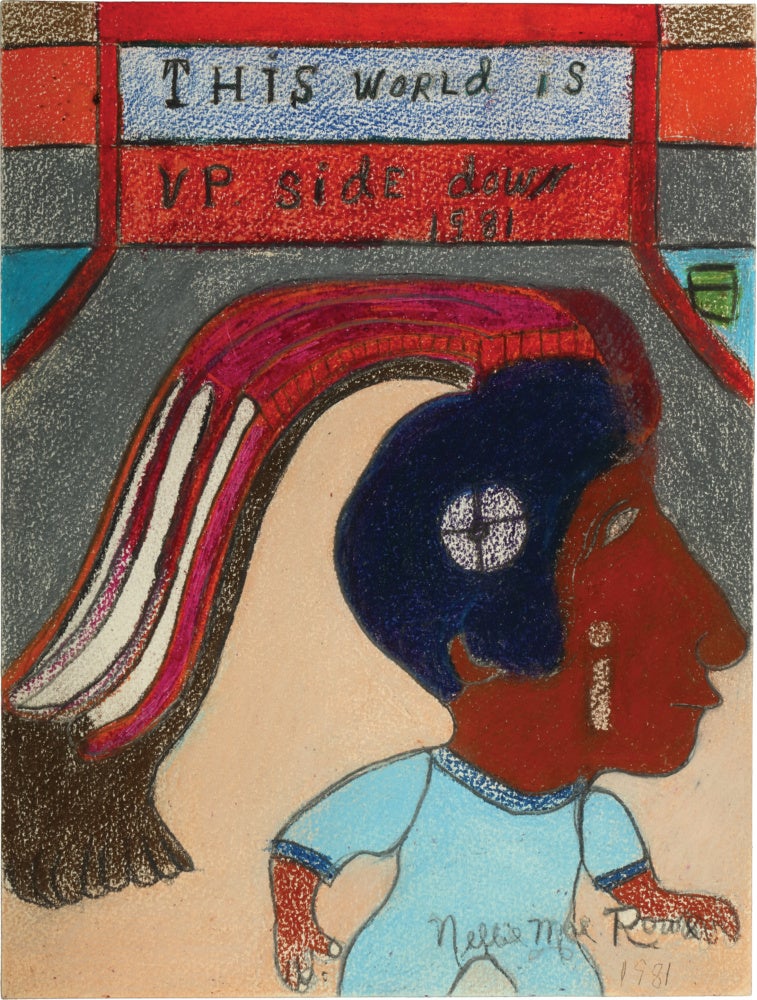

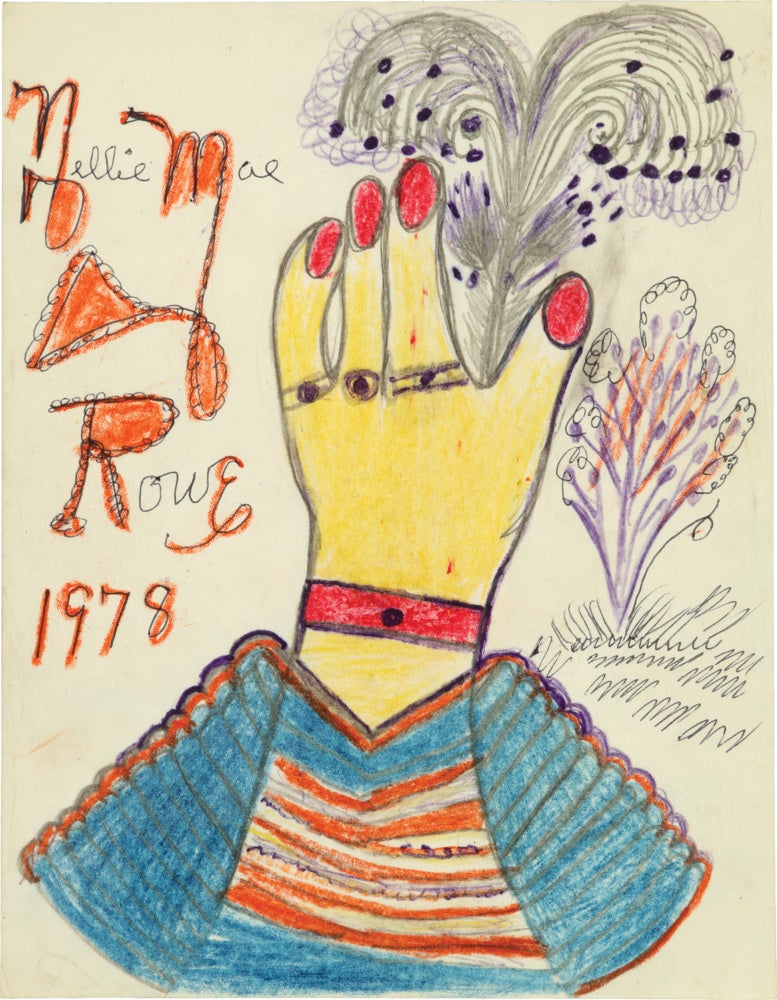

Rowe’s drawings are lush, layered, and saturated with color and meaning. Reality and imagination, spirit and memory, pain and joy—these elements blur together on every surface she touches. Each piece feels like a dream, a diary, and a prayer all at once. Untitled (Nellie Mae Making It to Church Barefoot) 1978-82. is heavily saturated in crayon. A pink, blue, and orange church sits at the end of a dirt path with large stained-glass windows surrounded by almost psychedelic green and blue trees. Below the church and walking up the path are two large brown feet, almost the size of the building, with pink toenails. The church is Flat Rock African Methodist Church, where Rowe attended church services and school in Fayette County, Georgia. Rowe would walk to this church countless times and at times, would take the journey barefoot, discarding the new shoes that would swell and pain her feet. Rowe would draw the image of her daily rituals with a surreal amount of imagination. She was laid to rest in the church’s historic graveyard, also depicted in this piece, in 1982.

Ironically, the piece that most greatly summed up the purpose of her body of work was the simplest. Untitled (Really Free!) 1967-76 is simply the frontispiece of Really Free!, a pamphlet reproducing the Gospel according to John, printed by the Bible Society in 1967. The words “Really Free!” are written in bold, italic print to the right side of the page. Rowe’s iconically large signature takes up the rest of the page, wrapping around the title text, with each letter finished with a flourish. For a Black woman of her time to boldly say she deserved to possess and share her love of herself, the right to creativity, her connection to God, it was an act of reclamation. Yet, Rowe’s most daring and defiant work wasn’t confined to the page or gallery—it lived in The Playhouse, her home in Vinings, Georgia.

print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Gift of the artist. Image courtesy of the California African American Museum, Los Angeles.

The Playhouse was a full-body experience: a garden, a gallery, a spirit-filled sanctuary. It was the physical manifestation of every scrap of girlhood and joy Rowe once cultivated under pine trees in Fayette County during her childhood. In it, Rowe found a way to preserve the same kind of sacred play she knew as a child, now rendered with the full intention and authority of adulthood.

A black and white photograph titled Nellie Mae Rowe, Vinings, Georgia (1971) captures Rowe outside The Playhouse, leaning casually against a fence decoratively weaved with ribbon, a possible tribute to her basket weaving father. Bottle caps shine on the dirt pathway, intentionally worn into the ground to serve as a decorative tile. At the end, a string of decorative bells and crystal trinkets alongside masks and grapes hangs over her door. A density of plants lines the sides of the house and out of the frame of the image.

Photos of Rowe standing outside the Playhouse show a sovereign artist beside her greatest creation. She transformed her entire property into a living artwork. For Rowe, her creativity was a divine responsibility. God gave her the gift—her job was to use everything she had. Chewing gum. Bottle caps. Scraps of fabric. Junk mail. Nothing was wasted; everything was worthy. Entirely self-made, self-curated, and fiercely independent, The Playhouse was her crown jewel. It existed outside the gaze of institutional approval, beyond the rules of white box galleries and hierarchical taste. It was a radical offering: art that was of the people, for the people, in the most literal sense. A space where artmaking and art-viewing became inseparable from life itself. Around 400 visitors went every year, leaving recycled items for Rowe to adorn the Playhouse with after they left. I saw firsthand how many people were impacted by Rowe’s Playhouse through her visitor sign-in book that is displayed. Thick, and full of names and comments from hundreds of visitors expressing excitement over their visit, The Playhouse gave her autonomy over her creative output.

Folk art refuses to be anything other than what it is: real, resourceful, and rooted. It resists pretense and emerges not from academic studios or elite mentorships, but from daily life, from necessity, from the soul. Folk art, especially in the hands of Black women like Rowe, becomes a counter-archive: documenting lives, dreams, and rituals that dominant histories overlook. It is a preservation tool for communities separated by race, class, and geography from institutional recordkeeping. In Rowe’s work, her art held onto the stories that weren’t considered “important” by the mainstream but were everything to those who lived them.

Nellie Mae Rowe’s legacy dares one to consider: what would art look like if the gatekeepers were removed? What stories would get told if Black women artists were allowed, like Rowe, to define the terms of their visibility, value, and voice? In a world that often measures worth through pedigree, price tags, and institutional approval, Rowe built something radically different—an artistic life rooted in intuition, faith, and unshakable self-trust.

In claiming her own creative sovereignty, Rowe dared to show what it looks like to be really free, not for a moment, but for a lifetime.

This perspective is evident in her famous, magically chaotic Playhouse, but it’s just as strongly declared in her simplest works. Take, for example, God is not Dead (1971). On a slab of corrugated cardboard, Rowe used crayon to draw her hand, outstretched in praise, purposefully colored a few shades darker than her actual skin tone, in a gold picture frame. On the right side of the piece, the words “God is not Dead” are written in her signature large, flamboyant, purple script. This image of her dark brown hand paired with her declaration of God’s presence serves as a testament to her faith, the beauty she saw in herself as a creation of God, and the beauty she sought out in the world.

Rowe found this beauty in unlikely places, transforming found object and humble materials—buttons, chewing gum wrappers, bits of fabric—into works of art. Her art turns the language of scarcity into one of abundance, refusing the false boundary between “craft” and “fine art.” Rowe didn’t wait for permission. She made space for herself and, in doing so, made space for others. Her art reminds one that validation can rise up from the ground, from the hands that create, from the stories told in secret and in plain sight. In claiming her own creative sovereignty, Rowe dared to show what it looks like to be really free, not for a moment, but for a lifetime.

[1] Rudd, J., & Thompson, K. (2017, November 22). The art of Nellie Mae Rowe. Afterlives of Slavery. https://afterlivesofslavery.wordpress.com/visual-art/the-art-of-nellie-mae-rowe/#:~:text=Unfortunately%2C%20Rowe’s%20work%20was%20not,tail%20end%20of%20her%20life.