Noah Simblist: This essay is meant to be a retrospective analysis of a project that the San Juan based artist Pablo Guardiola presented fall 2023, a project which, in and of itself, was a kind of retrospective look at a slice of the artist’s practice. One of the challenges in art criticism is how to write about an artist’s work without regurgitating the artist’s statement or press release. One option is to offer novel language for description or a particular interpretation; another is to rely on taste (“I like it”) or judgment (“it’s bad!”). I wanted to see how an act of writing could be more dialogical, allowing a back and forth in order to open up possibilities of meaning rather than declaring their absolute definition. Thankfully, Burnaway has a new annotation column to be able to do just that.

I have worked with Guardiola in his capacity as a co-director of Beta Local but this is the first time that we have been in extended dialogue about his work as an artist. I started by looking over the images of the exhibition then interviewed him about the project. After writing a first draft of this text, I then turned over to him for responses. The exchange led to what you are reading now. The result is an experiment in transparency and discursivity in relation to a text about an artist’s work.

*For readers to note, Noah’s text is found in purple (English) and orange (Spanish), while Pablo’s text is found in black (in light mode) or white (in dark mode).

As a note within a note, I took the title from Anunciación, a column by the writer Leila Guerriero. She writes, “An annunciation, an uncontainable holiness. It is not a relief or a truce. It is a static moment. A block of time. As if the world were standing still and exuding geometry. It is not euphoria. It is a tug without exaltations, a Baptist immersion. A trance. A levitation in which I understand everything. It hasn’t happened to me for a long time. But that doesn’t matter to me. What matters to me is knowing how many more times it will happen to me before everything is over. Four, five? I feel like I’m saying goodbye to everything.”1

In general, my titles come from the readings I am doing as I develop a project. These last two years have been marked by readings of Guerriero’s work.

As for the formal idea of a block of time, I am interested in pointing out the multiple time dimensions that operate in our archipelago. In this sense, our size as an island favors us, we can enter and leave these time dimensions quite easily and fluidly. An explicit example is the transitions between the countryside, the coast, and the city.

I was looking for a place that had historical significance, and that was not directly identified as a contemporary art space. Casa Aboy fulfilled those characteristics perfectly. Then, the plan was to design the exhibition in a way that was sensitive and simple to the space. Inevitably, many stories began to emerge and come to the surface following my presence in the house. This often happens in many of these spaces, where their history remains purely oral and passed on by spoken word.

There are certain expectations of how tropical contexts behave and, above all, how they look. Within these conditions, I worked on the construction of the images from other coordinates. First, the approach is one of process. I visited these places for a long time, developing relationships with these spaces and with the people who inhabit them. Little by little, I was also gathering information about these places. This information is not presented explicitly, but with a detailed look, small details begin to appear from the trail. It is also important to point out that these landscapes also have an allegorical charge, specifically about the possibilities within our context. It is incredible how much you can learn by spending time in these places, finding signs and particularities in something that the cliché has tried to make exist from a homogeneous condition.

This is Guánica Bay, where American troops entered the island in 1898. From the sea, you can see the island all the way to the Central Mountain Range. The structure Noah refers to is the entrance card, one of the guides for boats to orient themselves when entering the bay. Out of context, it looks like a piece of geometric abstraction. Many of the nautical signs could be pieces of this type, even of a constructivist nature.

Hurricanes completely disrupt the landscape, accelerating geological and natural cycles in an extreme way. This situation offered very interesting conditions, although it was also sad to see details that were not explicit before.

In the case of Puerto Rico, the climatic conditions, but above all the socioeconomic ones, create the conditions of perceiving that we live in a constant present, in a non-future. In different ways, clues and components of our memory are removed. Part of this memory is about the behavior of nature. In this sense, I am interested in the development of this before the human trace. In Puerto Rico, there are no primary forests, all these spaces have been intervened in multiple ways and scales by humans. However, our secondary forest is quite healthy and robust (for the moment). I am interested in working with this trace, and highlighting the ambiguity of time in these contexts. In relatively short periods, the forest can swallow any development or human intervention.

As I mentioned at the beginning, I wanted to be sensitive to the house and simple with my approach. I wasn’t interested in turning it into a white cube. I wanted to interact with it as if it were another landscape, which, mind you, is never neutral. So I worked around its attributes. I partially covered some of its windows, which made them stand out. I installed photographs on these screens, turning them into additional windows. My intention was for them to feel like portals. I installed works on both floors of the house. The first floor, the first threshold, was calmer. Here the the provenance of the contexts was more oblique, caught in intertwined branches and leaves. Here there were works where the origin of the contexts was more confusing. Different photographed places converge in the installation. In fact, the installation takes on other strategies, where there are photographs presented at different heights, and there are objects distributed throughout the space. Likewise, some furniture from the house was left where there were reference readings under stones and sticks.

It is worth noting that it is not only a tax haven for crypto-investors, but for all kinds of millionaires established in the US as witnessed through Act 60. The amount of land and housing properties that are being bought is absurd. In a super accelerated manner, entire neighborhoods are being transformed by the dynamics of short-term rentals, resulting in an increase in housing prices for local people. The touristification is super violent, and we are being forced to participate in speculation dynamics of what this implies that were not so present or on our minds several years ago.

A fundamental aspect of the project is to seek other ways of inhabiting our landscape, freeing it from colonial and neoliberal tropes. From other coordinates, this project proposes views to understand the framework that makes up this complex Antillean landscape. For this you have to try to be present and accept all its times. This landscape includes many contents within others, as well as all its temporalities – the geological time that produced the rock of the island, the time of growth and regrowth of the layers of jungle on top of these strata, and the cycles of colonialism that built on top of this, each leaving specific traces. The landscape is its present and it is also its trace, learning to read it beyond the surface opens new possibilities of imagining its future.

[1] Guerriero, Leila, Teoría de la gravedad.( Libros del Asteroide, 2020)

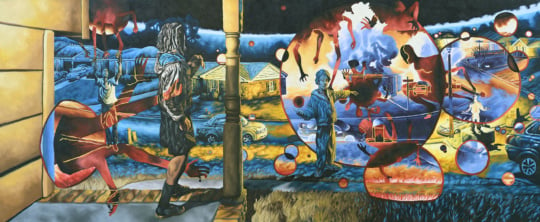

Pablo Guardiola’s Bloque de Tiempo (A block of time) is a body of work presented in an exhibition that takes as its subject both the topography of the Island of Puerto Rico and photography as a mechanism of representation. This title provoked a series of questions for me: How could an island be a block of time? How is an architectural structure a block of time? How is a photograph a block of time? If each could be thought of as a block, a unit of time, then how do these units accumulate in relation to one another?

These are the questions that animated Pablo Guardiola’s exhibition, Bloque de Tiempo in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 2023. The setting for the exhibition was Casa Aboy, the first photography gallery on the island, which has served as a space to think about documentary photography in Puerto Rico. Built in the early twentieth century in a tropical modernist style, it began as an important center for the political Left, the independence movement, and the queer community. For example, in the 1980s, it hosted activists engaged with the AIDS crisis. More recently, it has been used as a cultural center and exhibition space, still with a focus on the Puerto Rican Left.

Guardiola chose this as the site to present his project, supported by Maniobra (a granting program co-organized by Centro de Economia Creativa and the Mellon Foundation) and Sociedad del Tiempo Libre (a worker owned, artist run, cooperative production organization), to highlight a set of photographs that document years of walks through the island. From 2013-2023, the artist walked through the landscape, recording hikes with his camera in performing as an archaeologist, unearthing various histories along the way that were embedded in the landscape. The exhibition covered the past four years and a publication (going to press in the fall) expands to ten years of this peripatetic work. The block of time is also a unit of an artist’s life and practice.

In one image, a pyramid of green entangled vines rises from a watery horizon. In another, the silhouette of a banana leaf hangs over a mountainside at dusk. Violet clouds frame what could be either a moon or a lens flare. In a few images we see ancient, knotted vines. In another, a brick structure with arched apertures.

What is a tropical landscape? From a scientific standpoint, it might suggest a particular ecology that lives in a certain climate. But the notion of “tropicalia” might also suggest a particular cultural framing of space. For better or worse, there is an ideology projected onto it. The tropical landscape, from a colonial point of view, has historically been seen as pure and original, as if it was the garden of Eden. But this projection of untouched purity, interpreted through a Judeo-Christian lens, has also excited the extractive impulse of colonial reach.

In one photograph, Guardiola has depicted a bay that has a history of both Spanish and American colonialism. A site of entry for these forces, it now has a scaffolding, about twenty-five feet tall, on which hangs a long, vertical orange flag with a white stripe down the center. That photo of the pyramid of green growth was an abandoned rum refinery, an industry fraught with colonial histories. But these images aren’t dramatic, or overly saturated with formal gestures to highlight these narratives, instead, they are presented matter of factly, devoid of a contemporary human presence.

Puerto Rico has also endured the onslaught of natural violence in these last ten years. Perhaps most significantly through the ravages of hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. A couple of photographs included in the show depict dense bramble grown over mounds of rock and fallen tree limbs. It’s possible that these images are records of the aftermath of these storms, but they could also index slower cycles of decomposition. The island is a block of time made up of layers of desiccated organic matter, some produced through sudden explosions of radical change and others more banal. While this geological time makes up the overwhelming majority of the islands sedimentation, there also are layers of cultural intervention: the rum factory built to distill sugar cane into alcohol along with the tobacco warehouses built to dry and roll cigars for export.

In the installation, the works were presented as if they were windows, like holes punched through the walls to reveal the landscape surrounding the gallery. In one instance, a new wall was installed in front of a bay of windows to mount a photograph, replacing one aperture with another. Interspersed throughout the installation are objects collected along Guardiola’s walks: a tree branch, a rock, a pair of rum bottles. These objects act like photographs in the sense that they are indexes of their origin. But unlike the objects, the photographs have their own sense of time built into them, a capture of light in the tiny fraction of a second, a shutter’s click. This is the kind of time that Roland Barthes famously described as a cut in time, a cut between the present and the past. A cut that immortalizes a moment that otherwise would be buried in history’s rubble.

In a text about this project Guardiola writes:

The tropical forest can be overwhelming, but with time you learn to read it. At the moment, this forest is threatened, not so much by agriculture or because people move to live there. Now it faces speculation onslaught and its development by foreign agents, with their foreign capital.

A new threat is identified, a twenty-first century version of colonization through gentrification. The Puerto Rican landscape that these photographs depict becomes a territory vulnerable to financialization – where material realities become commodified and commodities become defined by their debt to equity ratios, a process in which capital accumulation is necessarily dematerialized. This goes way beyond the traditional models of colonial extraction of resources like sugar or coffee. In recent years, the island has been a tax haven for cryptocurrency and consequently, has brought new outsiders on top of the hordes of tourists that pour off of cruise lines that dock in the harbor. Paradoxically, the island landscape has become both a symbol of original purity and a futurist projection of technocapitalism.

In the wake of the hurricanes, both local and federal governments failed to adequately care for a wounded community. Basic civic infrastructure like electricity or clean water have remained in disrepair. What is often blamed is an insurmountable debt. In an all too typical symptom of neoliberalism, flows of private capital are the main strategy enacted to prepare for the next storm. As Guardiola says, the forest can be overwhelming, and if one were to take it as a metaphor for the tangle of forces that govern it, with time it too can be read. With Bloque de Tiempo, the artist has provided a lesson in how to read the forest and the ways in which time is embedded in its knotted core.

A manera de nota dentro de la nota, el título lo saqué de Anunciación, una columna de la escritora Leila Guerriero. Ella escribe: “Una anunciación, una santidad incontenible. No es un alivio ni una tregua. Es un momento estático. Un bloque de tiempo. Como si el mundo se quedara quieto y exudara geometría. No es euforia. Es un tironeo sin exaltaciones, una inmersión bautista. Un trance. Una levitación en la que entiendo todo. Hace mucho que no me sucede. Pero eso no me importa. Lo que me importa es saber cuántas veces más me sucederá antes de que todo se acabe. ¿Cuatro, cinco? Siento como si le estuviera diciendo adiós a todo.”1

Por lo general, mis títulos provienen de las lecturas que estoy haciendo a medida que voy desarrollando un proyecto. Estos últimos dos años han estado marcados por las lecturas del trabajo de Guerriero.

En cuanto a la idea formal de un bloque de tiempo, me interesa señalar las dimensiones des tiempo múltiples que operan en nuestro archipiélago. En este sentido, nuestra escala nos favorece, podemos entrar y salir de estos de manera bastante fácil y fluida. Un ejemplo explícito son las transiciones entre el campo, la costa, y la ciudad.

Estaba buscando un lugar que tuviera una carga histórica, y que no fuera identificado directamente con un espacio de arte contemporáneo. Casa Aboy cumplía con esas características perfectamente. Ya luego, el plan fue diseñar la exhibición siendo sensible al espacio. Inevitablemente, muchas historias comenzaron a surgir a partir de mi presencia en la casa. Esto suele suceder en muchos de estos espacios, donde su historia continúa siendo puramente oral.

Hay ciertas expectativas de cómo se comporta y sobre todo cómo se ven los contextos tropicales. Dentro de esas condiciones, trabajé la construcción de las imágenes desde otras coordenadas. Primero, el acercamiento es uno de proceso. Visité estos lugares por mucho tiempo, desarrollando relaciones con estos espacios y con las personas que los habitan. Poco a poco, también iba recopilando información de estos lugares. Esta información no se presenta de manera explícita, pero dentro de una mirada detallada comienzan a manifestarse pequeños detalles desde el rastro. También es importante señalar que estos paisajes también tienen una carga alegórica, en específico sobre las posibilidades dentro de nuestro contexto. Es increíble todo lo que se puede aprender pasando tiempo en estos lugares, encontrando señales y particularidades en algo que el cliché se ha esforzado en que exista desde una condición homogénea.

Esta es la bahía de Guánica, por donde las tropas estadounidenses entraron en 1898. Desde el mar, se puede apreciar la isla hasta la Cordillera Central. La estructura a la que Noah se refiere es la tarjeta de entrada, una de las guías para que las embarcaciones se orienten al entrar a la bahía. Fuera de contexto, parece una pieza de abstracción geométrica. Muchas de las señales náuticas podrían ser piezas de este tipo, inclusive de corte constructivista.

Los huracanes intervienen de manera total con el paisaje, acelerando ciclos geológicos y naturales de manera extrema. Esta situación ofreció condiciones bien interesantes, aunque también tristes de ver detalles que antes no eran explícitos.

En el caso de Puerto Rico, las condiciones climáticas, pero sobre todo las socioeconómicas, crean la condiciones de percibir que vivimos en un presente constante, de un no futuro. De distintas maneras, se nos remueven pistas y componentes de nuestra memoria. Parte de esta memoria es sobre el comportamiento de la naturaleza. En este sentido me interesa el desenvolvimiento de esta ante el rastro humano. En Puerto Rico no hay bosques primarios, todos estos espacios han sido intervenidos de múltiples formas y escalas por humanos. Sin embargo, nuestro bosque secundario es uno bastante saludable y robusto (por el momento). Me interesa trabajar con este rastro, y resaltar la ambigüedad del tiempo en estos contextos. En periodos relativamente cortos, el bosque se puede tragar cualquier desarrollo o intervención humana.

Como mencioné al comienzo, quería ser sensible con la casa. No me interesaba convertirla en un cubo blanco. Me planteé interactuar con ella como si fuera otro paisaje, los cuales en este proyecto, nunca son neutrales. Así que fui trabajando alrededor de sus atributos. Cubrí parcialmente algunos de sus ventanales, lo cual los resaltaba. Instalé fotografías en estos biombos, convirtiéndo estas en otras ventanas. Mi intención era que se sintieran como portales. Instalé trabajos en ambos pisos de la casa. El primer piso era más sosegado, para mi era el primer umbral, ya luego el segundo se volvía un poco más caótico, en donde varios tropos convergían. Aquí había trabajos donde la procedencia de los contextos resultaba más confusa. Distintos lugares fotografiados convergen en la instalación. De hecho la instalación adquiere otras estrategias, donde hay fotografías presentadas a distintas alturas, y hay objetos distribuidos por el espacio. Así mismo se dejaron algunos muebles de la casa donde había lecturas de referencia debajo de piedra y palos.

Es necesario señalar, que no solo es un paraíso fiscal para crypto-inversionistas, sino para todo tipo de millonarios establecidos en los EEUU por medio del Act 60. La cantidad de tierra y de propiedades de vivienda que están siendo compradas es absurda. De manera super acelerada, barrios completos están siendo transformados por las dinámicas de los alquileres a corto plazo, teniendo como consecuencia un alza en los precios de vivienda para las personas locales. La turistificación es super violenta, y se nos está obligando a participar de dinámicas de especulación que no eran tan presentes hace varios años atrás.

Un aspecto fundamental del proyecto es buscar otras maneras de habitar nuestro paisaje, liberándolo de los tropos coloniales y neoliberales. Desde otras coordenadas, este proyecto propone miradas para entender el entramado que compone este complejo paisaje antillano. Para esto hay que procurar estar presente y aceptar todos sus tiempos. Este paisaje incluye muchos contenidos dentro de otros, así como todas sus temporalidades. El paisaje es presente y es rastro, aprender a leerlo más allá de la superficie abre nuevas posibilidades de imaginar su futuro.

[1] Guerriero, Leila, Teoría de la gravedad.( Libros del Asteroide, 2020)

Bloque de Tiempo de Pablo Guardiola es un conjunto de trabajos presentados en una exposición que tiene como tema tanto la topografía de la Isla de Puerto Rico como la fotografía como mecanismo de representación. Este título me provocó una serie de preguntas: ¿Cómo puede una isla ser un bloque de tiempo? ¿Cómo puede una estructura arquitectónica ser un bloque de tiempo? ¿Cómo puede una fotografía ser un bloque de tiempo? Si cada uno puede ser pensado como un bloque, una unidad de tiempo, entonces ¿cómo se acumulan estas unidades en relación unas con otras?

Estas son las preguntas que animaron la exposición Bloque de Tiempo de Pablo Guardiola en San Juan, Puerto Rico en 2023. El escenario de la exposición fue Casa Aboy, la primera galería de fotografía de la isla, que ha servido como espacio para pensar la fotografía documental en Puerto Rico. Construida a principios del siglo XX en un estilo modernista tropical, comenzó como un centro importante para la izquierda política, el movimiento independentista y la comunidad queer. Por ejemplo, en la década de 1980, albergó a activistas comprometidos con la crisis del SIDA. Más recientemente, se ha utilizado como centro cultural y espacio de exhibición, siempre con un enfoque en la izquierda puertorriqueña.

Guardiola eligió este lugar para presentar su proyecto, apoyado por Maniobra (un programa de subvenciones coorganizado por el Centro de Economía Creativa y la Fundación Mellon) y Sociedad del Tiempo Libre (una organización de producción cooperativa dirigida por artistas y propiedad de los trabajadores), para destacar un conjunto de fotografías que documentan años de caminatas por la isla. De 2013 a 2023, el artista caminó por el paisaje, registrando caminatas con su cámara mientras actuaba como un arqueólogo, desenterrando varias historias a lo largo del camino que estaban incrustadas en el paisaje. La exposición cubrió los últimos cuatro años y una publicación (que se imprimirá en otoño) amplía a diez años de este trabajo itinerante. El bloque de tiempo también es una unidad de la vida y la práctica de un artista.

En una imagen, una pirámide de enredaderas verdes enredadas se eleva desde un horizonte acuoso. En otra, la silueta de una hoja de plátano cuelga sobre la ladera de una montaña al anochecer. Nubes violetas enmarcan lo que podría ser una luna o un destello de lente. En algunas imágenes vemos vides antiguas y nudosas. En otra, una estructura de ladrillos con aberturas arqueadas.

¿Qué es un paisaje tropical? Desde un punto de vista científico, podría sugerir una ecología particular que vive en un clima determinado. Pero la noción de “tropicalia” también podría sugerir un marco cultural particular del espacio. Para bien o para mal, hay una ideología proyectada sobre él. El paisaje tropical, desde un punto de vista colonial, ha sido visto históricamente como puro y original, como si fuera el jardín del Edén. Pero esta proyección de pureza intacta, interpretada a través de una lente judeocristiana, también ha excitado el impulso extractivo del alcance colonial.

En una fotografía, Guardiola ha retratado una bahía que tiene una historia de colonialismo español y estadounidense. Un sitio de entrada para estas fuerzas, ahora tiene un andamio, de unos siete metros de alto, del que cuelga una bandera naranja vertical larga con una franja blanca en el centro. Esa foto de la pirámide de crecimiento verde era una refinería de ron abandonada, una industria cargada de historias coloniales. Pero estas imágenes no son dramáticas ni están excesivamente saturadas de gestos formales para resaltar estas narrativas, en cambio, se presentan con naturalidad, desprovistas de una presencia humana contemporánea.

Puerto Rico también ha sufrido el embate de la violencia natural en estos últimos diez años. Quizás de manera más significativa, los estragos de los huracanes Irma y María en 2017. Un par de fotografías incluidas en la muestra muestran una densa zarza que crece sobre montículos de rocas y ramas de árboles caídos. Es posible que estas imágenes sean registros de las secuelas de estas tormentas, pero también podrían indicar ciclos más lentos de descomposición. La isla es un bloque de tiempo formado por capas de materia orgánica desecada, algunas producidas a través de explosiones repentinas de cambio radical y otras más banales. Si bien este tiempo geológico constituye la abrumadora mayoría de la sedimentación de las islas, también hay capas de intervención cultural: la fábrica de ron construida para destilar caña de azúcar y convertirla en alcohol junto con los almacenes de tabaco construidos para secar y enrollar puros para la exportación.

En la instalación, las obras se presentaron como si fueran ventanas, como agujeros perforados en las paredes para revelar el paisaje que rodea la galería. En un caso, se instaló una nueva pared frente a un ventanal para montar una fotografía, reemplazando una abertura por otra. Intercalados a lo largo de la instalación hay objetos recogidos a lo largo de los paseos de Guardiola: una rama de árbol, una roca, un par de botellas de ron. Estos objetos actúan como fotografías en el sentido de que son índices de su origen. Pero a diferencia de los objetos, las fotografías tienen su propio sentido del tiempo incorporado, una captura de luz en la diminuta fracción de segundo, un clic del obturador. Este es el tipo de tiempo que Roland Barthes describió célebremente como un corte en el tiempo, un corte entre el presente y el pasado. Un corte que inmortaliza un momento que de otro modo quedaría enterrado en los escombros de la historia.

En un texto sobre este proyecto, Guardiola escribe:

El bosque tropical puede resultar abrumador, pero con el tiempo se aprende a leerlo. En este momento, este bosque está amenazado, no tanto por la agricultura o porque la gente se mude a vivir allí, sino que ahora enfrenta la embestida de la especulación y su desarrollo por parte de agentes extranjeros, con su capital extranjero.

Se identifica una nueva amenaza, una versión del siglo XXI de la colonización a través de la gentrificación. El paisaje puertorriqueño que estas fotografías muestran se convierte en un territorio vulnerable a la financiarización, donde las realidades materiales se mercantilizan y las mercancías se definen por sus ratios de deuda a capital, un proceso en el que la acumulación de capital se desmaterializa necesariamente. Esto va mucho más allá de los modelos tradicionales de extracción colonial de recursos como el azúcar o el café. En los últimos años, la isla ha sido un paraíso fiscal para las criptomonedas y, en consecuencia, ha atraído a nuevos forasteros que se suman a las hordas de turistas que salen de las líneas de cruceros que atracan en el puerto. Paradójicamente, el paisaje de la isla se ha convertido tanto en un símbolo de pureza original como en una proyección futurista del tecnocapitalismo.

Tras los huracanes, tanto los gobiernos locales como los federales no han podido atender adecuadamente a una comunidad herida. La infraestructura cívica básica, como la electricidad o el agua potable, sigue en mal estado. A menudo se culpa a una deuda insalvable. En un síntoma demasiado típico del neoliberalismo, los flujos de capital privado son la principal estrategia puesta en marcha para prepararse para la próxima tormenta. Como dice Guardiola, el bosque puede ser abrumador y, si lo tomamos como metáfora de la maraña de fuerzas que lo gobiernan, con el tiempo también se puede leer. Con Bloque de Tiempo, el artista ha dado una lección sobre cómo leer el bosque y las formas en que el tiempo está incrustado en su núcleo anudado.