When not just a few lives are dignified to be publicly grievable, when the obituary covers the nameless and the faceless, when, like Antigone, we are capable of burying the Other […] then public mourning, making us more vulnerable, will make us more human.[1]

ADVERTISEMENTCristina Rivera Garza

It is hard to portray suffering and death. Be it a humanitarian crisis, a hate crime or a war, photography treads a thin line when trying to convey complex and painful stories. Whether an image falls prey to empty sentimentalism or gets caught in sensationalist tabloids, neither path gets us closer to understanding the context of violence. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag warns about these and other risks: “In a world in which photography is brilliantly at the service of consumerist manipulations, no effect of a photograph of a doleful scene can be taken for granted.”[2] A photograph can objectify its subject, turning an event or a person into something that may be possessed or pitied, and keeps us, onlookers, at a conveniently safe, strategic distance. As a result, we can hardly understand our own entanglement in those events. How, then, does one go about portraying death tolls and misfortunes too vast to be grasped?

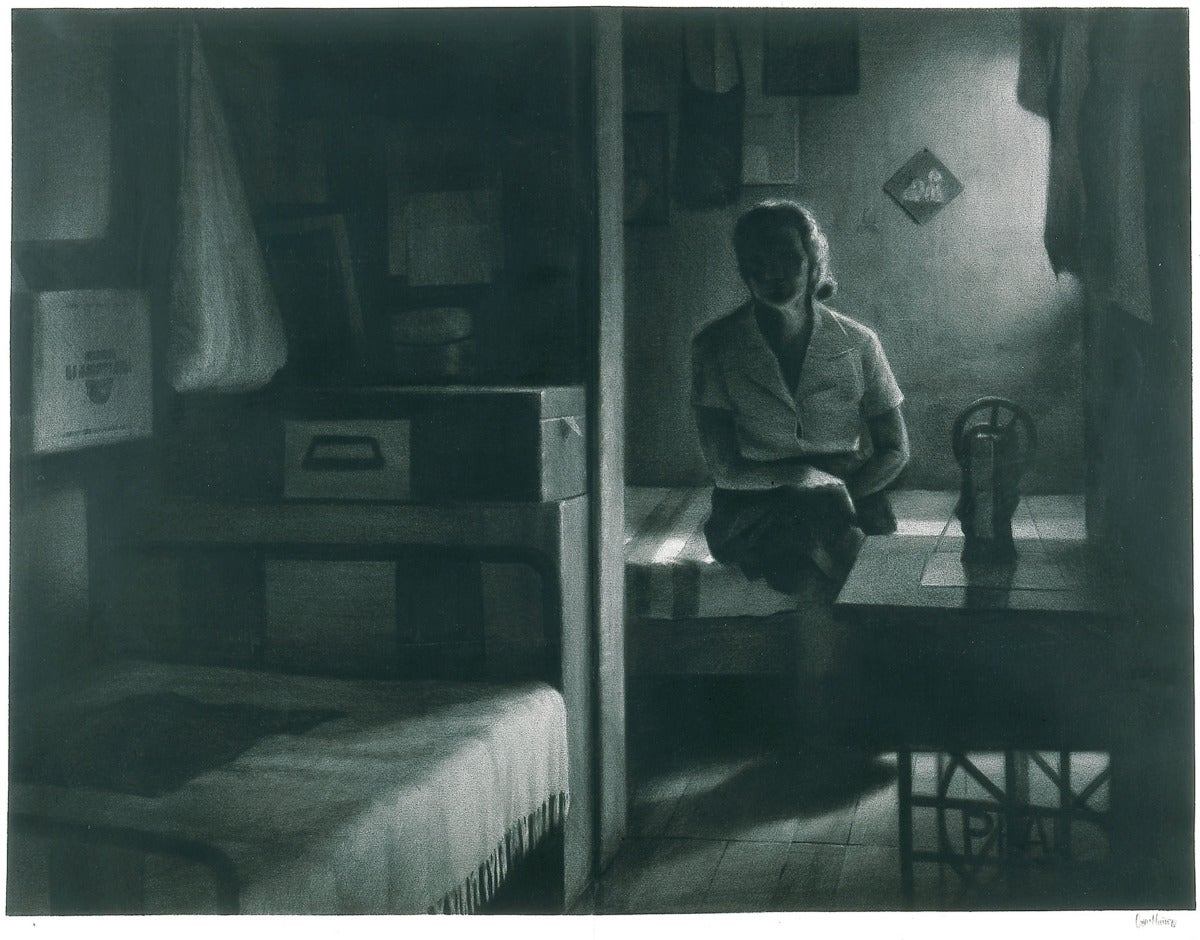

Artist Oscar Muñoz has explored this issue in several of his works, having experienced first-hand the anaesthetizing overexposure to images of violence produced during the seven-decade armed conflict that struck his native Colombia.[3] Oscar Muñoz: Invisibilia, on view at the Blanton Museum and previously at the Phoenix Art Museum, is the first mid-career survey of his artistic practice in the US. Known for his conceptual approach to photography, printmaking and drawing, Muñoz began his career in the late 1970s working with the unassuming medium of black chalk on paper –– where most saw only a rite of passage or a sketching tool, he found a path to a visual language of his own, depicting indoor domestic spaces with an uncanny level of detail. For instance, his series Interiores [Interiors] (1976-1981) turns the viewers into voyeurs, letting us spy on figures unaware of our presence. While the exhibition only features a couple of these early hyper-realistic works, they suffice in giving us a glimpse into how he sought to challenge the limits of the image, capturing the textures and atmospheres of sparsely-lit rooms, engaging us into what feel like actual memories.

The realization that no one’s gaze is truly innocent –not even the spectators’– and neither are the materials used in any artwork, began propelling Muñoz’s production in the 1980s. The perspective in his drawings shifts, and he turned to novel media to explore the material implications of capturing an image in other kinds of support. One of his most iconic works, Cortinas de baño (Shower Curtains) (1985-86), a series of plastic curtains that hang from the ceiling, epitomizesthis new direction: it is an immersive installation that displays the sombre contours of bodies that appear to be showering in the middle of the gallery. Naked and wet, these phantasmagorical figures seem disarmingly vulnerable, and their ashen skin also evokes cadavers at a morgue. To parse through the mortuary scene provided by these silkscreened shadows was an eerie experience, one that did not often inspire the audience to pose for selfies.

Muñoz widens such intimate dialogue between photography and death in two of his most well-known series. In Pixeles [Pixels] (1999-2000), he portrays the pixelated faces of anonymous people murdered in the crossfire between military forces and armed guerrilla groups in Colombia using coffee-stained sugar cubes. At the core of the country’s economy, these raw exports point to an earlier origin of violence and the sharp social and economic inequalities that have shaped the region. On the other hand, Proyecto para un memorial [Project for a memorial] (2005) is a five-channel video installation that documents the artist’s brush strokes tracing portraits sketched out with water over hot pavement. Based on actual photographs published in newspaper obituaries that Muñoz collected over the years, each face signals an individual who, nevertheless, remains anonymous, their story untold. Still, we are asked to look at each one intently, watch them appear and then sustain their portrait in our imagination as they begin to blur and fade. The artist attempts to create a space for quiet, public mourning through simple gestures that speak of the frustration and pain of an insurmountable loss, of having a loved one be murdered or “disappeared.”[4] No memorial can ever redress that wound, so he commits to the Sisyphean task of trying and failing, over and over again, to symbolically “bury the Other,” in the words of Mexican writer Cristina Rivera Garza. That is, his work enacts the drive to bring forth a time in which “not just a few lives are dignified to be publicly grievable, when the obituary covers the nameless and the faceless.”

Close to a fourth of the works in the exhibition can be classified as self-portraits, but far from a self-indulgent fixation they each tackle the subject in distinct ways and to very different effects. For example, in El juego de las probabilidades [The Game of Probabilities] (2007) the artist cuts into thin strips a series of old official photographs, passport-sized, threading different strands together to reassemble twelve images that look nothing like him. With this playful gesture, he undermines official documents as instruments of biopower, meant to help the state identify and surveil individuals through personal records. Conversely, the two-minute video Línea del destino [Line of Destiny] (2006) presents a more existential line of inquiry, introducing an analogy for the fleetingness of human life. We see his left hand trying to hold a small amount of water, and on its surface is Muñoz’s reflection, staring back at himself, and by extension, at us. Predictably, the water begins to escape the basin of his palm, and with it his portrait dwindles until only his empty hand remains. The video is looped and the ending foretold, yet you might find yourself rooting for a different finale, one in which Muñoz’s grasp managed to stop his self-portrait from slipping away.

The more recent works on display ponder the forms in which the digital revolution has recast our relation to photography. With the advent of cellphone cameras and social media, can anyone remember the last time they kissed a photograph goodnight? Or the last time they called on the framed image of a loved one to keep them company, to make them feel safe? This generational shift is invoked in works such as Doméstico [Domestic] (2013-16), a white marble shelf filled with white marble frames, all impeccably carved but still empty. Devoid of images, this sculpture doubles as a memorial to the brevity of human life, its fragility contrasting with the permanence of stones. Yet it could also be read as a monument to the very act of displaying and remembering through images, a nod to a period when the materiality of photography mattered and pictures were printed, framed and treasured in a different way.

The neighbouring installation, A través del cristal [Through the Glass] (2008-18), complements the artist’s nostalgic musings. In it, a tacky collection of digital frames placed along the wall displays portraits of individuals and couples, young and old. The subjects look back at us as if taken straight from people’s homes. However, a closer inspection reveals that every frame is playing a video of each photograph, filmed in its original setting – the digital screen bridges the domestic space (along with the ambient sounds of street vendors, radio broadcasts and chirping birds) and the museum gallery. Far from being transparent accounts of reality, photographs translate and transform the world around us. By making us look “through the glass,” the artist reminds us of the talismanic powers of photography, capable of constructing and reshaping identities – even in their current digital formats. Through Muñoz’s works we are invited to wonder about the lives they lead and to think of them as witnesses, as imperfect as our own memories are, as companions that affirm our existence.

[1] Cristina Rivera Garza. Grieving. Dispatches from a Grieving Country, translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker (New York: The Feminist Press, 2020), Epub. The author would like to acknowledge the influence of Rivera Garza’s thinking about pain and mourning in general as the basis for the reflections in this text.

[2] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 58

[3] For an overview of Colombia’s recent history and more information on Oscar Muñoz’s biography visit the timeline created by Florencia Bazzano on the Blanton Museum’s website.

[4] According to Colombia’s Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, between 1958, when the armed conflict began, and 2022 (a peace agreement was signed in 2016 after decades of raging civil war), it is estimated that 268,000 people were killed, out of which approximately two thirds were not combatants. The exact number remains unknown because many victims simply “disappeared”, their whereabouts unknown. This count does not include an earlier decade-long wave of political violence from 1948 to 1958, known as “La Violencia” (“The Violence”), when an estimated 200,000 died.

Oscar Muñoz: Invisibilia is on view at the Blanton Museum of Art thru June 5.