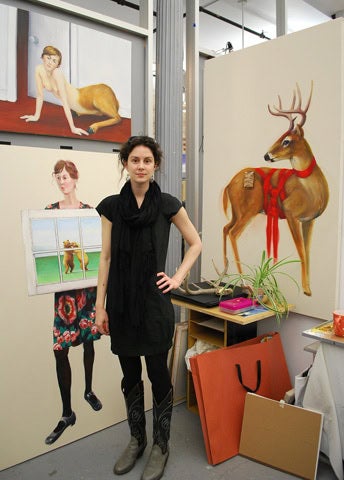

Born in Oklahoma and educated at the Atlanta College of Art, Loretta Mae Hirsch has traveled the world for her career, in pursuit of love, and to discover an exotic color she’d never seen before. A recent graduate from the MFA program at the New York Academy of Art, Hirsch (her name means deer in German) paints intensely personal images that transform the familiar into the uncanny. BURNAWAY is proudly hosting Hirsch this Sunday, October 16, 2-5PM, for an intimate luncheon fundraiser and artist talk where she will share her works and the stories behind them.

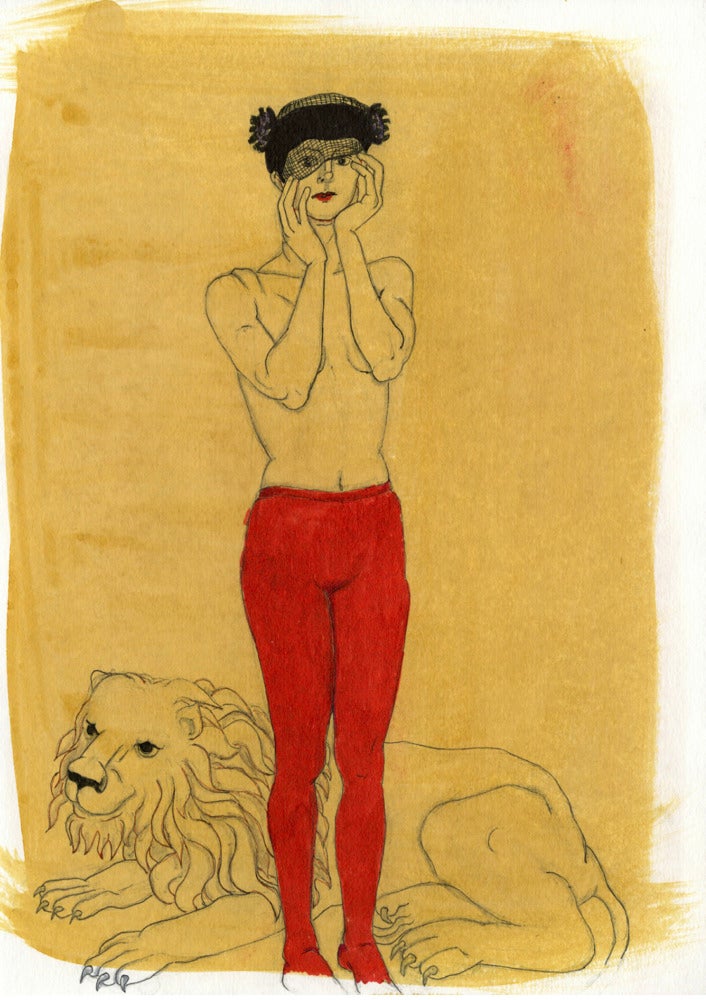

Her recent solo exhibition, Infinite Desire, at the Hionas Gallery included a series of oils on canvas that depict the artist increasingly bound by ribbons. Inspired by Slavoj Žižek‘s book, The Plague of Fantasies, these self-portraits present a meditation on how one surpasses the simple objectification of desire. Since I will be serving as moderator for Sunday’s artist talk, I spoke with Hirsch by phone to prepare some notes, and I found her to be an engaging personality with a slight lilt to her voice. Our conversation follows.

Paul Boshears: How was your transition from Atlanta to New York? What led to that?

Loretta Mae Hirsch: [Laughs] It’s not so simple, really. I left Atlanta a number of times, actually.

I left Atlanta to find the color yellow. I was in Glasgow, attending classes there, and I made a trip to Barcelona. On the bus to Madrid, I saw this color yellow that I’d never seen before, and, for a painter, that’s really peculiar—that I hadn’t experienced that visual moment. So I promised myself that I would one day go back and find that yellow. It took years, but I saved my money. I had this traumatic health problem, so I decided to take myself, for my birthday, to find that yellow. It was the most magical experience. The flower [that blooms in this yellow] is a wild orchid that grows in the mountains of Montserrat, a religious mountain. I fell in love and stayed.

PB: You were born in Oklahoma, but do you ever feel Glaswegian?

LMH: Well, no. I did learn about my name in Glasgow, and I do miss Glasgow. I also began drawing in Glasgow. It was a very magical moment for me, there.

PB: What compelled you to start drawing there?

LMH: It’s a silly story, really. Prior to painting on unprimed surfaces, I had a problem knowing when to be finished with a painting. So I would work on the same painting for months and months, or even a year. I just couldn’t figure it out. When I moved to Glasgow, this problem had been driving me mad, and I began having these nightmares. They were so horrible. It’s really silly, but the first one was the only one that was different from the others. I developed insomnia.

The nightmares were ridiculous. In the first one, I got a phone call, and the person on the other end said, “Loretta, do you know who this is?” And I said, “No.” And he said, “Well, you’re going to remember me now.” And I said, “Excuse me?” And he replies, “This is Jack the Ripper. If you don’t finish your painting I am going to keep calling you.”

And so every single night I had the same dream where he would call and ask me, “Do you know who this is?” I would reply, “Yes.” Then he would say, “I’m going to come and get you.” Every single night. I couldn’t sleep at all.

So my mom sent me this giant box of markers, and I started drawing the things that I would see in the night out my window, or when I would take walks around Glasgow.

Eventually, I sat myself down, and I had a dialogue about the process of painting itself. I’d ask myself, “Do I need to build the stretcher?” Yes, I need to build the stretcher because I need to stretch the fabric over this, and I do like the tension. “Do I prime my canvas?” I thought about it, and I couldn’t think of why I needed to prime the canvas. I do it because it’s something someone told me to do. It’s not something I enjoy doing a whole lot, so I just took kept the primer out. From that moment, I knew how to finish the paintings. Jack the Ripper never called me again.

PB: That is wild! What a great story. Shifting gears, what is it about the tense fabric that you like?

LMH: I like that it’s supple: that the mark-making isn’t totally controlled. If you paint on a primed canvas, you have complete control over it, and you can put paint on either edge and fill in the holes. If you paint on something that is absorbent, however, you’re limited. If you put the brush down, all the paintings are alive: the oil and the pigment separate, and this halo starts to build around the images. They’re continually changing, even when I am not painting on them.

PB: It sounds like a process of discovery, then.

LMH: Yes, and they’re alive. I like that idea very much. They’re mortal; they won’t live forever. Unless they’re put into some conservation environment. But not in my lifetime. They will certainly outlive me.

PB: Your exhibit at Hionas Gallery, Infinite of Desire, references the philosopher Slavoj Žižek, and it seems to have a significant psychological gesture ….

LMH: I read Žižek’s Plague of Fanstasies, and that series of images you referred to, of the women being bound, that series is a response to a line in his book, “How can the infinite of desire be placed onto a finite object?” The moment I read that sentence, I had this vision, and that’s what lead to those images in that series.

I was going through a difficult time, and that quote really spoke to me then. At that moment, I was being desired by a man. His vision of who I was, and what I was, just wasn’t at all how I felt myself to be. So I became this object that was being contained by this desire that was creating a new identity, but none of that identity was mine. And, so, in simple poetic terms, the ribbon symbolizes that desire. It can take on any shape, but it kept on, more and more, binding that woman. In the end, I didn’t want that woman to be just that object, so the last two paintings in that series are inverted. We have this finite ribbon and the shape of a woman, but she is formless and infinite.

PB: I’ve seen your paintings described as feminist. Does that term hold much for you in terms of creating your images?

LMH: I’d certainly say that I am a feminist. I am not at all for the repression of women. That said, I don’t know that I am painting from a Feminist perspective per se. I am much more of a Romantic. My studio has absolutely no windows. I control all of the light in the studio. It’s like when people go to the cinema, and they are swept into this other world. But then they exit and are spilled onto the city streets with the lights and the noises. For me, I like to build these universes, and my sense of time is skewed. I can stay there for who knows how long, and I create this environment. When I leave—my studio is in China Town—I emerge into this chaos. I love it.