Putting Your Artwork on Social Media

In today’s age of technology and the gig economy, sharing artwork on social media for self-promotion is commonplace. However, there are implications for artists and their intellectual property rights when they post their art on the Internet. Since artists aren’t about to stop posting their work on social media, what exactly are their intellectual property rights and how can they be safeguarded? In the event of copyright infringement, what’s the best course of action?

What rights does an artist have?

U.S. copyright laws protect visual artwork from unauthorized reproduction (copying) whether or not it has been registered with the U.S. Copyright Office. The right of reproduction includes the right to make and sell copies of a piece of art, to create derivative pieces (art based on a previous work), and to distribute copies or display publicly. Works that are protected by copyright and created on or after January 1, 1978 retain those protections until 70 years after the artist’s death.

For example, if an individual artist creates a painting, the artist has the exclusive right to make prints or duplicates of the painting for profit. Further, even if the artist sells the original work, the buyer can not create prints unless that privilege is given to the buyer by the artist in a written contract. Similar to when an author sells a book, when an artist sells their artwork they keep the reproduction rights unless it is specifically transferred in an agreement.

Considerations for Posting Art Online

So, what happens when your art goes on the Internet? Most of the time, a social media user agreed to the terms of service for that platform when their account was opened (you know, those boxes you’re required to click at the bottom of a page of small print).

Terms of service also protect the account holder from unauthorized use or reproduction of their work in other users’ posts even when the artist is credited. However, it is the artist-owner who bears the responsibility and cost of going after an infringer.

While this is all true in theory, the practical reality about terms of service is that most users do not read them and, even if they do, the terms may be difficult to understand. So even if the user has read the terms of service, they still might not understand that downloading a picture of an artist’s work and, say, printing it on a T-shirt, would be copyright infringement.

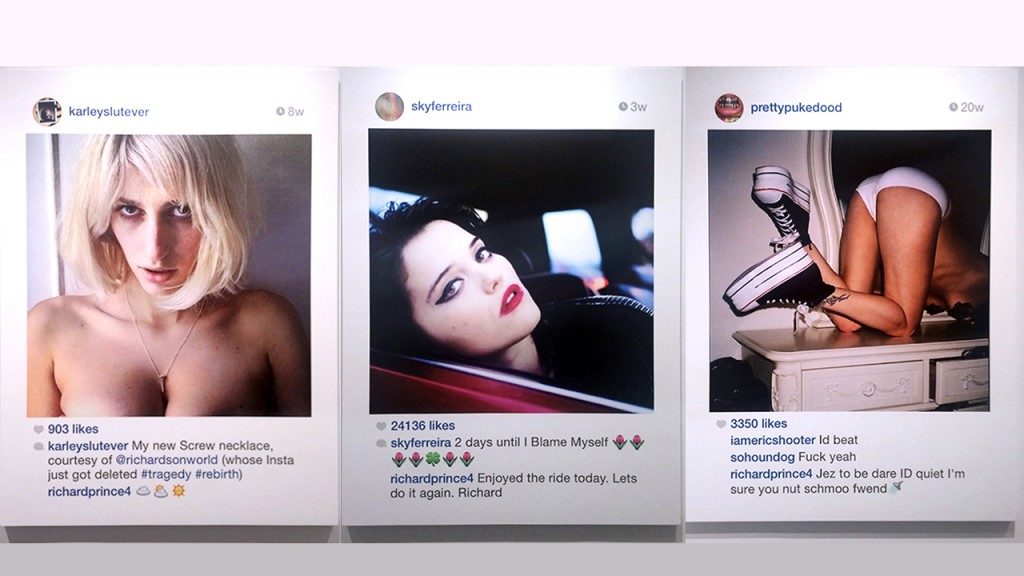

Social media users do, however, sign over their rights to platforms like Facebook and Instagram when they accept terms of service that include provisions that the hosting service has an “IP license” for the content that users post. In other words, they can use photographs for self-promotion without any compensation or additional permission from the owner. Further, some platforms may have the right to share the works with other entities although this is rarely exercised to avoid upsetting users.

How Artists Can Stop Infringement

As a preventative measure, prudent artists place a “notice” on their work and/or photographs of their work in order to let other users know the protected status of their visual art. For example, an artist might decide to place “© 2017 Artist” to eliminate any doubt about the ownership of a photograph or artwork and to emphasize that they have not consented to its use by others. The more prominent the placement on the website the higher the likelihood that someone will see it. Placing the copyright information over the image itself or in the post are two ways to make sure the image can’t be shared without the notice accompanying it.

Once an infringement occurs, and long before a suit is filed, the owner of copyrighted material should file a DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) complaint through the social media platform on which the infringement is occurring. Social media websites generally have these forms readily available within their “help” sections, but the forms can be most easily accessed by using a search engine with the website’s name and “DMCA complaint.”

So, if an artist posts a picture of their artwork on Facebook and someone downloads it and reuploads the picture as their own, the artist should go through Facebook’s “Reporting a Violation or Infringement of Your Rights” form to bring the infringement to the attention of the platform. After the form is submitted, the website is required to remove or disable the infringing content “expeditiously.” Although the infringing user has an opportunity to respond to the complaint with an explanation of why the content did not infringe the artist’s rights, most infringement issues within the context of social media stop after the first complaint is made.

In extreme cases, if an artist wants to stop an infringer through a lawsuit there are certain steps the artist must take. While it is not required to have registered the copyright to file an infringement claim, the copyright must be filed with the U.S. Copyright Office before filing a lawsuit. Furthermore, there are time limits that can affect the potential remedies that an artist may have.

One of these time limits has to do with statutory damages, which are the amounts of money that a copyright owner can receive in an infringement case. Under the Copyright Act, these awards are only available if the art was registered with the U.S. Copyright Office within three months of its creation. How many artists actually do that? Statutory damages can vary in amount, from $200 to $150,000, depending on the severity of the infringement and whether it was intentional.

If the work was not registered within three months of its creation, the artist can still sue, but the potential award is limited to the infringer’s profits and money that the artist lost as a result of the infringement. In contrast to awards for statutory damages, it’s hard to prove the infringer’s profits and the artist’s loss because they might not be obvious. Then there’s the reality that the cost of filing a lawsuit could be much higher than the payoff, and most artists aren’t willing or able to take action. If they do, the artist will need to demonstrate that they actually suffered a loss, which could mean hiring an expert to testify about the estimated damages, what was actual economic loss suffered which can be especially costly.

Luckily, registering copyright is straightforward and relatively inexpensive. Artists can register their works online for $35 per submission in most circumstances. While some artists might be reluctant to register every piece of art they make, especially within three months, they will have a much easier case than the artist who waits until infringement occurs to register their work.

This article is for general informational purposes only and is not meant to address any specific situation or provide legal advice.

Samuel P. Kovach-Orr is a law student at Rutgers University and wrote this while an extern with Georgia Lawyers for the Arts in Atlanta.