Now it is time for me to rest and play.

Rest and play are not mutually exclusive, nor are they synonymous. But they can be at odds with one another or perfect bedfellows. For Nellie Mae Rowe—an artist who spent much of her early life using her hands for manual labor and much of her later life using her hands to create art—they were both at odds and perfect bedfellows.

The time that she spent drawing phantasmagoric scenes in crayon, fashioning creatures of her own conception with used chewing gum, and incessantly adorning her living space was a well-earned respite. But the period during which she was most artistically prolific was also a time of restlessness; Rowe made art as if her life depended on it. Indeed, she created art until she was no longer physically capable at the end of her life.

Nellie Mae Rowe’s work is on display at the High, in the first major exhibition of her art since The Art of Nellie Mae Rowe: Ninety-Nine and a Half Won’t Do began its tour at the American Folk Art Museum in 1999. Even the name of the turn-of-the-century exhibition, a reference to a song by Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Katie Bell Nubin, was a testament to Rowe’s tenacity and passion. In the impressive lineup on view in Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe are works from 1947, when Rowe was still doing domestic work, to 1982, when her success was skyrocketing and her time on Earth was nearing an end.

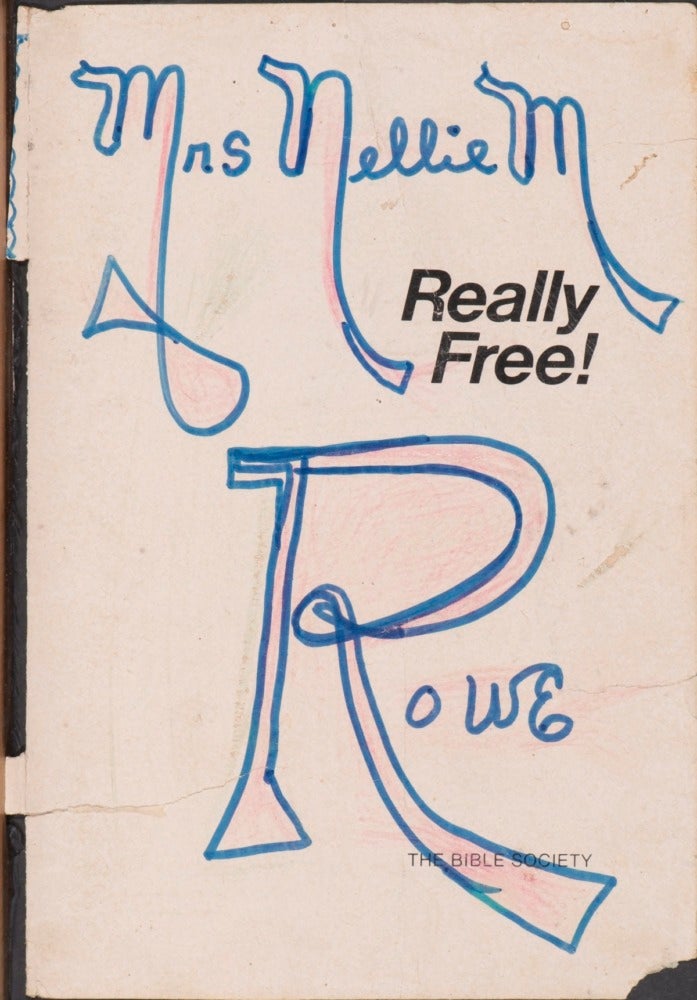

The show opens with the piece it’s named after: Untitled (Really Free!), the title page of a 1967 Bible Society pamphlet. On it, Rowe has inscribed her name in her signature fanciful way, with a flourish reminiscent of the bubble letters and crude cursive from my own childhood. I recall the odd enthusiasm my peers and I had for embellished letters as tweens—we made the dots over our i’s bulbous, found novel ways to make all the other letters fatter and more flamboyant, and embellished words with squiggles and 3-D effects. Nostalgia aside, I’m also fixated on the word “really” and how it could modify freedom, a concept already nebulous, fluid, difficult to grasp for a Black woman in the 1900s South. Here, did it mean truly or genuinely, free in a way that could not be disputed? Or did it mean extremely free, a freedom that surpassed all expectations? Perhaps it was a message of affirmation in the face of internal and projected doubts, an assertion of liberation in a world that tried its best to convince her that freedom is not guaranteed or even attainable. Either way, Nellie Mae Rowe “followed her line,” on paper and in life, to a place where she was uncontained, and her dreams were made material.

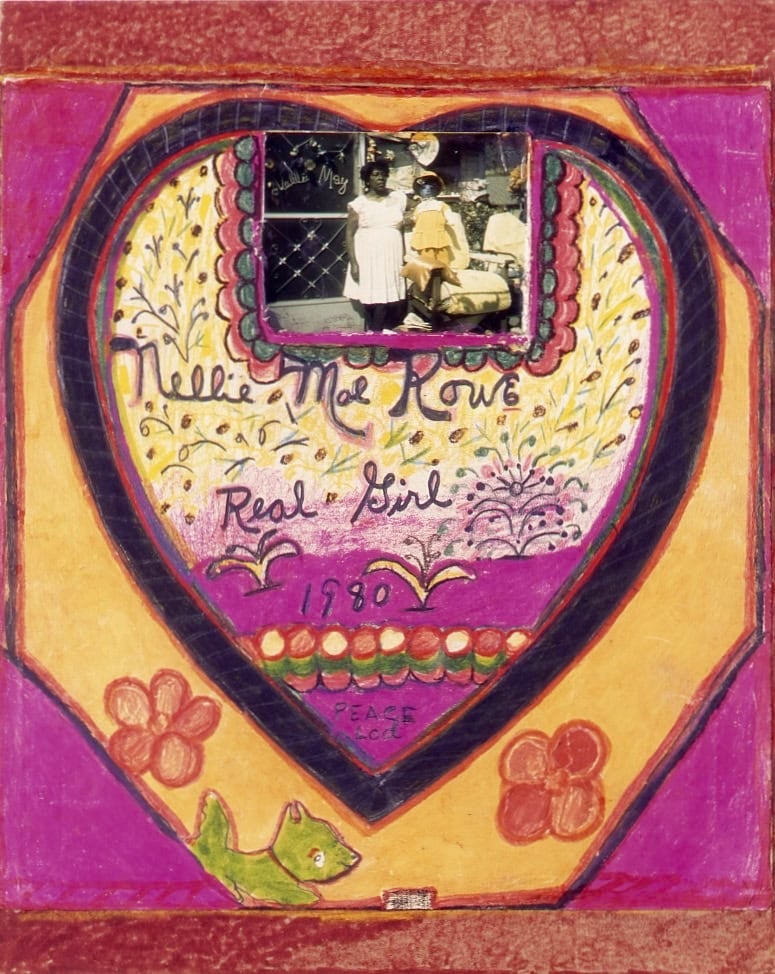

The abridged version of Rowe’s storied life is this: She was possibly born on July 4, 1900, and definitely born in Fayette County, Georgia. She worked in the fields and on the family farm as a child, when her interest in drawing and doll-making emerged but was forced to take a backseat to her domestic and agricultural responsibilities. She married Ben Wheat in a union that was likely less than fulfilling, moved to Vinings, and took Henry Rowe as her second husband after Wheat died. When Henry Rowe died in 1948, she worked in the homes of white families for a living and returned to her art. Beginning in the late 1960s, her artistic practice blossomed—she drew on materials that she had on hand, made sculptures, and decorated her home’s interior and exterior with chairs, Christmas ornaments, stuffed animals, photographs, and other knickknacks that attracted flocks of visitors interested in her peculiar brand of creativity. The art world at large also took notice of Nellie Mae Rowe’s work, and in 1978 gallerist Judith Alexander gave Rowe her first solo exhibition in Atlanta at the Alexander Gallery. The pair formed a bond, and Rowe spent the next four years churning out artwork, rising to stardom as a self-taught artist, and living in her Playhouse (the moniker she gave her home) on Paces Ferry Road.

The images that Rowe drew were often amorphous, changing from dog to human to butterfly to tree. Her lines were soft and free, tracing sensuous forms and mysterious stories that only she could tell. Sometimes her bold, bright shapes gave way to assertive phrases, like “this world is upside down,” or “God is love.” Occasionally words were misspelled, as in the eponymous artwork My house is Clean Enought to Be healty and it dirty Enought to Be happy, a saying she saw on a napkin at her niece’s home. She made works about voting, about the Atlanta child murders of 1979-1981, and about the wrestler Claude “Thunderbolt” Patterson. Ever present were themes of transformation, of gentrification, of sexuality, of legacy, of devotion, and of death.

Though Rowe’s drawings were chock-full of color and symbolism, she didn’t speak much on their meaning or what the shape-shifting creatures in them were meant to be. She didn’t need her work to be profound, she didn’t force it to be in conversation with anything, and she didn’t seem compelled to decode it for anyone. Notably, she did say in an interview with Judith Alexander, “I draw what is in my mind. I draw things you haven’t seen born into this world.” She knew she had an intellect and sight that others didn’t. She knew that she had a vision worth sharing with others. Of her chewing gum sculptures, she said that she wanted the gum to show what she “chewed up” herself. She didn’t want anybody else’s gum. Not only were her visions idiosyncratic, but they were also prophetic. Rowe understood the singularity and power of her creation, and she dared you to claim that you’d ever witnessed anything like it.

For Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe to arrive in this moment feels felicitous. Many people and organizations—like Judith Alexander, the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, and the American Folk Art Museum—have made an effort to preserve, promote, and exhibit Rowe’s work in the years after her death in 1982. The High itself has been steadfast about acquiring and showing her work over the last 40 years. And scholars and art institutions have long championed Rowe as an artist worthy of study and recognition, even as other Black artists were shut out of shows and struggled to gain renown. So, no, it’s no surprise that the High would revisit Rowe’s legacy in such a major way, framing her art as radical and her viewpoint as feminist.

What strikes me as apt is the opportunity the exhibition presents to engage with Rowe’s art and life at a time when Americans (and particularly Black Americans) are beginning to engage with the importance of rest, leisure, and dreaming in more dynamic and deliberate ways. Take the work of Tricia Hersey of The Nap Ministry, the wild popularity of Black joy as a concept, and the ways the global COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to recognize the toll of work and reprioritize our mental health. We are acknowledging rest as resistance, untying ourselves from the idea that we are machines made to be in constant states of production. We are acknowledging how vital recreation and relaxation are. We are mourning what Black folks lost in centuries of forced labor and stolen peace. We are prioritizing sleep and imagining what we can conjure if we dream. We are proclaiming the generative power of pausing. We are saying, “Now it is time for me to rest and play.”

After Rowe’s passing, her Playhouse was destroyed to make room for new development—a hotel now stands on the property. I grieve what we lost in her death and the death of the Playhouse, though the recreation of Rowe’s built environment and the clips from the forthcoming Opendox documentary on Rowe in Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe are immersive enough to alleviate some of my regret. Because there is little surviving audio and video of the artist, the documentary will feature animations of Rowe and scripted performances based on her quotes. Opendox commissioned artists to re-create Rowe’s Playhouse for the film, and this set, as well as scenes from the film, are on view in the exhibition. I cannot help but think of Moms Mabley, another extraordinary Black woman artist who has been on my mind lately, and how she achieved her most expansive moments of fame as she approached her life’s end. It’s not unusual for Black artists who do not directly address social issues or who operate outside of prescribed norms to find widespread success late in life or posthumously. Yet both Mabley and Rowe attained recognition that many other Black women artists in their fields never do. Rowe’s fame is a welcome anomaly. The fleeting, improbable nature of Rowe’s success is a paradox that I will have to live with.

“All my dolls, chewing gum sculptures, everything will be something to remember Nellie,” Rowe said. “If you will remember me, I will be glad and happy to know that people have something to remember me by when I have gone to rest.” Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe would, with little doubt, make Rowe glad and happy. It demonstrates how Rowe left her mark on the people who visited her home, the people who viewed her art, and the people who witnessed her unfolding into the artist she always wanted to be. She worked, she rested, and she played. What more could you ask of a person?

Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe is on view at the High Museum of Art thru January 9.