Messages are bits of communication, whether they’re verbal, textual, or symbolic, that relay information from one to another. They are invitations, emails, letters, and DMs–an amorous note, or a breakup text. Messages, as defined in the Oxford English Dictionary, are the salient points or distilled fragments of truth that reveal the central themes of political, social, or moral importance.

Three Raleigh exhibitions traverse the polarities between the transparency and opacity of messages rendered in cloth. Layered Legacies: Quilts from the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts at Old Salem and Community Threads at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh (NCMA) and Material Messages: The Tales That Textiles Tell at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design at NC State University examine quilting and textile traditions that have survived generations.

Quilts are symbols of pride and heritage, and while their fabrication has long been seen through the lens of leisure, quilts and textiles have also been used as tools of protest and resistance. There has long been a marked difference in how these objects are perceived. What all shows uncover through historical and contemporary works is a subtext of exploited, underrecognized labor that’s often shrouded by the beauty of craft.

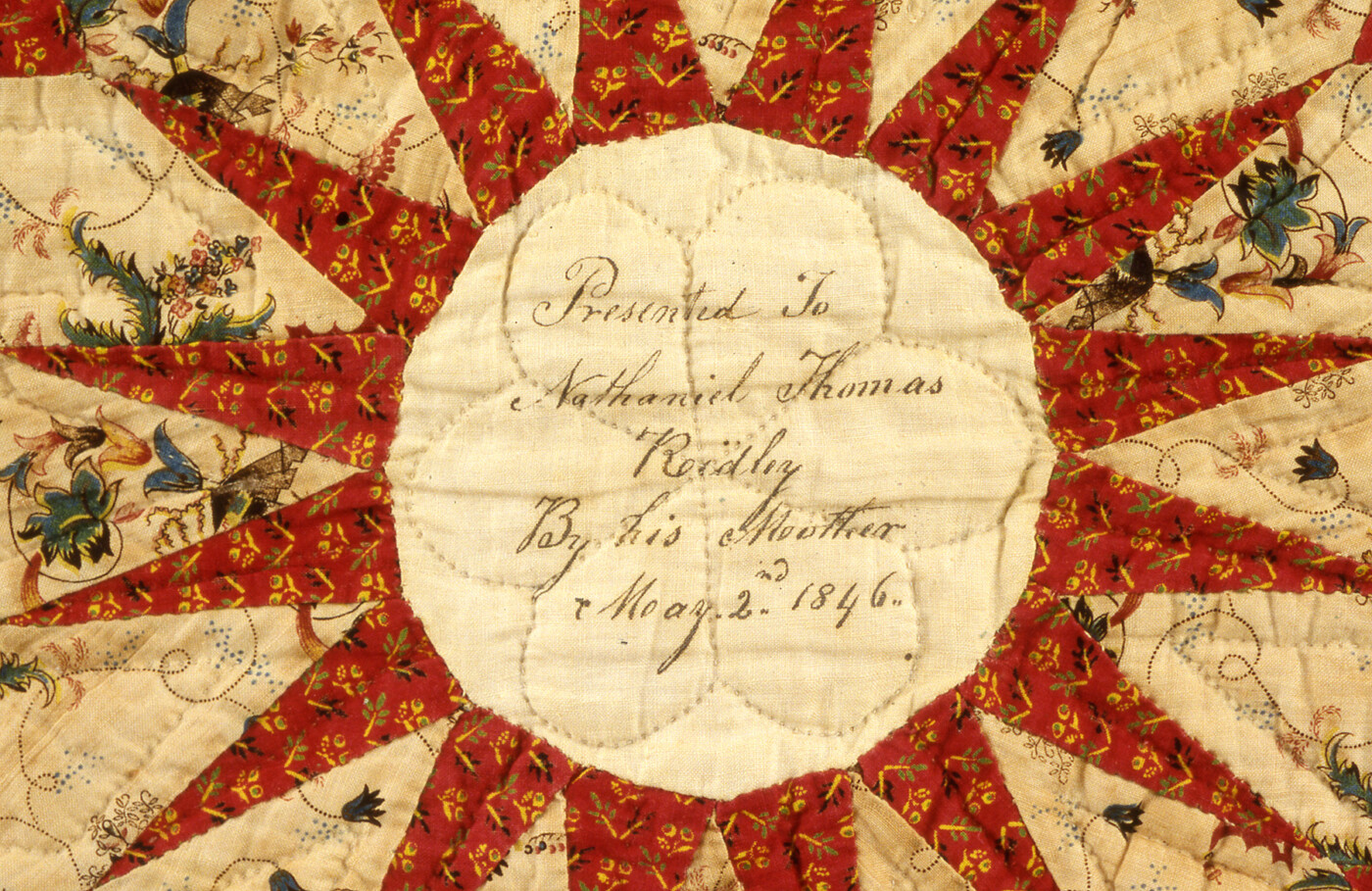

Layered Legacies: Quilts from the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts at Old Salem is a celebration of technique, highlighting the craft practitioners between the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries who used time-honored quilting traditions related to applique, knotting, patchwork, and whitework to create bed linens that were passed down through generations as treasured items of remembrance. These aren’t necessarily objects that immediately conjure the comforts of hearth and home; instead, what’s immediately apparent is the skill and mastery of form, shape, and scale.

The show at NCMA opens with seven whitework bed coverings made from white linen embroidered in white floche thread. They are placed against a blue background, a color that reflects light, making whites appear whiter; their presence conjures chaste notions of purity and virtue that, when overlaid across the institution of slavery, grounds the exhibition in a complex, racially charged milieu.

This presentation focuses on early 1800s quilting practices that combined lavish, imported fabrics to turn these items of utility into markers of wealth and privileged status. Arbiters of this niche within the craft included Mary Ann Brownrigg who combined painting and quilting to create an ornately designed palampore panel featuring a menagerie of flora and fauna surrounding a tree of life that’s topped with a peacock; the tableau is bordered by a chintz fabric. A curious footnote in the wall text throughout the show acknowledges the role that enslaved labor likely played in the creation of the quilt, linking the origins of textile production to exploited labor. Of course, making this connection clearer would require a deeper dive into the Industrial Revolution vis a vis the textile boom that occurred with the innovation of the cotton gin and the significant import of enslaved labor in the South between 1790-1860 that made the production of fabrics, like those used in quilting, more accessible.

The increased demand for textiles also amplified the barbarity of the violent institution of slavery, which runs counter to the perception that quiltmaking was a civilized pastime practiced by privileged women of leisure; the reality is that enslaved labor was evident within every stage of the supply chain from the cotton fields and cotton mills to the needlework itself.

Using another quilt circa 1840-1850, curators attempt to draw a direct line between its owner, Hercilla Ann Achsah Meadors, and an enslaved laborer named Margaret, who likely played a role in the fabrication of the quilt by tracking down a descendant of the enslaved family. The additional context of enslaved labor felt like a loose thread that begged for a bit more unraveling. While acknowledging the presence of “hidden hands,” the show asks more questions than it answers about properly naming and crediting them.

As fiber arts continues to gain its overdue recognition within the art establishment, the scholarship around acknowledging and correcting the historical record that has concealed exploited labor demands more attention.

A poignant epilogue in the show came in the form of a quote from writer Julia Ridley Smith in her book titled, The Sum of Trifles (2021), hinting at the complicated legacies that remain hidden within the seams: “What is a quilt, after all, but a patchwork document, written in scraps and stitches, and stuffed with matter that, although we cannot see it, gives the thing its weight?”

Acting almost as a balm to the issues Layered Legacies touches on, the accompanying pocket exhibition and makerspace Community Threads presents three contemporary fiber artists who reflect a multidimensional approach to the medium through the range of topics, materials, and techniques they deploy in their work.

New Zealand-born artist Michelle Wilkie brings bold color blocking to her contemporary quilts that evokes the geometric, architectural look of 1960s supergraphics while still hinting at traditional quilting patterns. Her featured piece titled Study No. 3 (2020) is loosely inspired by the colorful abstracted grid patterns of Stanley Whitney, and features scraps of fabric grouped together in a rainbow gradient. Using a minimalist line with a maximalist color palette, Wilkie’s dichotomous works are full of contradictory details that harmonize with one another.

Aliyah Bonnette creates and paints narrative quilts that draw on her personal experiences and deeply rooted familial connections combining new ideas while preserving the integrity and history of the artform. Her piece titled You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty (2023) features a painted-on subject with a sense of self-possession that defies the uncertainty that appears to be looming around her, symbolized by the masked figures shrouded behind foliage. Her crown, made from cowrie shells, adds texture that punctuates the regalness of the subject.

Textile artist Patrizia Ferreira combines found plastics, beads, embroidery floss, and yarn in work that marries traditions emanating from her familial ties to Montevideo, Uruguay. A piece titled The Deluge (2024) is a meditation on consumerism; Ferreira stitched a female form who appears to be overtaken by a current of detritus while remaining anchored to a tree limb that’s entwined with her arm. Long threads of embroidery floss that flow from the bottom of the piece suggests that something new can come from chaos.

As fiber arts continues to gain its overdue recognition within the art establishment, the scholarship around acknowledging and correcting the historical record that has concealed exploited labor demands more attention.

Material Messages: The Tales That Textiles Tell at the Gregg Museum situates textile-based artworks as archival documents that commemorate history, celebrate culture, and honor traditions passed down over generations. A globally inclusive show, Material Messages presents clothing and textile traditions drawn from the Gregg Museum’s expansive collection, supplemented by contemporary fiber arts works; together, they create a diverse, intergenerational dialog around labor, love, and creative expression. Curator Precious Lovell foregrounds the communicative properties of cloth, choosing samples like the Adinkra of the Akan whose symbols convey messages, directives, truisms, and aphorisms from the largest ethnic group in Ghana.

A pair of indigo-dyed Ndop and Ukara cloths (n.d.) hang on one wall, billowing softly in the wake of passersby within the gallery. Their movement beckons a slow look at their intricate design patterns. Much like the Adinkra, Ndop cloth from Cameroon and the Ukara in Nigeria are nobility robes and secret society textiles that contain symbols and codes within the design that communicate messages between members of villages or lodges. Their fabrication is both laborious and time-consuming–raw material is printed in a grid format with designs that are stitched with dried raffia; the cloth is then dyed in indigo and dried. When the piece is cured and dried the raffia is removed, leaving behind a contrasting pattern in white.

While the Ndop is often reserved for nobility, according to wall text in the show, the Ukara is reserved for secret communication among members of a fraternal order called the Ekpe in eastern Nigeria. Animals and celestial shapes are layered on the geometric patterns of the grid; their code can only be deciphered by Ekpe members. It is thought that the Ukara is also imbued with a spiritual energy that reinforces the textile as a reverent, sacred representation of the Ekpe.

Additional examples of resist techniques using indigo are displayed in the show, including an indigo batik robe made by a Miao artist from Southeast Asia that’s created with a ladao, a wax pen that applies melted beeswax to white fabric that is then dyed–the wax is removed using hot water that reveals the final pattern. Other indigo fabric pieces include a deep purple colored veil made from indigo known as a tagelmust, or litham which is worn by the Tuareg, a nomadic tribe of men who wear the headdresses as a rite of passage when they turn twenty-five years old; it is believed that the veil wards off evil spirits. Many of the garments in the exhibition incorporate evil eyes and a form of embroidery mirror work, called shisha, which is found in Indian garments. Their reflective properties hold apotropaic powers.

These talismanic traits found in both the raw materials and the craft traditions themselves serve a purpose beyond an activity of leisure. Some of the most potent examples of this work are the tapestries that were created as symbols of resistance.

During a curatorial walkthrough of the exhibit, Lovell noted: “All of the communities in this exhibition have experienced imperialism, colonialism, exploitation of natural resources, marginalization, apartheid, discrimination, displacement, and all types of violence, yet they continue to express their cultures and humanity through their textile-making traditions.”

One example that is found later in the exhibition is a 1987 Chilean Arpillera made by a Peruvian artist from burlap cloth that features small, colorful, three-dimensional figures, including people, animals, and other signs of daily life that are stitched into the burlap base. The small figures in the cloth made from wool thread resemble Guatemalan worry dolls; they hint to the history of the origins of this craft. Arpilleras were originally made by women whose husbands were imprisoned, kidnapped, or killed under the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte. Through the process of creating arpilleras, women would come together to share their burdens in community, creating quilt squares that depict their lives under the violent regime.

Their tapestries were collected and sold by the Catholic church to raise funds that were used to support the creators’ families. When the Chilean government banned these works, the movement continued underground, and the tapestries were sold and distributed overseas. This collective creativity model spread to other Latin American countries after the 1970s.

What all of these shows demonstrate is the capacity for cloth to operate on a visual register that far surpasses the aesthetics of beauty, fashion, or comfort. These objects are markers of identity that unite, representing traditions that transcend borders. As vehicles for expression–of protest and pride–these items demand that we acknowledge the hands and the history behind the creation of these works, continuing to peel back the layers and decipher the messages they convey and the stories they tell.

Layered Legacies: Quilts from the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts at Old Salem and Community Threads are on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh through July 21, 2024. Material Messages: The Tales That Textiles Tell is on view at The Gregg Museum of Art & Design at NC State University through January 25, 2025.