In June 1989, shortly after the artist’s death from AIDS, Robert Mapplethorpe’s traveling retrospective The Perfect Moment was abruptly cancelled ahead of its opening at the now-shuttered Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. It was an era stiffened by the hidebound social mores championed by the likes of the Republican senator Jesse Helms, among many others. The political landscape crackled with the rancor of conservatism, and cultural institutions were not insulated from the din. The gallery defended its decision as a precautionary measure taken to avoid backlash from right-wing politicians who derided Mapplethorpe’s photographs as obscene, indecent, and immoral at a time when funding from the National Endowment for the Arts was heavily scrutinized. Responding promptly, the Washington Project for the Arts—an alternative contemporary art space—agreed to present the nearly thwarted exhibition. It opened some weeks later in July

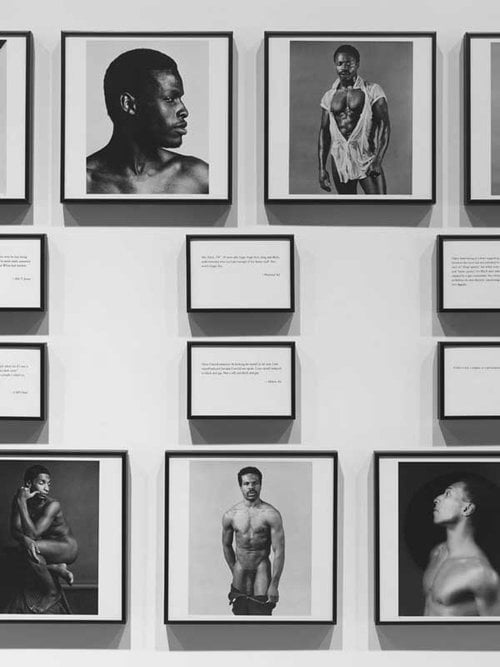

We are now thirty years removed from that presentation of The Perfect Moment, and WPA has mounted a sharp exhibition marking its anniversary. Deftly conceived by the artist Tiona Nekkia McClodden, a curator whose rigorous engagement with key antecedents of queer life and art continues to prove bracing and insightful, There Are No Shadows Here: The Perfect Moment at 30 is a part-symposium, part-exhibition project that examines the vexing artistic legacy of Robert Mapplethorpe. Though Mapplethorpe is the ostensible subject of this commemorative effort, he remains conspicuously absent from the gallery’s walls. Absent, too, is the hagiographic varnish often applied to projects of this sort, masking a more deeply felt portrait of the artist beneath its surface. This is not a retrospective endeavor, a backward glance on the life he led and the art that issued from it. Instead, the show considers Mapplethorpe’s unwieldy influence through an unlikely pairing of queer portrait photographers of different generations: the late George Dureau and D’Angelo Lovell Williams.

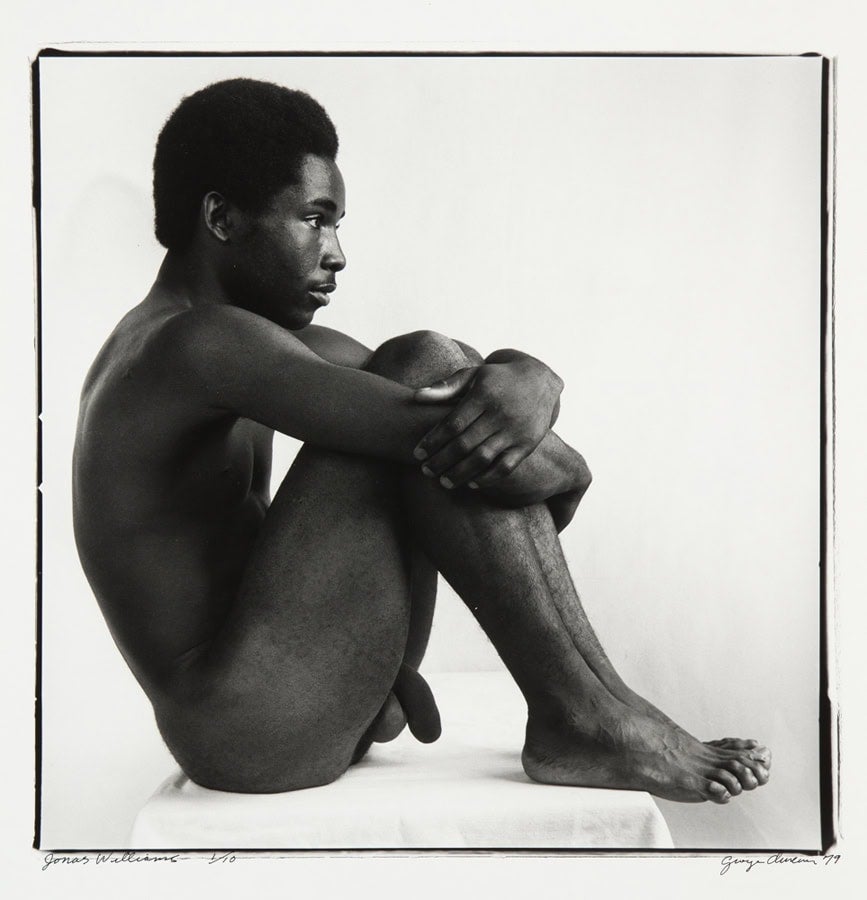

Dureau was born in New Orleans in 1930 and chronicled the demimonde of the city’s fabled French Quarter in the 1970s and 80s. His subjects were the dwarves, amputees, and especially the Black American men whom he met, and frequently cruised, in the neighborhood, and later photographed in the studio he maintained for more than two decades. Mention of Dureau invariably summons the presence of his better-known contemporary Robert Mapplethorpe, whom Dureau counted as a friend and occasional rival, although Dureau’s activity preceded Mapplethorpe’s own by some years. (The two photographed each other and corresponded during their careers.) Such is the extent to which Mapplethorpe hovers specter-like over the canon of queer photography. Whereas Mapplethorpe submitted his subjects to the rigors of his exacting, highly aestheticized tableaux, Dureau’s pictures demonstrate an openness between photographer and subject. In a Dureau picture, something of the sitter’s personality remains intact.

Williams was born in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1992. His vivid self-portraits are illuminated by an intense focus on his own interiority. His photographs in the exhibition are remarkable in part for the complexity of the self that they yield, one that Mapplethorpe and Dureau’s Black subjects were in some ways sealed off from in their sittings. How might Ajitto have rendered his image? Or Bob Love and Glen Thompson and Clarence Williams? What selves would they have offered? Would they have seen what Williams sees?

The exhibition features fourteen photographic prints: ten silver gelatin prints by Dureau interspersed with four color pigment prints by Williams. This display makes use of juxtapositions that emphasize uncanny, and often startling, congruences between their pictures. A self-portrait in which Williams clasps his elongated neck rhymes with a portrait by Dureau in which the subject delicately prods his chin with an outstretched finger. An enigmatic shot of Williams baring his legs, partly obscured by a billowing black garment, rests alongside a Dureau portrait of a man with a leg amputation, clad in gleaming, black leather pants, gripping an umbrella as both a prop and prosthetic. And so Dureau comes to converse with Williams, one queer sensibility seamlessly animating another. Arrayed throughout the show are handsome floral arrangements that adorn white pedestals, cleverly alluding to the numerous floral still lifes produced by Mapplethorpe throughout his career—wilting portraits of the artist in absentia.

The exhibition generously provides copious reference materials in the form of books and ephemera examining issues related to the show organized on a long table, revealing the rich depth of McClodden’s scrupulous research and archival-based curatorial method. One can find monographs by Dureau and Mapplethorpe, Kobena Mercer’s Welcome to the Jungle, Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, Stuart Hall’s Essential Essays, the yellowed pages of an issue of Outlines, and a lightly worn copy of Essex Hemphill’s Ceremonies. While there, I leafed through a copy of Mapplethorpe’s Black Book—initially published in 1986—peering, in page after page, at all those Black men, largely nude, some of whom were harshly lit, many of whose bodies were contorted into rigid forms and angular shapes, with taut shoulders and tense muscles, and all crossed by Mapplethorpe’s fantasy of the Black phallus.

The book, with its totemic title emanating a dark mystique, courted mixed reception. Some, like the writer Jarvis D. Moore, who penned a loving tribute to Mapplethorpe in a 1989 issue of BLK magazine, were swayed by the rarity of what it represented, believing that Mapplethorpe had ushered the Black male nude—so long obscured—into the lofty, glittering province of fine art. “The genre of Black male photography is richer because of him,” Moore declared. Others, notably the poet Essex Hemphill and the artist Glenn Ligon, were more critical. Glenn Ligon: America, lying not far off from Black Book, contains the series Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1993), in which Ligon anatomized, through dozens of annotations culled from various sources, the racial and erotic subtext of Mapplethorpe’s pictures. No matter the tenor of the critique, Black Book was framed and fancied itself as a reverent homage to Black masculinity: the late Ntozake Shange wrote poems for the foreword.

The inclusion of these contextual materials allows viewers to glean a nuanced understanding of the scope of Mapplethorpe’s output and influence, with all its charisma, contradictions and idiosyncrasies, and outright odiousness. “I’m still somewhat into Niggers [sic],” he wrote to Jack Fritscher, founder of Drummer magazine, in the late 1970s. “He used the term always with affection,” Fritscher dreadfully qualified.

Perhaps neither Mapplethorpe nor Dureau could have imagined an instance in which one of their various Black male sitters would vacate their respective studios, seize a camera, and turn the lens squarely on himself, vulnerable and self-possessed, or that the narrow canon of queer photographic practice would eventually give way to other visions of the Black male body—to those of, say, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Lyle Ashton Harris and Iké Udé. D’Angelo Lovell Williams imaginatively expands this lineage of queer Black men who have produced portraits in their own image.

Curated by Tiona Nekkia McClodden and featuring photographs by George Dureau and D’Angelo Lovell Williams, There Are No Shadows Here: The Perfect Moment at 30 was on view at the Washington Project for the Arts in Washington, D.C., from July 18 through August 17.