Sometime in the 1960s, Peggy Nolan was sitting at a shiny black table in a factory that made penicillin pills. Her job was to sort them by hand, the broken pills from the not broken ones. She’d pull a string and the pills would slide down a chute. The good ones went into a bucket underneath the table, and the broken ones got sucked down by vacuum. “It was the most tedious, soul-killing job I ever had,” she says. One day, an inspector arrived on site, and Nolan, who describes herself as jumpy and nervous, accidentally kicked over the bucket of good, life-saving pills without realizing. She heard the crunch of the foreman’s footsteps approaching her. “He made me stand up and saw that I was pregnant,” Nolan says. “So I got fired.”

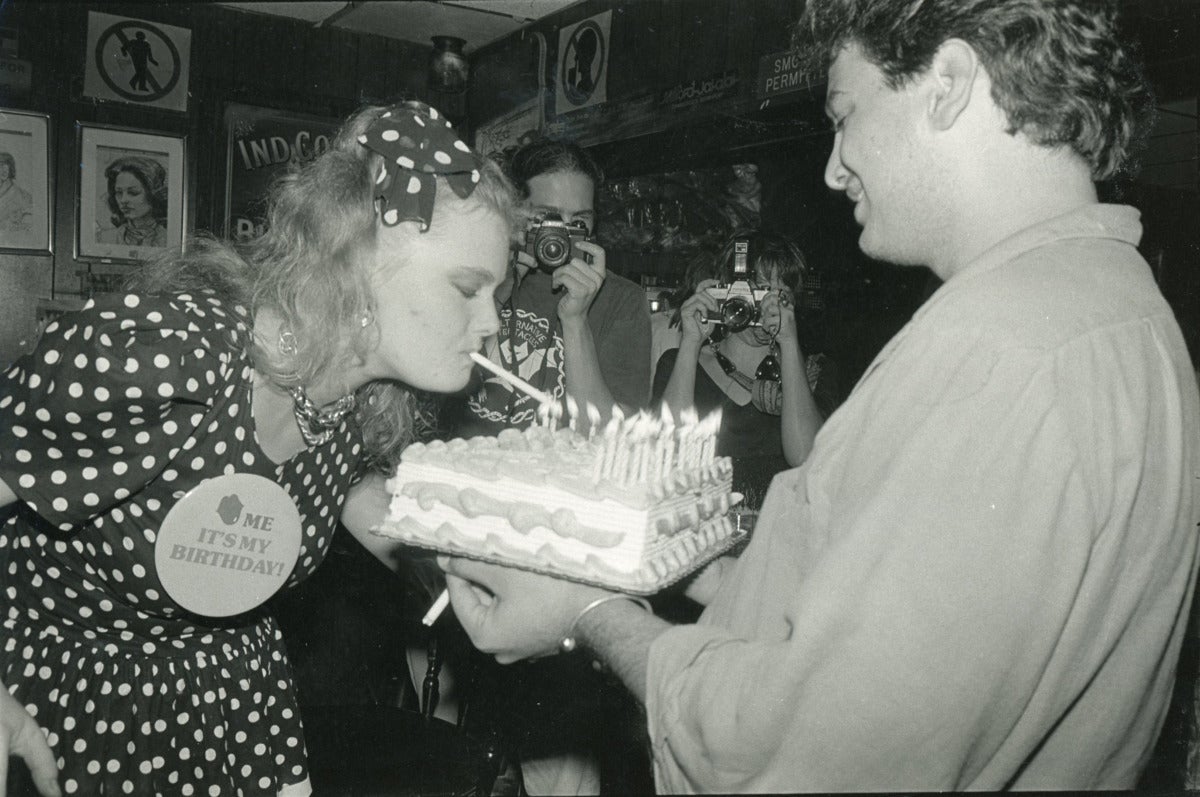

The subjects of Nolan’s photographs from the 1980s and 1990s are almost entirely her children and their proximates. In one of her black and white photographs from this period, a young woman grips a cigarette tightly between her lips as she leans over to light it with one of the candles on her birthday cake. A young man is smiling as he holds the cake, a cigarette between his fingers, a magnetic therapy bracelet on his wrist. According to the number of candles, the young woman is around 24 years old. She’s wearing a polka dot dress and a big pin that says “Kiss me it’s my birthday.” Two other people in the photo are taking photos with their own cameras—cameras, not phones. The four of them are at Sid’s Pub in Miami. There’s a payphone on the wall. There’s a sticker too, which reads “Milford Jai Alai,” and, it turns out, Milford, Connecticut had a short lived obsession with Jai Alai, the Basque sport which has enjoyed a history in South Florida, the place where Nolan has lived for many years. Lighting a cigarette with a birthday cake candle is exactly the kind of ironic excess a 24-year-old would perform.

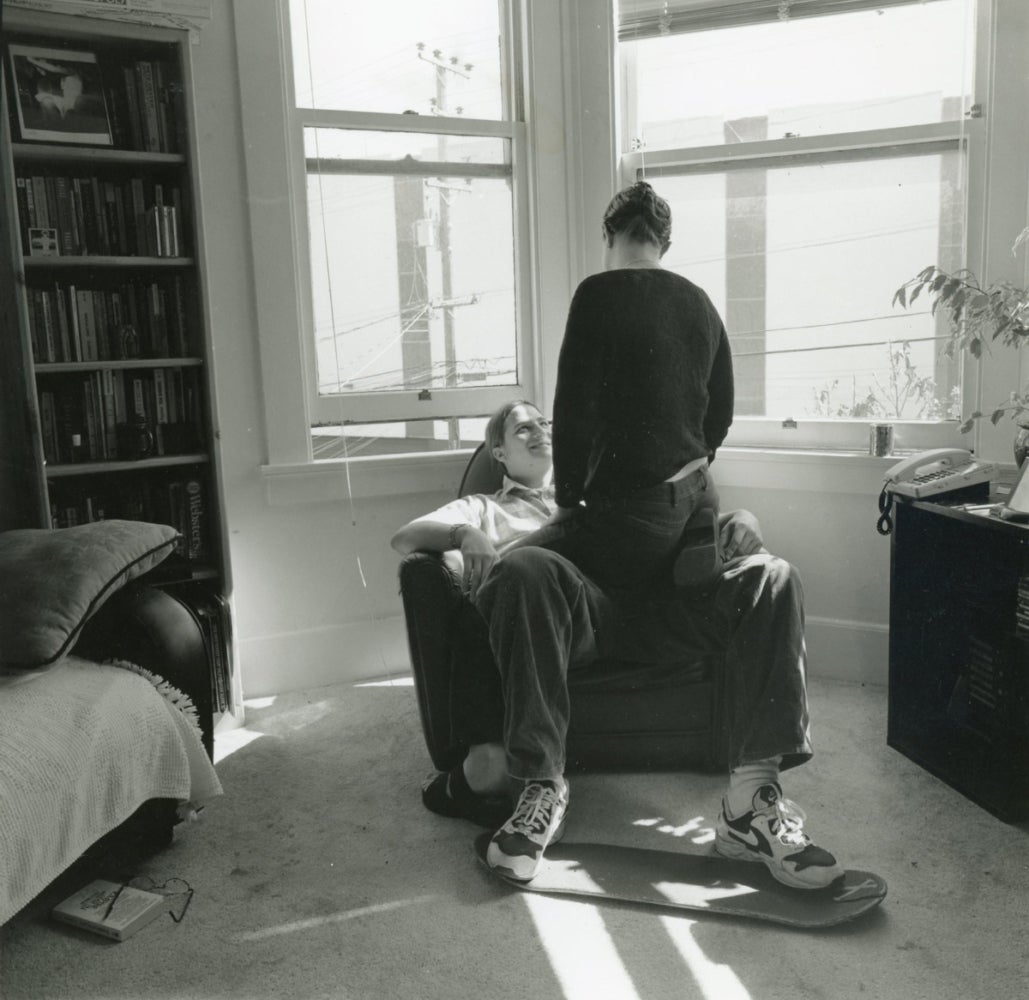

In another one of Nolan’s photographs, a young man is sitting on an armchair in a living room. A young woman is sitting on his lap. Her back is turned to the camera, but we can see the smile upon the young man’s face. The smile is sweet, anticipating, the kind that comes when a lover sits on your lap. He’s wearing Nikes and his feet are on top of a skateboard deck that has no trucks or wheels. You can feel the abrasive grip-tape on top, and the soft, slightly stained carpet underneath. Her right leg is bent back, resting on his thigh and against her butt. He seems to be pinching her foot teasingly. There’s a bookcase full of books and some CDs. Rectangular columns of light. A powerline and a massively tall wall beyond the windows. The shocking clarity of first love. In another one of Nolan’s photographs, three boys, who, I would guess, are 10, 13, and 16, are flexing their biceps, mocking masculinity at three critical phases of becoming whatever a man is. In another photo, a young woman is laying on her back on the couch, the phone to her ear. She’s twirling the plastic cord between her toes. In another photo, a young man is driving and passing a joint to the person in the backseat. The driver has the tensed look of someone on the verge of exhaling. All the scenery passing by is a blur.

She had seven kids, though she would have had more. “I wanted a lot of my friends in my gene pool,” Nolan says. She studied creative writing at Syracuse University. Lou Reed was in her cohort. Nolan dropped out, then moved to South Florida, where she and her husband lived in a trailer with no air conditioning on a mango farm. Nolan made lunch for the farmworkers. For fun the family went to the beach at night.

They eventually moved into a development called Rainbow Village in Naranja, just north of Homestead, a largely agricultural area. Nolan describes Rainbow Village as part of a “hippie” HUD program, where migrant workers were asked what they would want in their housing. The design included traffic circles, where the kids could play safely. To live in Rainbow Village, Nolan says, you had to have a family of five or more, and make no more than $250 a week. Of the thirtyish families that lived there, only two were white, and Nolan is happy that her kids grew up there because they learned not to be racist. In one of her photos, her son, who looks to be about nine, is wearing a tuxedo, surrounded by six Black friends. There’s a palm tree, a car parked in a front yard, and a street sign that reads SW 270 Street. Everyone is smiling huge for the camera except for Nolan’s son, whose smile is pursed. He’s playing it cool.

In the nineties she started bringing her kids to hang out with the members of Kreamy ’Lectric Santa, a punk band that played often at Churchill’s Pub, the dive venue in Little Haiti, Miami. “I brought my kids there, which was probably not good parenting, but, whatever. One Halloween they got on stage and threw their candy into the audience when Kreamy was playing.” In one of Nolan’s photos a group of young people are hanging out outside Churchill’s, and a young woman is blowing bubbles with a bubble gun. Her photos from this period are like wildlife photography, capturing teenagers. They’re caught in their natural state. “I know how to be sneaky,” Nolan says. “What you really want is to become slightly invisible.”

Nolan started taking photos at the age of 40, when her dad gave her an old Nikon and said ‘Make pictures of the grandchildren.’ During the eighties and nineties, she worked exclusively in black and white film, and most, if not all, of these photos are untitled. She never had photos of her own childhood, so she wanted to show her kids what it was like to grow up. What it was physically like. “We had no money,” Nolan says, “so if they wanted to have some money they had to get a job.” And yet, they still had adventures, an easy tenderness, the sun. Nolan captured the expressions they made, the friends they had, the feeling of necking on the living room couch with a sibling right next to you, who cares. The discovery, as a child, of pretzeling your body into a freaky crab-like position. Making faces. Mosh pits, cartwheels, going topless in rainstorms.

The young people in Nolan’s photos, her children and their friends, are in the midst of their lives. Rather than the prison of a split second, Nolan’s photos capture the easy freedom of youth. “They have body language that goes away when you become an adult,” she says. Every photograph of Nolan’s is intimacy enshrined. And yet, there is something impersonal about them. The people in her photographs are more like objects of study. The photos are not sentimental; yet they capture sentimentality. Only in the way an artist can, and only in the way an artist who is also their subjects’ mother can. When Nolan takes photos of her kids, “They cease to exist as family and they become something else.” What do they become, once the film has developed? It’s as if you’re looking at your own memories. Images of a life not your own, but easily confused for such.

Peggy Levison Nolan’s work is on view as part of the Orlando Museum of Art’s Florida Prize in Contemporary Art Show from June 3rd until August 27th, 2023.

This piece was published in partnership with Oolite Arts as part of a project to increase critical arts coverage in Miami-Dade County.