Bellevue emerges from the undulating hills of rural St. Ann. Guests slide onto humming golf carts lining the polo-field-turned-parking-lot. Fairway wheels bump along a dirt road, then spin up a hill dotted with wooden sculptures that meld with the tree canopy. At the top is an airy farm-shed filled with expansive sculptures beckoning guests into the world of PORTENT: The Potential for Something Magical to Happen (2024) by artist Laura Facey, curated by Melinda Brown.

Facey is a prominent Jamaican sculptor whose work spans almost fifty years. As she “strives to interpret the land around her and its histories,” she transforms fallen trees on her farm in historic Bellevue into sculptures that respond to these histories.[1] Facey’s aesthetics stand in the tradition of artist and educator Edna Manley, whose work emerged in the 1920s during Jamaica’s nascent nationalist movement as the colony sought to articulate its national identity. [2] O’Neil Lawrence, Chief Curator of the National Gallery of Jamaica, cites Manley’s work as a “touchstone” for Facey, who has expanded on Manley’s legacy with her move to abstraction and distinct use of textures and colour treatments.[3]

With over sixty pieces ranging from miniature to monumental, PORTENT is the result of two years of intense work and collaboration. Pieces such as Ode to Pig (2024) and Hear No Evil (2024) are forms unique to PORTENT, whereas sculptures such as One Way Arrow (2024) sprang from past exhibitions like PROPEL (2010).[4] Facey’s practice has evolved through internal exploration, monumental statements, reflections on colonial atrocities, and PORTENT marks a new chapter seeking “a healing alchemy for humanity and the earth” through self-aware meditation on her relationship to the land and nation-building.[5]

Facey’s positionality as a white presenting Jamaican woman and the period of her work addressing themes of enslavement head-on, might initially elicit feelings of discomfort, but there is more nuance than meets the eye.[6] Her father Maurice Facey purchased the Bellevue property with the Mount Plenty Great House in 1980, when there was significant economic instability and capital flight from Jamaica. [7] [8] Facey has been forthcoming about Bellevue’s ties to Jamaica’s history of enslavement: in the short film Paddlin’ Spirit (2016), she noted, “And here I am, living on a farm surrounded by walls that were made by [enslaved people].” [9] That PORTENT‘s setting should be Facey’s studio in Bellevue (an area formerly inhabited by enslavers, and enslaved Africans) means it is an exhibition borne out of Jamaica’s colonial legacies, but one that takes necessary initial steps towards addressing and repairing these histories.

Out of circumstantial messiness emerges beauty: raw, yet imperfect. Facey has a remarkable ability to hold contrasting themes in tension by fusing unexpected visual elements, using her creolized noblesse oblige to spur conversation around pressing global concerns, such as the climate crisis. For example, iridescent blue marbling resembling an oil spill meanders across Monolith (2023), and intricate floral carvings soften its phallic, missile-like structure. What emerges is a reflection on humanity’s dependence on natural resources, such as oil, and a reminder these resources ought to be stewarded with care, not for destructive capitalist whims.

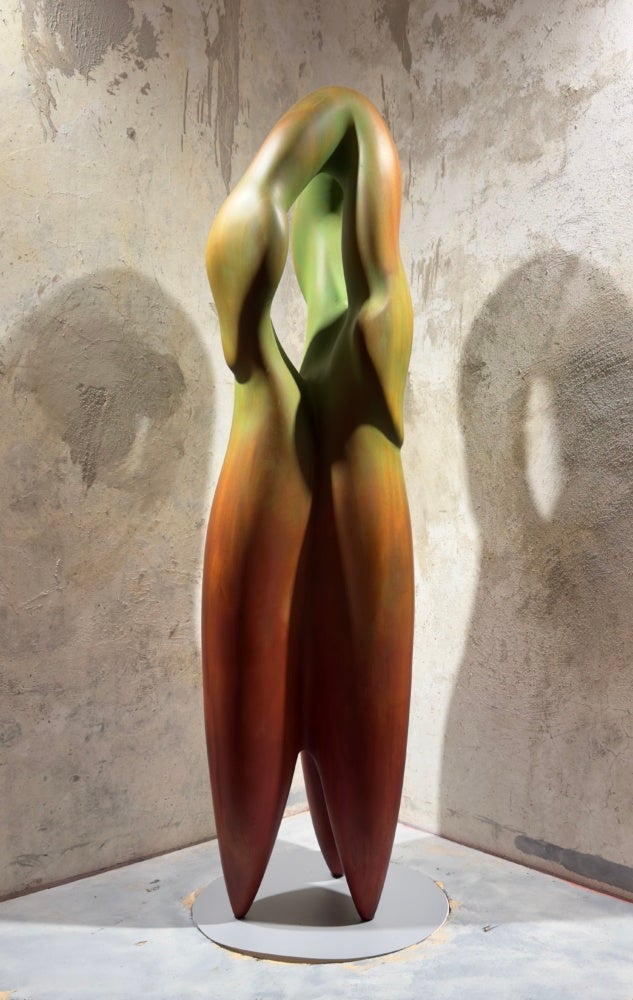

Sturdy structures like Monolith (2023) are contrasted with gentler sculptures like Ode to Pig (2024). Encased in an industrial alcove and set on a slow orbit, entrancing shadows dance on pig ears that metamorphose into a plant. Viewers get a glimpse into the “what if”: a utopian future where Jamaica is wholly independent. For Facey, Ode to Pig (2024) represents Jamaica being “done with […] the piggery of the English, the colonial,” where out of destruction the nation “blooms into a new plant, a new journey.”[10] As Jamaica celebrates sixty-one years of “independence,” Ode to Pig (2024) asks viewers: can the nation ever be done with its past?

Facey’s departure from narratives of enslavement surfaces the complexities of Caribbean art and race. She is simultaneously removed from direct connection to enslavement in a temporal sense, but also implicated in its legacies by grounding her practice in Bellevue and benefitting from Jamaica’s lingering pigmentocracy. White makers across the Caribbean have wrestled with whether to and how to speak about their relationship to enslavement. This is a particular kind of moral dilemma: a choice between being perceived as an outsider speaking to a predominantly Black culture and history, or being criticized for staying silent on the region’s traumatic past. In the Caribbean, white makers’ voices are a necessary supplementation to the nuanced histories of the region, so far as they are not taken as the authoritative voice, as was the criticism with Redemption Song (2003).

In 2003, Jamaica’s National Housing Trust (NHT) held a monument competition for Emancipation Park. This monument was to commemorate the emancipation of enslaved Africans in Jamaica. NHT’s judging panel selected Facey’s Redemption Song (2003) as the winner among sixteen anonymous entries, sparking public debate about how national ideals should be represented and by whom given the nation’s post-colonial struggle with racism, colorism, and class stratification.[11] More broadly, the rarity of monumental sculpture works like those in PORTENT in Jamaica raises the question: why can an artist like Facey accomplish this scale of work, and how can institutions support other sculptors lacking access to do the same? After twenty-five years of more autobiographical work, Redemption Song (2003) marked the beginning of Facey’s twenty-year-long reflection on themes of enslavement.[12]

As is the obligation of every Caribbean person, Facey must reckon with the hand she has been dealt and work to repair Jamaica’s fraught history and resulting present.

PORTENT embodies the messiness of the Caribbean post-colonial experience, one in which both beauty and destruction coexist, as seen through Facey’s relationship with the land and the critical role of her studio team. The core team comprises seven men from the surrounding community, who are likely descendants of enslaved people as part of the Jamaican majority: Kemar Davidson (Studio Foreman), Kevin “Paper” Brown (Carver), Migeal “Rusty” Williams (The Finishing Visionary), Ryan “Big Twin” McLean, Rayon “Small Twin” McLean, Melbourne “Six” Allen, Carley “Taniel” Nichols (Studio All-Rounders), with Norman Maxwell (Boilermaker) joining towards the end production for PORTENT. [13] Facey shared, “My team is very important […] They help me to produce [this work], and I in turn help them through the opportunity of mentorship [and employment].” After receiving training from Facey, studio team members have gone on to apply their skills to other opportunities, such as making dental prosthetics.[14]

Facey and her dedicated team of collaborators take trees that were witnesses to colonial atrocities and sculpt them into tributes celebrating Jamaica’s flora, fauna, and emergent creolized culture. This arrangement is largely a result of post-colonial relationships to land, and rewriting these relationships demands more durational government-led land reparation initiatives. In the meantime, as Facey and her team take gradual first steps away from histories of oppression and work towards relationships of mutual dependence, PORTENT demonstrates a community coming together with the lofty goal of crafting the sublime. It is also a milestone for Facey’s artistic development: formed by the fire of controversy, she has come to a deeper understanding of her place within the Jamaican context, and uses this positionality to build a more equitable creative practice.

The Crossing (2023) is an impressive structure in scale and meaning, and holds a candid response to Ode to Pig (2024)’s vision for a utopian Jamaica free from its past. A 10-foot long, four-headed crocodile stands boldly atop an overturned cast iron vat once used to boil cane juice into sugar to be exported to the colonial metropole. The piece’s title references the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and acknowledges Jamaica’s past as a commercial entrepôt and military garrison and present as a garrison-entrepôt, while offering a hopeful but not overly optimistic outlook.[15] [16] The overturned vat signals the end of formal colonial occupation, but its continued presence suggests the perpetuation of colonial legacies in the present. The Crossing (2023) echoes anthropologist and curator David Scott’s framing of the post-colonial experience as tragedy rather than romance: “In tragedy, the future does not appear as an uninterrupted movement forward, but instead as a slow and sometimes reversible series of ups and downs.”[17] As the Caribbean wrestles with its complex present and continued colonial legacies, PORTENT remains open to The Potential for Something Magical to Happen.

[1] Laura Facey and Melinda Brown, Exhibition Programme for PORTENT: The Potential for Something Magical to Happen, Exhibition Programme, October 13, 2024, 2.

[2] Edna Manley was married to Norman Manley, the founder of the Jamaican People’s National Party and the first Premier of Jamaica.

National Library of Jamaica, “The Rt. Hon. Norman Washington Manley (1893–1969),” n.d., https://nlj.gov.jm/project/rt-hon-norman-washington-manley-1893-1969/.

[3] Marcus Garvey’s Black nationalist rhetoric promoted social and political self-actualization, which aligned with the Harlem Renaissance “New Negro” debates and resonated with Jamaica’s creolized middle class in the 1930s and 1940s, of which Edna and her husband Norman (politician and the first Premier of Jamaica) were part.

O’Neil Lawrence and National Gallery of Jamaica, “The Art of Jamaican Sculpture – Curator’s Essay,” National Gallery West, January 21, 2019, https://nationalgallerywest.wordpress.com/2018/03/18/the-art-of-jamaican-sculpture/.

[4] Laura Facey (artist), online video interview with author.

[5] Laura Facey and Melinda Brown, Exhibition Programme for PORTENT: The Potential for Something Magical to Happen, 2.

[6] “Whereas in the United States, the category white generally means to exclude all those who have any ‘non-white blood,’ in Jamaica, ‘white’ has been an inclusive category that embraces not only Anglo-Saxons, but also Jews, Syrians, and even some people with multiracial or Chinese background[s].”

Holger Henke, The West Indian Americans. The New Americans. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED454321.

[7] Jamaica National Heritage Trust. “Mount Plenty Great House,” n.d. http://www.jnht.com/site_mount_plenty_great_house.php

[8] Matthew Bishop and Courtney Lindsay, ODI Global, “Breaking the Cycle of Debt in Small Island Developing States (SIDS): the Jamaican Experience,” May 2024, https://media.odi.org/documents/Jamaica_case_study.pdf.

[9] Amanda Sans Pantling and IMDb, “Paddlin Spirit (Short 2016) | Short, Documentary,” December 8, 2016, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt13439368/.

[10] Laura Facey (artist), online video interview with author.

[11] Veerle Poupeye, “A Monument in the Public Sphere: The Controversy About Laura Facey’s Redemption Song,” Jamaica Journal 28, no. 2–3 (2004): 39, https://www.laurafacey.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Jamaica-Journal%E2%80%94vol-28-2-3%E2%80%94LauraFacey.pdf.

[12] Laura Facey (artist), online video interview with author.

[13] Laura Facey, “About – Laura Facey,” n.d., https://www.laurafacey.com/about/.

[14] Laura Facey (artist), online video interview with author.

[15] Vincent Brown, “The Jamaica Garrison,” in Harvard University Press eBooks, 2019, 44, https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674242081-004.

[16] Here I apply Roitman’s term “garrison-entrepôt” to describe Jamaica’s present as a military-commercial nexus, such as being a transshipment point for illicit drugs.

Janet Roitman, “The Garrison-Entrepôt (L’entrepôt-garnison),” Cahiers d’Études Africaines 38 (1998): 297, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4392872.

[17] David Scott, Conscripts of Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), https://www.dukeupress.edu/conscripts-of-modernity.

PORTENT by Laura Facey is on view at the artist’s studio in Bellevue, St. Ann, Jamaica until February 2025.