During my tenure as a university president, I could expect to be confronted daily by conflicting interests. If the major complaint was by students in a tizzy over parking and cafeteria food, you knew all’s right with the world. I empathize with Kennesaw State University President Daniel Papp, who has opened Pandora’s box labeled “censorship” and now faces, I assume, a maelstrom of criticism. Gone are those halcyon days of protest over just food and faculty/student parking.

To censor comes from the Latin censure, which means to render an opinion or to assess. I doubt the censorship of Ruth Stanford’s A Walk in the Valley was made on the basis of an assessment of artistic merit. In this case, the censorship of her work is suppression of information or ideas and a denial of free speech.

There are historical precedents from which we might learn. The installation of Thomas Hart Benton’s mural panel Parks, the Circus, the Klan, and the Press in a large room frequented by students on the Indiana University campus in Bloomington evoked outrage. Minority students, among others, have said the work makes them uncomfortable. After years, its appropriateness is still debated. The mural does call attention to a very unsavory period of Indiana history, when the Klan was a major political force. That piece of history should not be swept under the carpet of political correctness.

Michelangelo’s original Last Judgment depicted nude sacred figures. Under the pressure of the Counter-Reformation and much internal complaining, Pope Pius IV ordered coverings to be applied to sensitive areas. Unfortunately, this earned the artist charged with the task, Daniele de Voltera, the nickname “Il Braghetonne” or the “breeches maker.”

Manet’s Olympia caused a terrible stir when exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1865. So violent was the reaction, there was fear the work would be destroyed. The painting today, owing in no small part to its notoriety in the 19th century, is now seen as one of the great examples of midcentury painting in Paris. Marcel Duchamp submitted his Nude Descending a Staircase to the Société des Artistes Indépendants to appear in its exhibition in 1912. This time, the hanging committee, comprising fellow artists, asked him to voluntarily withdraw the painting or make adjustments. What would art history be today without these important, provocative, and now iconic works of art?

Closer yet in time, and perhaps reflecting a similar cause for elimination, is Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System as of May 1, 1971, in which Haacke pointed the finger at the extensive real estate dealings of the Shapolsky family. His exhibition of photographs and sheets of data about their properties documented and exposed their poorly maintained housing projects in the poorer parts of New York City. The work was to be shown at the Guggenheim Museum in 1971, but the director called Haacke and asked that this work not appear in the show. The artist refused to exclude it. The curator of the show was fired. What pressures were placed upon the museum and its staff?

Art is best judged on its aesthetic merits. A Walk in the Valley was produced by a well-known and experienced artist and, I am positive, was thoughtfully conceived and well executed. Her approach is a legitimate strategy in contemporary art. It is inappropriate to allow the censor to prejudge the response of the individual observer or the opportunity to see the work and engage the many issues that surround it.

Universities have, for centuries, served as the locus for allowing the free exchange of ideas and expression. The power of art is affirmed and serves an important social role because of its ability to provoke thought, debate, and even protest. Fortunate for the artist, nothing could have done more to enhance the importance of her work. Inclusion of Stanford’s work would have provided a learning opportunity—an activity that needs to be safeguarded in our universities.

The author would like to thank Dr. William Ganis, Chair of the Department of Art at Indiana State University, for calling attention to the Haacke work.

Lloyd W. Benjamin III

President Emeritus

Indiana State University

Opinion: A Former University President on the History of Art Censorship

Related Stories

Features

Announcements

Call For Artists

Zines | Making (Book)Ends Meet: Making Artist Books in Florida

In a special week-long editorial series on zines in anticipation of Burnaway's Book//Zine fair, Florida-based artist Paul Shortt speaks to the art of tabling a zine fair.

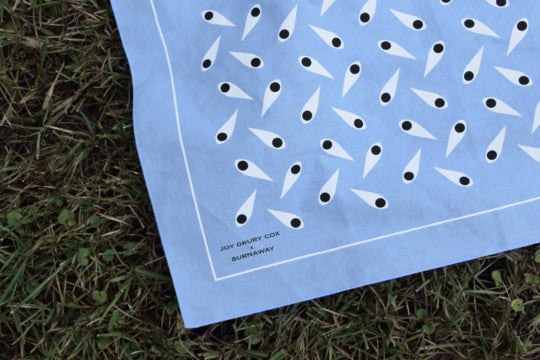

‘Watching, Looking, Seeing’ by Joy Drury Cox – A Burnaway Artist Edition

Burnaway is excited to continue our Artist Editions with a bandana by Joy Drury Cox inspired by neighborhood crime watch signs.

Call for Artists: October 2025

Our monthly round up of opportunities includes the PhotoWork Junior Fellowship, a semester-long residency program in Little Rock, and an artist residency in the Dominican Republic.