Gregory Green is internationally recognized for his challenging work and the numerous controversies it has spawned in the U.S. and Europe. Since the mid-1980s, he has created artworks and performances exploring systems of control and the evolution of individual and collective empowerment. Green’s work considers the use of violence, alternatives to violence, and the accessibility of information and technology as vehicles for social and political change. Referencing historical precedents and eerily anticipating various historical events like the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the Arab Spring, Green’s provocative works expand the parameters of art and activism, culture and social commentary.

I recently was able to chat with Green about his work and his amazing career, which involves the Young British Artist movement, a heightened awareness of terrorism in America, and the shaping of future artists as a professor of sculpture at University of South Florida. His show “Gregory Green: a History of Dissent, 1979-2014” was recently on view at Gallery Protocol in Gainesville, Florida.

Budd Dees: Could you tell me a little bit about your show at Gallery Protocol? I’m curious about your choices and how you thought about the pieces in a space together.

Gregory Green: I’ve reached a state in my life and career where I’m starting to look back at everything I’ve done, and having on certain levels, both cognitive and intuitive, a better understanding of what I’ve been doing all my life. Basically, I wanted to do a test of another retrospective; I’ve had a couple of small retrospectives in Europe that focused on the post-’90s work.

BD: So the work in this show dates back to 1979?

GG: Right. I realized that I‘ve been dealing with the same sorts of issues but in two different ways since undergraduate school. After my last one-person show in New York, Joe Jacobs, who is an editor for the Janson History of Art textbook, wanted to do an article, but we never got it done. We spent a lot of time talking about the overall history of my work. He’s considering me for a new edition, because he thinks my work has been important and also relevant to what’s been going on in the world in the last 30 years, while I’ve been working. This Protocol show gave me the opportunity to test that.

BD: What provoked your interest in weapons or in this subject matter? I was thinking about those boys in school who get in trouble for drawing knives and guns instead of paying attention in class. Was that you as a child?

GG: Oh no! As a child, I was a very conscientious student and worked way too hard. Actually, as a child I had ulcers because I was always trying to overachieve. My dad was in the Air Force, so because of that people think, “oh, well, that’s why you do this work.” But in reality, I lived in Europe in the ’60s and ’70s. At that point, we were in the middle of the Cold War and Europeans were incredibly politically conscious, so I was exposed to a lot of things. I was basically living in the battleground of the Cold War and where the Third World War would start. I was a bit of a precocious kid and was aware of all these factors. In my teenage years, I was sure that I probably wouldn’t live past the year 2000, that the world would go up in flames in the Third World War apocalypse between the Soviet Union and the United States. I was this person who felt trapped between the two sides. I had a sense of helplessness, a lack of a sense of a future, and also most of the Europeans at that time were radically opposed to authority.

So really, from the very beginning, all of my work has been about the individual’s relationship to a greater structure of power, particularly those that have control over us. My earlier work was about ways that people would respond to these situations. It focused on ways that fear was used to manipulate and control populations.

From 1979 until 1988-89, the work was really focused on the victim and myself as the victim, and how we’re victimized and controlled. In 1988, I had the unusual desire to build a pipe bomb. I didn’t know why, but I knew I wanted to do it in the studio. It wasn’t functional; like all of the works, it was mechanically complete but they don’t have any explosives. I think that piece sat in my studio for a year and a half. Then suddenly, it clicked in my brain that my relationship to the individual and any power structure … that I was tired of talking about being a victim. I wanted to talk about how we as citizens can stand up to those situations and alter and change our world to make it a better place. That’s what I’ve been exploring and really solidified in 1991.

BD: Yeah, some of the work felt very contemplative and then some of the work felt very aggressive. I was very bodily aware of your objects. “Don’t step on that thing over there, you could injure yourself.’

GG: There’s the sociopolitical issues I’m dealing with, but also I’m dealing with aesthetic issues as well. The whole idea of making a potentially functional bomb, putting it in the gallery, and calling it art and not telling the viewer whether you support or oppose the use of violence is totally messing with the expectations of the gallery-goer. So a lot that is trying to alter our expectations of the sanctity of the gallery space, the role and function of art within that environment, but also how the use of spectacle functions. Jeffrey Deitch [New York art dealer and former L.A. MOCA director] once called the work “conceptual terrorism,” which at first I was uncomfortable with, but then I realized he’d really nailed it. The saw blade pieces are truly dangerous. Nobody expects to walk into a gallery and face death. Although, I will say that I was heavily influenced by Chris Burden in my education.

BD: It’s very strange to think about your work in the gallery space, for sure, and it made me think that your studio wasn’t really a studio but maybe a van or a basement where you made bombs. How much do you get into the headspace of being a violent radical?

GG: Well, the worktable installations were originally meant to show the potential violence, but they quickly changed to consider the character that would be the bomber. If you look through all the material of the piece at Protocol called Work Table #10, what you end up with is a Christian militia character or a sovereign citizen person. Homeland Security recently said that the three biggest threats to the United States in terms of terrorism are, first, the sovereign citizens movement, second, al Qaeda, and, third, Christian militia. So according to the Department of Homeland Security, we are more dangerous to ourselves than the “Other.”

Along that line of thought, the film director John Waters commissioned a piece in 2000. I stayed in his house making the piece for three weeks. I had already decided that these pieces would be from a character, and I had to identify what they might be going after or what their issues might be. They’ve been both male and female. John was between movies and so he was around all the time. I told him, “I’m not sure who this person is living in your attic building bombs.” I went through a list of possibilities and one of them was a film terrorist, and he said, “No, no, no. You can’t do that. That’s my next movie.”

BD: Oh, Cecil B. Demented! Is that the film?

GG: Yes.

BD: Oh my god! I was talking about Patty Hearst [who appears in a few films by Waters, including Cecil B. Demented] to a friend when I was talking about your work! She’s just such an amazing example of what a terrorist isn’t supposed to be—and the idea that one can be totally reintegrated back into society and can become a film star.

GG: Well I grew up with terrorism as a part of my life. It was just the reality of that time in Europe, so I have a very different relationship with terrorism than most Americans.

BD: Yeah, I think that September 11 was the moment when terrorism became a part of my everyday life.

GG: Right. Well, first the Oklahoma City Bombing changed things, and then 9/11 totally changed everything.

BD: On another subject, you now teach at University of South Florida. I was wondering if you incorporate dissent in the classroom? I’m wondering how you approach that?

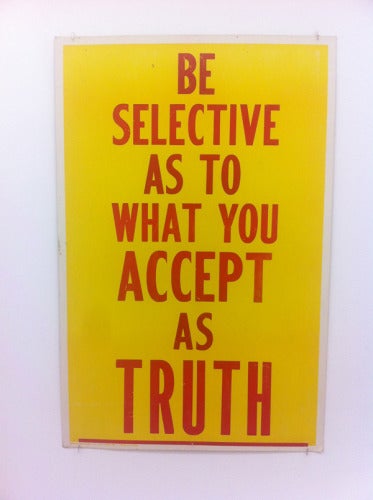

GG: I teach strategies of intervention and dissent, both in the aesthetic world and in the public world. There are specific projects that deal with these topics. The first assignment is about defining your mission. It’s called “the object of self.” Artists of any medium are really talking about themselves, their world, their experience of the world. The generation that I’m teaching are going to be the next generation of artists. The concept of dissent falls into that as well. You have to break the rules of now to shape the future.

Budd Dees is a maker working in real and virtual spaces as a sculptor, writer, and digital artist. He lives and works in Gainesville, Florida, where he teaches and creates. He loves cats, distrusts experts, and his boyfriend lets him sing the boy parts on the B-52s “Song for a Future Generation” (because he really does want to be “the nicest guy on Earth”).