In Houston, a muted Gatorade yellow-green sky signals the arrival of a complex weather event. It is immersive, uncanny, hypnotic, and followed by naturally calculated chaos, moment-to-moment stability, and the arrhythmic pounding of seemingly unaffiliated realities colliding. One can find protection from such “energetic disturbances” in the lower level of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH), home to the solo exhibition Olivia Erlanger: If Today Were Tomorrow curated by Patricia Restrepo and designed by Jeremy Schipper.

T minus 4

Olivia Erlanger: If Today Were Tomorrow provides an opportunity to think of infrastructures as multiple objects in orbit. In an interview with the architect and writer Keller Easterling, Erlanger inquired, “Personally, I wonder how infrastructure decisions affect the construction of identity and the performance of self. Or if it’s the inverse, if constructing one’s disposition is a reflection of these invisible forces.”1 Erlanger is inspired by the “myth of home ownership following World War II” and a broader “semiotics of suburbia.”2 Such semiotics can be traced to Space Race era rhetorical narratives—the imperative to embrace limitless growth and that space-scientific discovery would enhance the quality of life. This government project could not be more evident in the years when NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center (JSC), came to Houston. Brief glimpses of JSC history punctuate this essay—advantageous plot points and crafty contexts—that tether Erlanger’s exhibition to the layered worldbuilding of Houston and its identity as Space City.

At CAMH, the exhibition design echoes the floor plans of mid-century home interiors, the spatial strategies of natural history museums, and aspects of orbital spacecraft. As a result, visitors tend to move on a somewhat elliptical path through the adjoining compartments or zones of the subterranean exhibition. Within and between these compartments are cultural associations that shift depending on each visitor’s entry and exit. One space built of multiple free-standing walls has an exploratory atmosphere oscillating between a science museum and an antiquated laboratory. The wall structure of another compartment, where planet-like sculptures are mounted, gives the illusion that it was extracted from some radial architecture. At the same time, its framing components resemble grand picture windows. There is a paired-down living room setting with exposed two-by-fours and a video projection that serves as a metaphor for the drab living quarters of a spacecraft prototype. In an area where CAMH’s brutalist architecture is most exposed is a simple exhibition resource center; opposite this is an installation of polished aluminum arrows. The space evokes a chart room and an airport lobby.

T minus 3

Established southeast of Houston in 1961, MSC symbolized progress, tangentially promoting “spaceflight as a biological imperative and a means of extending U.S. free enterprise, with its private property claims, resource exploitation, and commercial development, into the solar system and beyond.”3 Houston embraced its new Space Age identity and played a starring role in the renewed American frontier mythology.

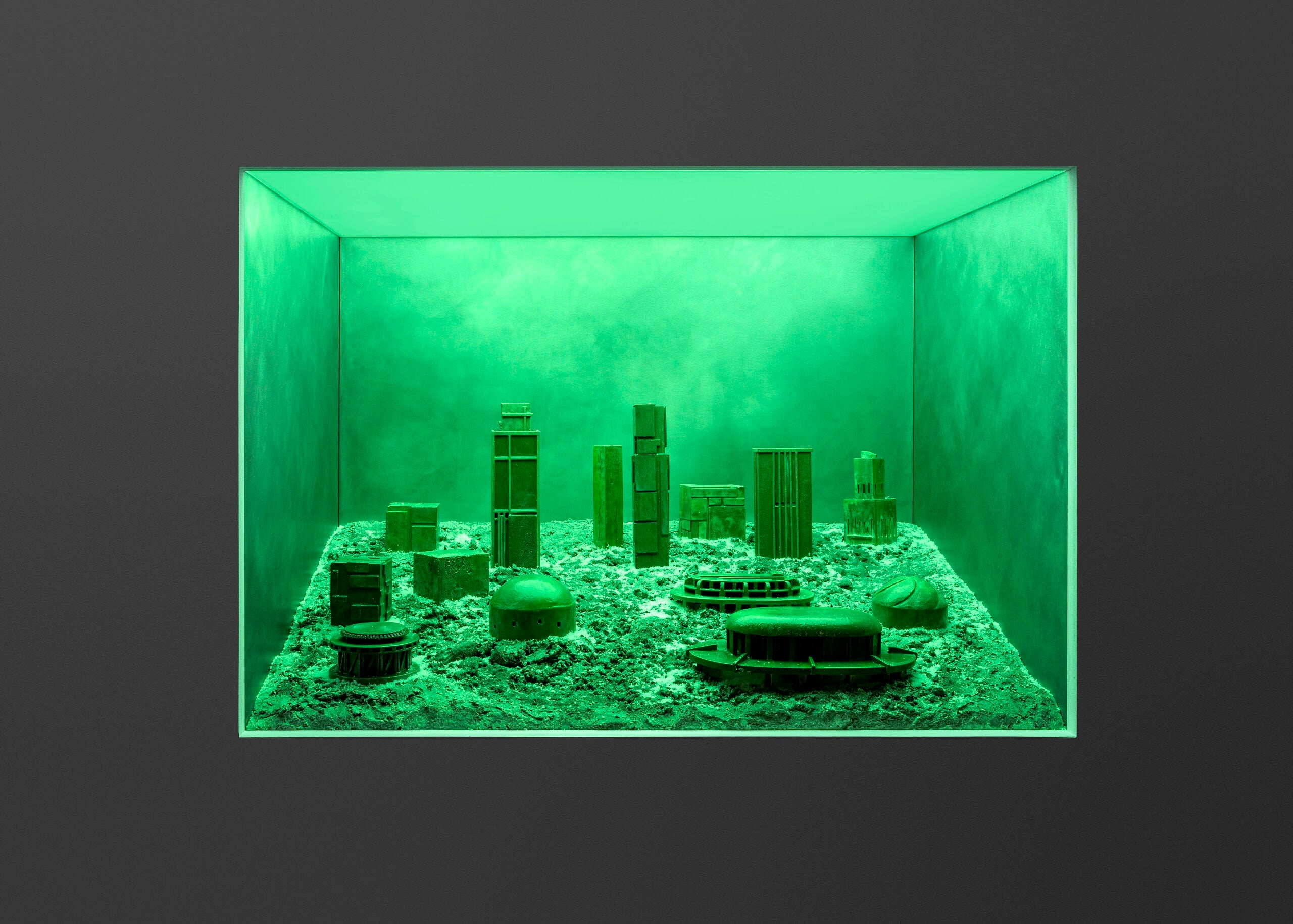

Four deeply color-saturated dioramas in the exhibition invite detailed examinations of their glowing interiors. The alluring (extra)terrestrial landscapes of Yellow Sky (2024) and Orange Sky (2024) tap society’s willingness to support something as wildly speculative as planetary tourism. Green Sky (2024), with a nod to Houston’s Astrodomain architecture, reminds one of the promise and problem of extra-planetary colonization. Blue Sky (2024) stings of prestige-seeking government administrations that extoll turn and burn achievements. These works may not be directly related to the arc of the Apollo lunar landing missions. However, when grafted onto this history, these displays model how public imagination contributed to the institutionalization of the Space Race during the Cold War.

T minus 2

Within a year of MSC’s instantiation, Houston experienced rapid, multi-sector economic growth, skyrocketing land value, and vast suburban development. Humble Oil built a sprawling complex with “an enormous residential area whose ultra-modern homes would epitomize the impact of the Space Age on American architecture.”4 Developments invested in infrastructures, including telephone companies, private power plants, medical facilities, and shopping centers. MSC, the epicenter, was considered in and of itself a mini-city.

Antimeridian (2024) and Prime meridian (2024) are planet-shaped sculptures with dramatically sized depictions of suburbia and infrastructure embedded in their terrestrial surfaces. Their extraordinary proportions act as relational illustrations—for instance, the suburban enclave surrounding MSC was produced in relation to unprecedented government-funded space-oriented technology R&D. Prime meridian is displayed as if one is viewing it from outer space. Instead of seeing some beautiful celestial planet, we see an unnatural but playfully hued one covered with homogenous suburban sprawl.

T minus 1

Skylab, NASA’s first space station, launched three crewed missions. At JSC, astronauts were required to evaluate Skylab’s habitability, including its environment and architecture, crew mobility, food management, hygiene, and housekeeping. These evaluations were “not in terms of the crews’ physiological and psychological reactions to those provisions, but in terms that may be useful to the designers of future spacecraft.” This instilled a mentality in which crew members became part of the machinery of the spacecraft, or the machinery of the spacecraft became part of the crew.5

“Olivia Erlanger: If Today Were Tomorrow” provides an opportunity to think of infrastructures as multiple objects in orbit.

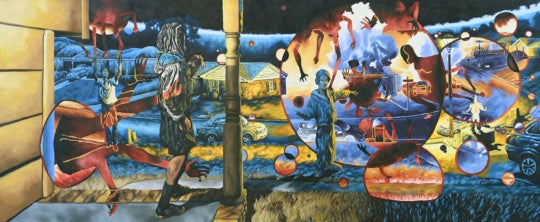

Erlanger’s short film Appliance (2024) follows the physical and psychological exchange between a woman, Sophie, and a house she recently inhabited. She is surrounded by all sorts of domestic technology—the appliances that became the standard of living in the same decade as the Skylab program. She merges with the interior through bizarre occurrences, and the appliances become extensions of her psychophysiological state. Drop clothes and ladders symbolize a cycle of innovation and renovation. A reminder that our bodies are subject to a similar cycle arises when Sophie injects what is perhaps fertility drugs, semaglutide, steroids, PrEP, etc. A soundscape emanates from the living room setting where visitors watch Appliance is filled with ominous weather forecasts, whirring and humming, and an unsettlingly familiar yet generic thriller-like movie score. Her house is metaphorically both a pressure cooker and a spaceship; fittingly, the looped video’s opening sequence is a countdown timer.

T plus 1

We might imagine how at least three infrastructures are active forms in orbit by placing the construction of Houston’s Space City identity in dialogue with If Today Were Tomorrow. First, the American dream and frontier mythology are ideological infrastructures that shaped federal spending and business investment policy during the Space Race and how Americans framed aspirational and speculative investing. Second are existing and new physical infrastructures—pipelines, airports, resource extraction—(partly) informed the decision to select Houston as the “nerve center” of NASA, explosive suburban growth across the US, and social ramifications delineated by suburban life. Third, technological infrastructures were designed to improve the quality of life through mass consumerism. This was part of the social engineering during the Space Age—systematically integrating technology through social conditioning. Olivia Erlanger: If Today Were Tomorrow and its temporary home in Houston provide a locational, historical-dependent response to her own inquiry regarding infrastructure decisions, identity, and disposition. An entire system with various objects and infrastructures interacting in general, albeit dynamic, regularity could allow for different timescales to be read together and recognize how diverse objects can be analyzed through the orbits of multiple infrastructures. Infrastructure shapes the construction of an identity, just as an identity informs infrastructural design.

[1] Olivia Erlanger and Keller Easterling, “Space as a Reflection of the Mind:,” Flash Art, March 10, 2022, https://flash—art.com/article/space-as-a-reflection-of-the-mind/.

[2] Oliver Erlanger: If Today Were Tomorrow (Houston, Texas: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2024).

[3] Linda Billings, “Overview: Ideology, Advocacy, and Spaceflight—Evolution of a Cultural Narrative,” essay, in Societal Impact of Spaceflight, ed. Roger D. Launius and Steven J. Dick (Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of External Relations, History Division, 2007), 495.

[4] Stephen B. Oates, “NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston, Texas,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 67, no. 3 (1964): 374.

[5] Caldwell C. Johnson, tech., SKYLAB EXPERIMENT M487 HABITABILITY/CREW QUARTERS (Houston, Texas: Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, 1975).[6] In 1973, at CAMH, the artist collective Ant Farm streamed a live video feed from Skylab in their installation Living Room for the Future, part of their exhibition 2020 Vision.