notes towards becoming a spill, a new installation by Shikeith at Atlanta Contemporary curated by Aaron Levi Garvey of Long Road Projects, restructures space and slows time. This installation evokes both the material and the immaterial to create a vacuum where the healing of Black men is possible.

Light pours from the ceiling, melding with the sounds of Black men’s voices “spilling truths.” The curved walls and bending light create a feeling of movement and instability as the voices of anonymous men share their fears, pains, hopes, and joys—dating, sexuality, and mental health fall on the ears like a laying on of the hands. Shikeith probes the internal, calling for introspection, reverence, and the archiving of Black male existence.

TK Smith sat down with Shikeith to talk about the installation before it closes at Atlanta Contemporary Art Center on April 21, 2019. Their conversation has been edited for publication.

TK Smith:I was curious if notes towards becoming a spillwas visually, physically, sonically created with the Atlanta Contemporary, or the South in mind?

Shikeith: I wasn’t making it with the Atlanta Contemporary in mind, but I do think about the South. The South has been this place that I’ve been going, mostly geographically, but then also symbolically. I’ve been making a lot of work that references a lot of materiality or material that comes from the South, like the haint-blue paint.

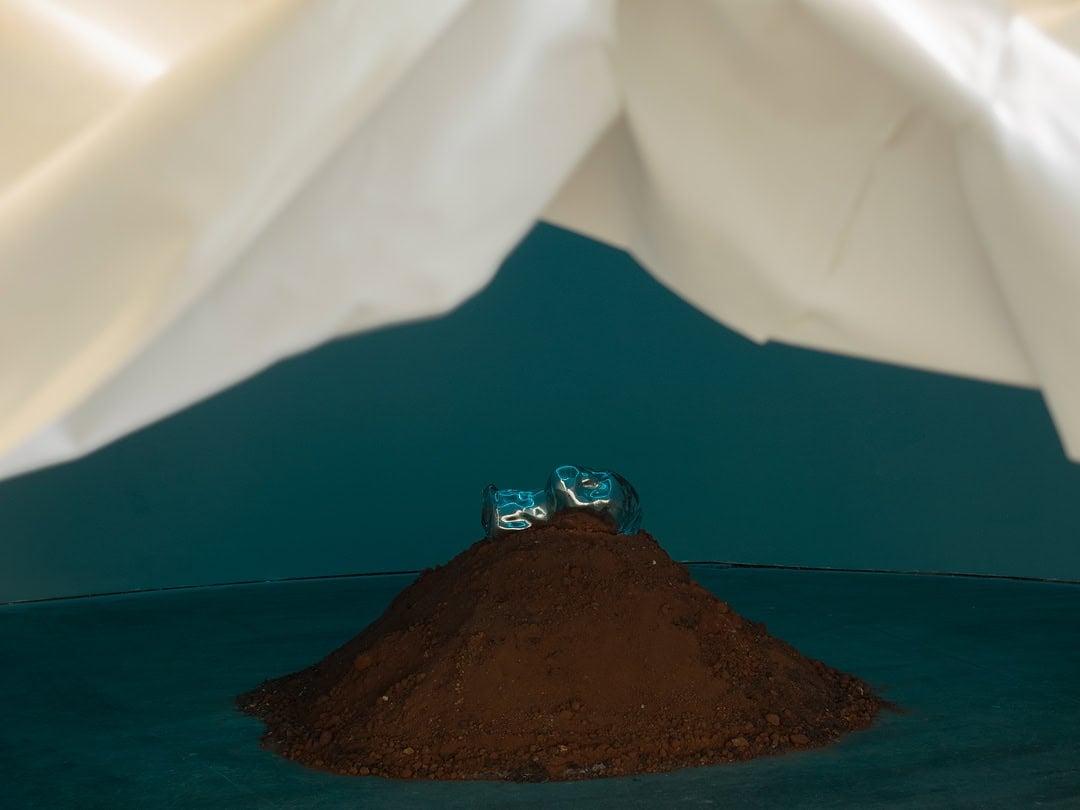

This is the first time this work was created and produced [incorporating] that Georgia red dirt. I had always known I wanted to implement or incorporate soil into the work just because of my thoughts around cultivation; cultivating space, potentiality, and soil being a material that spoke that language. The decision was made while installing, not to get generic soil from Home Depot, but to dig it up from the charged land in which the installation existed.

TKS: I should say I’m not from Atlanta. I should also say that I’m not from the South. I’m from Iowa. Atlanta is a growing city with a lot of transplants. Even though the city is considered this Black gay mecca, I have found it very hard, as a Black queer man, to find community. A space like this for me is unique and a real a necessity.

I had a conversation with a photographer about the installation being a space specifically for Black queer men. Where I saw the work as a space, he saw the installation as a photograph.

Shikeith: I like that sort of oscillation. It’s funny that one dude thought of it as a photograph. Photography is my background, like my core sort of foundation, so I am always thinking about generating an image. But for this particular installation my sort of challenge to myself was how do I generate an image through absence?

I also was also thinking of space as a document, particularly for us. Accounts of our experiences have been kept underground, so this is a work of excavation, archiving, making known, and revising. This is space as a cathartic experience.

TKS: In the material vernacular you’re creating, what materials do you find yourself returning to? What meanings have you ascribed to certain materials that didn’t exist before?

Shikeith: The materials that recur are soil, glass, breath, clay, and the ghost-tricking, haint-blue color of the Gullah Geechee. Respectively, each material carries its own histories and symbolism which later get remixed into this big pot of psychological gumbo. My use of haint-blue has become an obsession as it indicates the methodologies Black people invented to render reconciliation through materiality and form. Also, glass is a material I began ascribing new meaning during an incubator at the Pittsburgh Glass Center. For me, glass is a Black queer material because it is unfixed from categorization and exceeds representation. It is neither a solid, liquid, or gas, but its own state of matter resisting a static place in the world. Glass, to me, signifies the embodiment of Black manhood that is on boundless trajectories.

TKS: Sometimes I don’t feel so boundless in America, sometimes I don’t feel so boundless in my Blackness, sometimes I don’t feel so boundless in my manhood. If you were to create a space that was to take into consideration the confines of socialization, what form would that take visually or physically?

Shikeith: The first thing that came up, as far as form, is a spill. A spill is an anti-form and so it does its own thing. That’s something I’m exploring; how can I construct spaces that embody this boundlessness?

That’s also where my series of blue spaces emerge from. It’s not just one space, it’s two spaces, three spaces, four spaces, five spaces. Allowing this metamorphosis to take place within this constellation of artwork, I am revising content as well as notions of Black manhood. I am revising objects and the way they exist across multiple artworks. I feel that’s how I get towards this spill or boundless visualization of Black masculinity, at least in space, content, and form.

TKS: I’m curious what you would say about manhood in a queer context? Does the queering of manhood transform it, is it something very familiar that we don’t recognize?

Shikeith: Actually, there’s an author named Mark Anthony Neal, he published a book called Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities. He’s someone who I gained the language from in regard to a queering of Black masculinity. He talks about being bound to legible forms of Black masculinity that exist within the public consciousness. These are the historic constructions of Black male identity that emerged during and in the aftermath of American chattel slavery, Jim Crow, and so forth, which were imagined through the white patriarchy. Neal proposes rendering what was illegible, legible to illustrate the many ways Black men can and have operated in the world. So, by queering what we have learned to be “Black manhood” we get closer to the true essence of who we are. And, for me, within Black male culture we have always, already disrupted this in so many ways.

As an artist commentating on these issues, what I want to do with my work is allow the act of truth telling or being vulnerable to be a part of that transformation. We can do away with all we have come to accept as “a man”, as far as I am concerned. It comes with a history rooted in incompletion where it does not allow for us to be our full selves.

TKS: In the same vein of “spilling truths” can you talk about your thoughts on truth and how it can heal?

Shikeith: To tell the truth, is a freeing act. Witnessing Black men spilling their truths is restorative justice. As people still restrained by the historical constructions of being a Black man, involving the many truths of our existences was imperative. Since 2014, I have periodically recorded audio and video of Black men revealing their truths, with the intent of building an archive that not only valued our voices but sustains them.

TKS: What do you hope these sites do for Black men in particular?

Shikeith: If you visit each, you will see objects move from screen space to real space or colors emitted through video projections shift to painted walls or bodily flesh. It is the process of becoming malleable that drives these installations, it is embedded in there most importantly for Black men to witness. I want Black men to gain intellectual enlightenment in these spaces just as much as I want them to imagine, sweat, and dance inside. I’ll create them for as long as necessary.

TKS: You mention your show coming up in Miami. Can you speak on that project a little and how that project intersects with this one?

Shikeith: The work is entitled the language must not sweat, it thinks through the interior worlds of Black men by way of a dream-like landscape; what we’re studying, contemplating, and how we are functioning underneath it all.

“The language must not sweat” actually comes from the writer Toni Morrison. [She speaks on] how writers should allow their language to do its own thing, be effortless. This installation thinks about that through the slippage that occurs at the intersections of queerness and Black masculinity.

TKS: Your titles are so beautiful and extremely poetic. I wanted to close by asking you to speak more on the process of naming your work.

Shikeith: The [titles] all sort of represent poetry, one of my favorite poets is Rickey Laurentiis, who is a very dear friend. They have helped me to open up the language in a way that is meaningful. [They have pushed me] to think about how words or titles can support the artwork. And so, all these titles, notes towards become a spill, the language must not sweat, to bath a mirror, these are acts I’m thinking about. These sort of fantastical acts that are occurring within the space but also within the language that is used to name it. Naming spaces, to name them is such an important part of the process and so I want my titles to be as effective as the actual artwork. I mean my name is Shikeith, I’m going to give you something deep.