Pastiche Lumumba, an Atlanta-based artist, curator, and cofounder, in 2013, of the LOW Museum. He is interested in contexts that shift between the high brow and low brow, as mediated through commodity and Internet cultures. His own multidisciplinary work examines the element of context and its effect on subjective experience. Being both an art practitioner and curator, I was curious to dialogue with him about how he conceptualizes his role in the production and dissemination of visual art.

Even though we live close enough to bike to each other’s residence, I decided we should exchange emails—a decision representative of Lumumba’s artistic and curatorial work, perhaps.

Meredith Kooi: I’m interested in how you position yourself as artist/curator/cultural producer. You have your own solo work and then you have the LOW Museum. In a way, it seems that some of the themes/concerns are shared between your work and the exhibitions/programming. Maybe that’s obvious since you are one and the same person involved in both. However, I’m curious about the internal dialogue you have and, with your collaborators at Low, about the work you make and the work of others that you present. What are the major concerns you address in your work? What are your major interests for LOW? What kinds of work are you committed to showing?

Pastiche Lumumba: I believe in vertical integration. It is essential that we as artists are able to embody the roles of curator, critic, collector, etc., in order to efficiently move through our careers. My solo work and my programming/curating at the LOW Museum are both concerned with the fluidity of context. I would like people to critically analyze the themes of my work/exhibitions within the fine art context as well as have that analysis resonate beyond the gallery architecture. I’ve been privileged enough to work with some artists who have expanded my practical vocabulary. Curating the work of others leaves me with more considerations about my own work. I get to compile the methods of various artists into one practice.

My LOW Museum collaborators and I are mainly striving to create engaging experiences that we ourselves would want to go to and ultimately live in. In that way, politics and representation play a large role in the decision process. It is important that we show work that inclusively explores contemporary issues in a professional yet accessible fashion. I want the LOW Museum to bridge the gap between the house show crowd and the museum crowd.

MK: Can you expand a bit on what you mean by “fluidity of context”? What are the ways in which the work shifts outside the, as you say, “fine art context”? Is this a question of audience and how meaning is interpreted/generated differently between audiences? Or, is this an ontological situation whereby the meaning itself changes with different context? Or, are these two questions the same? Can you talk through a work of yours that you feel exemplifies this?

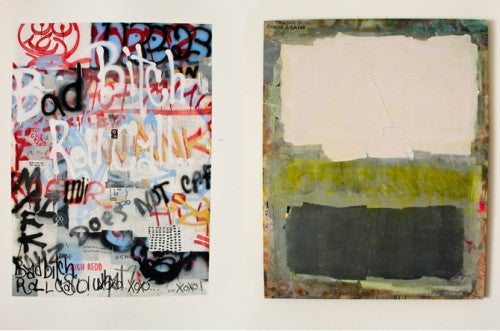

PL: The white wall gallery environment is attached to a set of disciplined historical and aesthetic conditions. An example would be my piece A Painting, which is a canvas that was spray painted by various individuals and then painted over (“buffed”) like graffiti on public walls. Within an art environment, it is preceded by its visual reference to Mark Rothko’s multiform paintings. The same painting presented on the street might read as a graffiti buffing and possibly be subject to more graffiti. The viewer’s discipline informs their interpretation and interaction. Context dictates what is even subject to interpretation. My painting within an art gallery context invites the viewer to meditate on the aesthetic quality of graffiti buffings. It is my aim for this consideration to resonate beyond the gallery walls so the viewer thinks about Rothko when they see graffiti buffings and vice versa.

MK: Let’s talk further about context through the phenomenon of site, which you also describe in your statement for A Painting, and also about how you define graffiti. Particularly since you’re discussing the ways in which it enters the gallery, it might be appropriate to parse through the particularities of graffiti writing and what we could also call street art. We could consider here Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Banksy, Shepard Fairey, Margaret Kilgallen, Pepon Osorio, etc., etc.—the infamous Exit Through the Gift Shop. Then, we’d have to consider other painted public art (i.e., murals), which may lead us from the Living Walls Project here but back to the politically charged work of Diego Rivera. Or, are we talking the culture of the hip hop documentary Style Wars and the online game Bomb It? Or, gang taggings?

Is this about the commodification of the public? How would you go about “appreciat[ing] graffiti’s natural site specificity?” What of Free Art Fridays?

Then, there’s the question of recent painting that almost mimics graffiti and the buffing of—some of which, including Oscar Murillo, is described in Jerry Saltz’s recent article in New York Magazine, “Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?”

Considering buffing is done with one color, generally brown, where does Mark Rothko fit in here? Why would you want the gallery-goer to consider Rothko when witnessing buffings on the street? Are you saying that this is necessarily a good thing? What are the stakes here?

PL: I’m defining graffiti as the unsolicited, necessarily anonymous writing and painting on public and private property. While they both may be unsolicited, the distinction between graffiti and street art is that street art has a known entity attached to it whereas graffiti is anonymous. This is a very important distinction because it dictates public interaction with the piece. In its first years, Living Walls did not get their walls approved and thus did not have to answer to anyone. Now that there is an entity attached to those walls, communities can point to the organization and hold them accountable for the content and possibly the removal of said walls. The problem is that the people who speak “for the community” are a powerful minority who generally have a legislative agenda. It has been widely reported from the artists and volunteers who painted the disputed murals that many actual community members did not object to the murals at all. If the person who spearheaded the campaign to get the city to remove the mural could have removed it themselves, it likely would not have happened. Graffiti largely has a detached interaction where people see it, but don’t think they are part of it because it seems that no one is responsible. It is seen as an anonymous nuisance that the public has power to remove only through the government.

The example of Banksy’s New York residency late last year comes to mind. People in the community personally painted over some of the pieces, some people preserved them, some were confiscated by the police, and others were cut out of the walls by art dealers. This is the kind of agentic interaction that doesn’t happen with graffiti by nonfamous artists. I feel as though that is a cultural deficit, so I want people to think about the gallery when they see a painted-over piece by an anonymous graffiti artist. I want this comparison to extend to Rothko, so that we can have an equalized conversation about aesthetics separate from the cult of the artist. I want to raise doubt about whether or not there even really is a difference between Rothko, Murillo, and the Atlanta Graffiti Task Force. If there isn’t, then I hope we can have meaningful aesthetic experiences while riding the train to work or walking through the Moreland tunnel.

I appreciate graffiti as it exists everywhere, but mostly in bathrooms, as seen from the train, and in abandoned buildings. There is something to be said about the locations in which graffiti exists that is lost in the gallery setting.

As for Free Art Fridays, it is a wonderful way to spread one’s art without the negative connotations of vandalism, crime, etc., but it still becomes not public as soon as someone finds it and takes it home. It falls back into the private commodity realm.

MK: It seems that this is also related to the ways in which we surf the net, scroll through Tumblr feeds, and assemble a multitude of images—something that you also address in your work. I guess we could almost talk about the commons in relation to both—however, the street and the Net, though they might appear commonly shared, are in fact not.

PL: We are constantly bombarded with images on the Internet and IRL [in real life]. The reading of such information is becoming increasingly nuanced because so much of it is out of context. Art, advertising, trolling, vandalism, and memes are sometimes indistinguishable from each other. It depends mainly on where we get the information from, so while the spaces are shared, our feed on the Net or our route IRL makes the information tailored to our individual experience. This is where the free sandbox of the Internet becomes narrowcast while maintaining the illusion of openness.

MK: What does that mean for you, then, as a curator, particularly one who is interested in showing work that invests/investigates netart and other forms of new media? Cara Mayuski’s show “Area Moments” is a good example of this because that work was thinking about the encounter between the digital and IRL. What are the challenges you come across in curating and presenting this kind of work? We’ve briefly talked about Brad Troemel and his project The Jogging, so it brings to mind the problem of what happens when “physical” “products” are created from their virtual counterparts (i.e., Troemel’s Etsy shop discussed in the Art in America article “Young Incorporated Artists”).

What are some exemplary models? How do you see LOW moving forward?

PL: It means that authenticity and purity of intention are all the more important. We see images and have to wonder what their intentions are. It is important that the author is aware of the multitude of readings and so works that much harder to create an unmistakable product. The romantic notions of modern era artistic production being unique, personal, and pure still apply in our digital landscape, but they do not manifest in the same way. Appropriation is much more transparent now, but it is also not as much of a detractor from purity. Unique objects are scarce, but collections of similar objects become objects themselves: artist as curator. The “Young Incorporated Artists” article makes this shift in sensibility very clear in the case of The Jogging where one artist’s output is subsumed into their curation of like objects. Their insincerity, however, is very apparent because they don’t have the pressure to make something that is (IRL) real. We tend to think of the internet as a cold, anonymous environment where nobody actually cares about things, but that is very far from the truth. That’s why I feel it is imperative to show work that engages the community both IRL and online. As artists, we must adapt to the current possibilities while constantly pushing those same boundaries.

For my curatorial practice it means skirting a fine line between maintaining an accessibly traditional gallery infrastructure and veritably representing elements of contrasting environments like the street, the home, and the internet. The main challenge is in presentation and preservation. For our upcoming Lowennial, the aesthetic is borrowed from design and photography-based tumblrs that frequently use physically impossible photoshop elements and ephemeral objects like fruit. I want to present these objects as one would see them online but certain conditions, like gravity and 3D space present logistical challenges. For our [July 28] LOWennial, the aesthetic [was] borrowed from design and photography-based Tumblrs that frequently use physically impossible Photoshop elements and ephemeral objects like fruit. I want to present these objects as one would see them online, but certain conditions, like gravity and 3D space, present logistical challenges.

Alessandra Hoshor comes to mind when I think of artists whose work brings the digital environment IRL but I mostly think of retail design. The com in .com stands for commercial and much of the internet is commerce and advertisement. I think that we are headed towards art presentations that look increasingly like storefronts based on digital stores. The LOW Museum will continue to narrow the gap between traditional fine art and the presentation of commodity culture.

Meredith Kooi is the editor of Radius, an experimental radio broadcast platform based in Chicago. She is currently a PhD student in the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts at Emory University, a performance and visual artist, and a monthly contributor to Bad At Sports.