Imagine a garden. Imagine overgrowth. Imagine tangles and tendrils and dirt sewn together. Hold a flower in your mind. I conjure morning glories: vines overtaking the surrounding foliage in favor of their diurnal blooms. Some of the flowers open at sunrise—others reveal themselves at dusk. Seeds of the convolvulaceae, the family name of these unfurling petals, are also notoriously hallucinogenic in large quantities. These perennial climbers bore visions to spiritual leaders in ancient Mesoamerican cultures, inducing new planes of reality from their twisting greenery.[1] Morning glories are multipurpose: healers, supplanters, and sites for allusion.[2] Gleaning from these floral strategists, fiber artist Aaron McIntosh has cultivated a visionary practice rooted in such botanical thinking.

Imagine a garden. Imagine overgrowth. Imagine tangles and tendrils and dirt sewn together. Hold a flower in your mind.

In a convergence of textile innovation and tradition, McIntosh, a queer fourth-generation quiltmaker, brings the undergrowth into his fiber practice. Using the quilt as a departure point, McIntosh transfigures textiles into sculptural forms to relay queer narratives often silenced in Southern communities. Using both wild and domesticated foliage, McIntosh honors and reinvents the legacies of harm and care grown in queer communities. Dual themes of invasion and cultivation are embedded in the artist’s piecework, recast as symbiotic forces in the germination of queer ecosystems.

At the center of McIntosh’s practice are two works, Hot House/Maison Chaude (2020-Present) and Invasive: Queer Kudzu (2015-Present). Notions of tilling and sowing, planting and pollinating, populate the aesthetic and social components of both works. Hot House/Maison Chaude captures the careful cultivation of a greenhouse, while Queer Kudzu encapsulates the verdant growth of a weed: sprouting fiercely of its own volition, often outside the parameters of cultivation. Each project illustrates and subverts the parallel invasion/cultivation of and by queer communities in the Southeast and beyond.

Invasive: Queer Kudzu

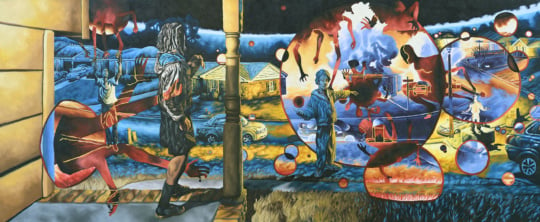

McIntosh’s expansive botanical Queer Kudzu project began in 2013 with the exhibition Untended, a moniker used to reference neglected gardens “and the surprising, perhaps unwanted growth that occurs when nature is unmanaged, allowed to freely form itself.”[3] On view in this exhibition were McIntosh’s series of Weeds: patchwork plants fabricated out of fragments from romance novels, gay erotica, and vintage fabrics. McIntosh’s Weeds speaks to both the ‘unwantedness’ of weeds in a landscape, as well as the artist’s “own anxious efflorescence as a queer person in a tradition-steeped culture.”[4] The impulse to archive and explore queer life from the works exhibited in Untended blossomed into the multi-pronged social practice project Invasive: Queer Kudzu. McIntosh describes Queer Kudzu as a “project for Southern Queers and their allies, which challenges the negative characterization of invasive species and uses queer kudzu as a demonstrative tool of visibility, strength and tenacity in the face of assumed unwantedness.”[5]

Image courtesy the artist and 1708 Gallery. Photograph by David Hale.

McIntosh invites participants to pick a fabric kudzu leaf and illustrate or write a queer story on the leaf (i.e. a coming out story, a memorial to a LGBTQ2S+ friend or historical figure, an ally’s message of support). The artist then quilts the individual leaves and pieces them together to form vines. Each vine is a gathering of leaves solely from the city where each iteration of the project takes place—thus, each vine is tethered to its place of origin even as the collective body of Queer Kudzu travels across the country. Since its inception, Queer Kudzu has grown into many forms.

Image courtesy the artist and 1708 Gallery. Photograph by Terry Brown.

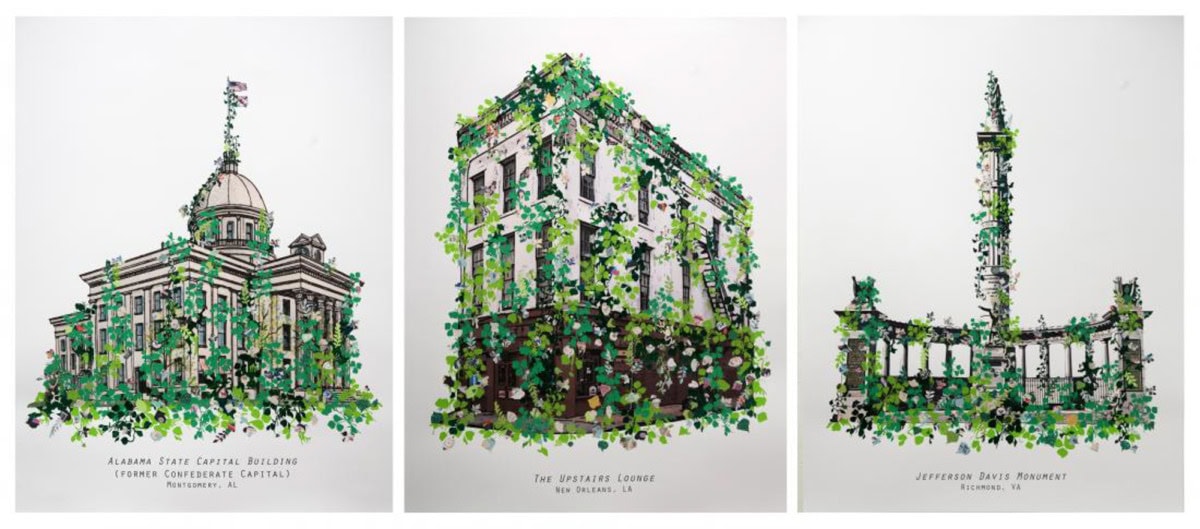

Most recently, the kudzu leaves took over Richmond, VA’s 1708 Gallery in an imagined demolition of the Jefferson Davis monument.[6] This installation was part of a larger Queer Kudzu offshoot titled From Poor Soil: We Will Overtake Your Monuments. In watercolor drawings, McIntosh imagines kudzu overgrowth suffocating Confederate monuments (such as the Jefferson Davis monument) and sites where inhumane legislation has come to pass (i.e. the Alabama State Capitol building). The Richmond installation of Queer Kudzu was host to events ranging from quilting bees to daytime dance parties. From this imagined destruction, McIntosh and participants envisioned a new growth for the communities that the sites, such as the Davis monument, had harmed. Interestingly, the Jefferson Davis monument was pushed from its pedestal by protesters and removed from the site with supervision from local police a year after this imagined destruction within the galleries.[7]

Monuments, 2019; collage on archival inkjet print. Image courtesy the artist and 1708 Gallery.

Hot House, Maison Chaude

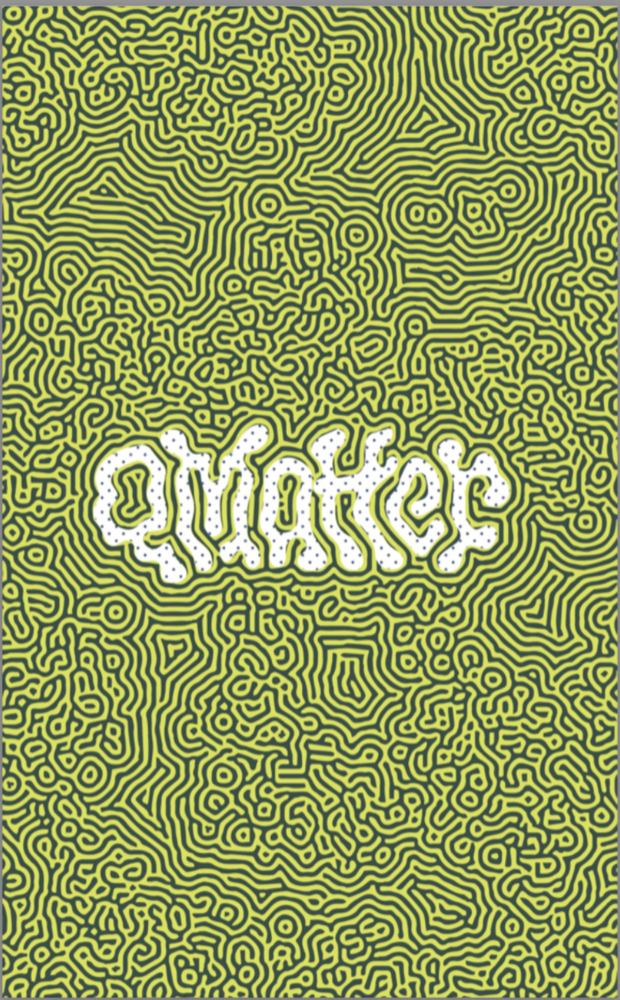

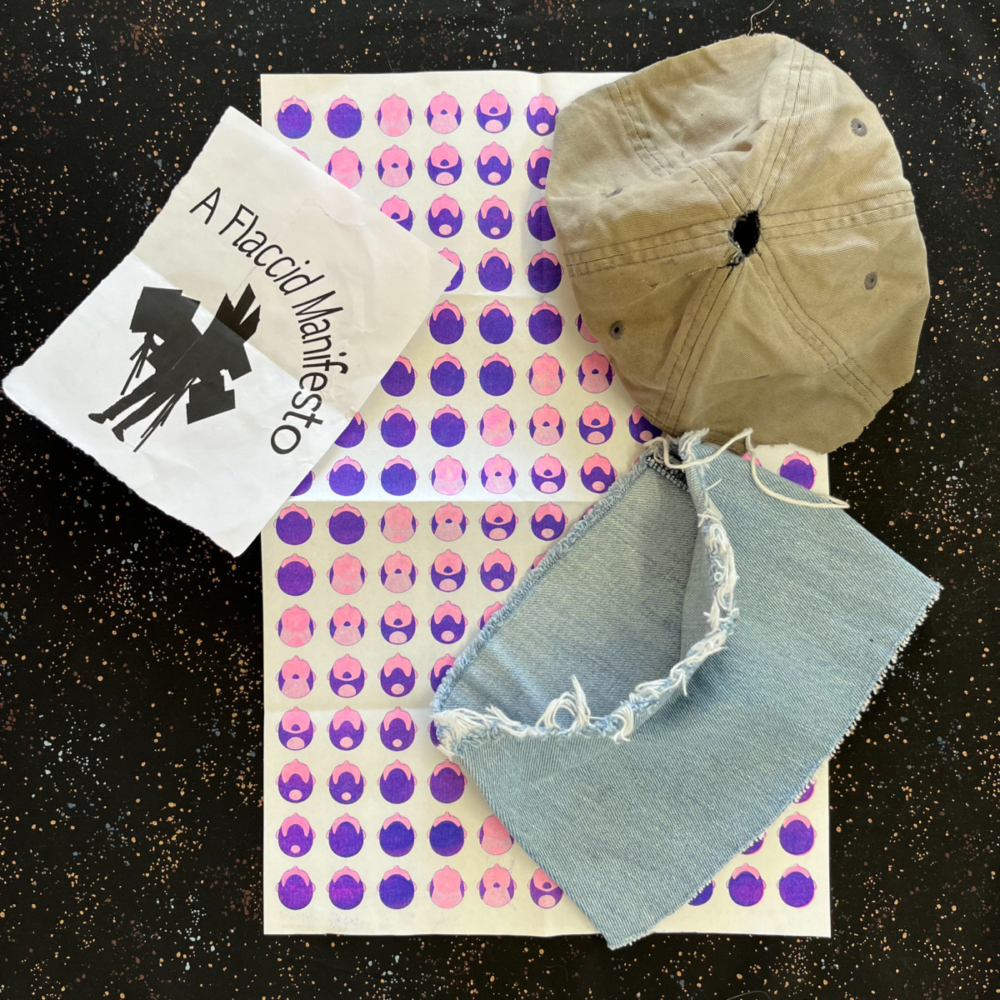

McIntosh continues to till queer life and kin to cultivate a new fertile ground. His latest project, Hot House/Maison Chaude, is a collection of several ongoing activities originating with an invitation. McIntosh sent a zine to LGBTQ2S+ folks and invited them to contribute qMatter (queer matter, which has come to include books, underwear, love letters, and other biodegradable materials). Since receiving this qMatter, McIntosh has pulped the items and transformed them into paper. These parchment fragments are then added to a compost pile. McIntosh imagines new nourishment and growth emerging from the decaying organic matter, mirroring the reciprocity seen through generations of queer communities: relinquishing what touched one generation so that something may grow for the next.

Another branch of McIntosh’s Hot House/Maison Chaude is underway at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Northern Virginia, where McIntosh is an artist-in-residence. McIntosh is “invading” the Foundation’s archives to destabilize the botanical language and redefine what is considered natural. In addition to the collected qMatter, McIntosh is fabricating queer herbals: illustrations of plants intended for queer healing. Perhaps a plant could grow a body part for a trans* person. A flower might act as a salve for a broken heart; a leaf might be the missing ingredient for a love potion powerful enough to halt hate. McIntosh envisions that the compost and queer herbals will exist alongside an actual greenhouse that can host queer dance parties, teach-ins, or a garden. Each of these acts—from the creation of compost from qMatter, through queer herbals, to the greenhouse structure itself—coalesces towards a vibrant queer garden.

Planting

Imagine worms. Imagine their underground paths through the soil: vermis, a Latin root for worm. Vermicular patterns take their name from the worms that wind them. Their organic, labyrinth-like ornamentation mirrors the way worms wiggle through the dirt. Found in the backdrop of many textile designs, the vermicular pattern in McIntosh’s work winds its way back underground. Printed on the pulped memories accumulating in the Hot House/Maison Chaude compost pile are McIntosh’s own vermicular motifs. This process of decay births flowers, though it’s less binary than that: there is a reciprocity not immediately apparent to the untrained eye, taking place all around us.

In his fiber practice, McIntosh enacts this botanical vibrancy on a human scale. McIntosh’s cunning approaches take their lessons from nature: embedding artifacts of gay life into new vegetables, implanting new ideas of what “blanketing” (in textile or plant matter) can mean.[8] McIntosh’s invocation of botanical species as invasive, growing, and decaying organisms in his textile works yields generative language to describe a futurity for queer growth and healing.

[1] “Turbina,” Encyclopaedia Britannica (Encyclopaedia Britannica), accessed September 11, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/plant/Turbina#ref118427.

[2] In the 18th Century, a term for a queer lover was a “twilight friend,” alluding to someone who only bloomed into themselves at sunset. Additionally, more floral terms have been used to describe queer people and queer acts (i.e. pansy, lavender menace, Sappho’s violets, Oscar Wilde’s green carnations).

[3] Aaron McIntosh, “These Woods,” Aaron McIntosh, accessed September 11, 2022, https://aaronmcintosh.com/section/378177-These-Woods.html.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Aaron McIntosh, “About,” Invasive Queer Kudzu, accessed September 11, 2022, https://invasivequeerkudzu.com/About.

[6] “Aaron McIntosh: Invasive Queer Kudzu” 1708 Gallery, accessed September 11, 2022, https://www.1708gallery.org/exhibitions/exhibition-detail.php?id=100.

[7] Mark Katkov, “Protesters Topple Jefferson Davis Statue in Richmond, VA,” NPR (NPR, June 11, 2020), https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/06/11/874565394/protesters-topple-jefferson-davis-statue-in-richmond-va.

[8] “Blanketing” conjures the action or image of completely covering with a thick layer. Here, that thick layer easily refers to both textile (i.e. the gallery was blanketed in the quilted leaves) and plant growth (i.e. the landscape was blanketed in ivy.

Learn more about Invasive Queer Kudzu.

This essay is part of our yearlong series Invasive Species.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2022 here.