Bottle caps and jar lids: little pieces of plastic and metal that are indubitably useful but simultaneously forgettable. Conceptual artist Gabriel Orozco’s 1994 installation Yogurt Caps, in which he placed four clear Dannon yogurt lids on four walls of the Marian Goodman Gallery, is evidence of their inconspicuousness. You could’ve walked into the gallery and not noticed anything at all. Sculptors like El Anatsui, on the contrary, make the unspectacular spectacular. What appears to be a colossal, glimmering tapestry from afar reveals itself as worthless trash, thousands of bottle caps, metal bits, solid waste sewn and stitched together. Critic and professor Stephen Best calls this an inverse trompe l’oeil. “Where trompe l’oeil wants you to mistake it for an object in the world, and not to see it as art, an Anatsui, inversely, wants you to mistake it for art and not see it as an object in the world.”[1] In addition to waste’s readiness for aesthetic manipulation, it tells us something: about value, about global networks of production, circulation and consumption, about what’s left over.

What’s left over– Topo Chico and Coca-Cola bottle caps– hung at the bottom of threads fixed to a floating sculpture of white wooden dowels shaped into a dowsing rod, an ancient, trachea-like divinatory tool used to locate groundwater. This delicate behemoth was suspended in front of a large canvas that seemed to be, at first glance, the result of multiple layers of painting and stripping. A second look discloses order: perfect, light blue circles of different sizes, enmeshed with one another and with the abstract splotches of pastel. The bottle caps from the sculpture, dowSING and sCRYing (2019), produced shadows that haunted the canvas, Indigeneity as Commodity (2019), and beyond, creeping onto the empty gallery walls. In each bottle cap was a small mirror, which you might have not noticed unless you got close enough – at the risk of seeing a fragment of yourself.

These were the first two pieces I saw by the multi-disciplinary artist Ana Hernandez. I was an employee at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art when it hosted an exhibition on the New Orleans-based Level Artist Collective in 2019, co-founded by Hernandez alongside Horton Humble, Rontherin Ratliff, John Isiah Walton and Carl Joe Williams.

Raised in California, Hernandez moved to New Orleans about fifteen years ago for work. Prior to relocation, her reference point for histories of colonialism, capitalism and extraction in the states was the West. Seeing the influence of colonial Spain and France on the built environment of New Orleans was an entryway into new research projects. Much of her artistic practice became invested in space- and place-making in the American South, but given the city’s proximity to Central America, Hernandez has pursued throughlines that run across continents as well.

The unobtrusive Topo Chico and Coca-Cola bottlecaps of dowSING and sCRYing, for example, are one such throughline. These caps are the physical traces of a century-plus long relationship between two multinational corporations that have jointly profited off resource extraction, exploitative labor practices and the appropriation and commodification of indigenous cosmologies and iconography. Coca-Cola’s acquisition of Topo Chico in 2017 is only the tip of the iceberg.

St. John the Baptist Church in San Juan Chamula is also known as the Coca-Cola Church, because the church’s attendees, largely Tzotzil Mayans, have replaced sugar-cane liquor pox with Coca-Cola for their cleansing ceremonies. It’s inside and around this 16th-century church that Hernandez found the Coke bottle caps. The Topo Chico caps were hers, the remains of her own consumption. Hernandez told me she notices bottle caps most after it rains, because they’re filled with water. In this way, their function changes. They become receptacles of something, rather than mere appendages, mere trash. Like water itself, dowSING and sCRYing transforms discarded bottle caps into vessels– metal condensations of historical social relations.

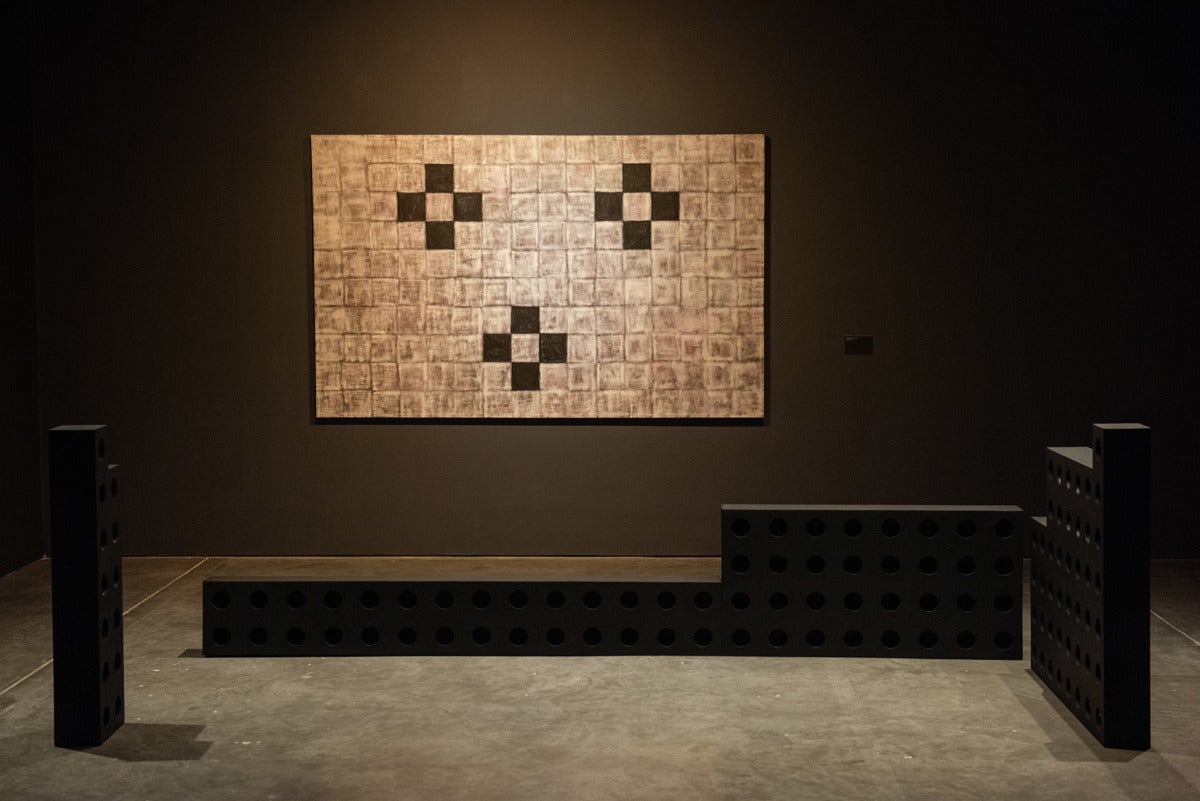

Indigeneity as Commodity doesn’t look like it once did. Hernandez painted over the canvas. It lives on today as We prayed for rain (2020), a quiet work of art with muted neutral colors and a gridded visual structure. The grid is a complicated thing, not least because of its historicization. The dominant historiography of the grid is narrow and exclusionary. To discuss the grid at a museum or an art history seminar, for example, often means the same thing: Rosalind Krauss and October, Pete Mondrian and European modernism. The design of We prayed for the rain, however, was inspired by a textile that her aunt gifted her, Hernandez explained. She chose the title because her parents participated in rain-making ceremonies.

“When people talk and think about extraction, it’s usually about natural resources,” Hernandez said. “That was one of my main focuses for a while, but I wanted to expand toward knowledge and knowledge systems.” As Maori educator Linda Tuhiwai Smith has famously theorized, “knowledge and culture were as much part of imperialism as raw materials and military strength. Knowledge was also there to be discovered, extracted, appropriated and distributed.”[2] With We prayed for the rain, Hernandez highlights the tension between the ubiquitous appropriation of indigenous craft and its simultaneous relegation to the primitive and non-modern.

Centering the wisdom and scientific-thinking of indigenous peoples is at the forefront of Hernandez’ mound photography, part of a larger, ongoing series called By Way of Air, Land, and Water, which Hernandez exhibited alongside We prayed for the rain at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans’ 2021 SOLOS show. The series foregrounds Black, Indigenous and people of color’s histories of survivance and resistance in Louisiana and beyond. Between 2018 and 2020, Hernandez visited and photographed mounds in Louisiana, Mississippi, Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin. From Poverty Point to Aztalan, the photographs are in black-and-white, which allows us to see them as a family, Hernandez noted, fundamentally interconnected.

The mounds cannot be contained by the photographic frame– they exceed beyond our purview, unable to be objectified or fully discerned. I feel small looking at them. They fill the whole space and desire beyond it. When I asked Hernandez about her photographic intentionality, she responded, “it wasn’t about photographing the mounds, it was about visiting and paying respect to these sites.” If we dispose of questions of authorship, we ought at the same time abandon our deeply ingrained attachment to photographic indexicality. Hernandez’ mound photographs assume neither a fully autonomous author nor a passive, evidentiary reality. Instead, following critical theorist Kaja Silverman, the mounds unfold themselves to us analogically through the photograph.[3]

In a time when the precarity of Louisiana and its inhabitants feels magnified – due to climate change and its uneven consequences on coastal landscapes, the criminalization of abortion, and an ongoing pandemic, to name a few factors – Ana Hernandez’ artistic practice is sobering. She slowly weaves together long and irreducibly interconnected microhistories of dispossession that illuminate critical political and economic conjunctions in our social reality, while also centering invisibilized art, architectures and epistemologies of marginalized peoples in the South and beyond. “The focus of my work is to educate myself first and foremost and if I’m able to help enlighten and empower others, that’s great as well,” said Hernandez, “It’s about envisioning… not being complacent or complicit, and hopefully contributing.”

[1] Stephen Best, None Like Us: Blackness, Belonging and Aesthetic Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018) 45

[2] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Dunedin: Otago University Press), 61

[3] Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy or the History of Photography, Part 1 (Stanford: Stanford University Press); In this book, Silverman reevaluates the history of photography, settling neither for accounts of the photograph’s constructed nature nor its status as a mere index of reality. Instead she considers key theorists of photography who together form a lineage of thought that posits the photograph as an analogy for its referent. For Silverman, the world analogizes and thus reveals itself to us through the photograph.