In 1801—following the interruption caused by the French Revolution, during which he fought alongside revolutionaries to defend his native Lyon—Joseph-Marie Jacquard returned to the idea for an automated loom that had first occurred to him a decade earlier. Using a system of interchangeable punched cards arranged in a certain sequence, the device invented by Jacquard allowed for looms to create complex patterns automatically. (Silk weavers, fearful of losing their jobs to automation, did not take to the invention kindly, burning machines and attacking Jacquard himself.) Eleven-thousand Jacquard looms were in use in France by 1812, quickly spreading to England, then the rest of the world. Jacquard’s curious “chain of cards” was incorporated into the design of the “analytical engine” proposed by English inventor Charles Babbage in 1837 and is now considered a pivotal contribution to the history of computing hardware, an early nineteenth-century ancestor of the computer you’re using now to read these words.

Over 150 years later and 4,000 miles away from Jacquard’s Lyon, over 800,000 African American men gathered on and around the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in October 1995, answering Louis Farrakhan’s call for a Million Man March meant to “convey to the world a vastly different picture of the Black male.” Of the many pictures—actual photographs—documenting the march, one of the most iconic images shows the upraised hands of a crowd of men, not quite the raised fists of Black Power, many hands palms-up as though in salute or praise. A year earlier, as a young curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Thelma Golden had organized Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, an exhibition of works that were, in Golden’s words, “united through their interrogations of Black masculinity” [1]. Glenn Ligon, one of the artists whose work was included in Black Male, would later appropriate the image of upraised hands at the Million Man March in his 1996 work Hands. When Hands was prominently featured in Ligon’s 2011 retrospective AMERICA at the Whitney, the artist told NPR, “I took a very small image and blew it up to enormous scale. What happens when you do that is that the information in the image starts to become indistinct. The image darkens… becomes more ambiguous” [2]. Writing about the work in Hyperallergic that same year, Rachel Weltzer described Hands as “a copy of a copy of a copy, an image that can no longer articulate what it once represented” [3].

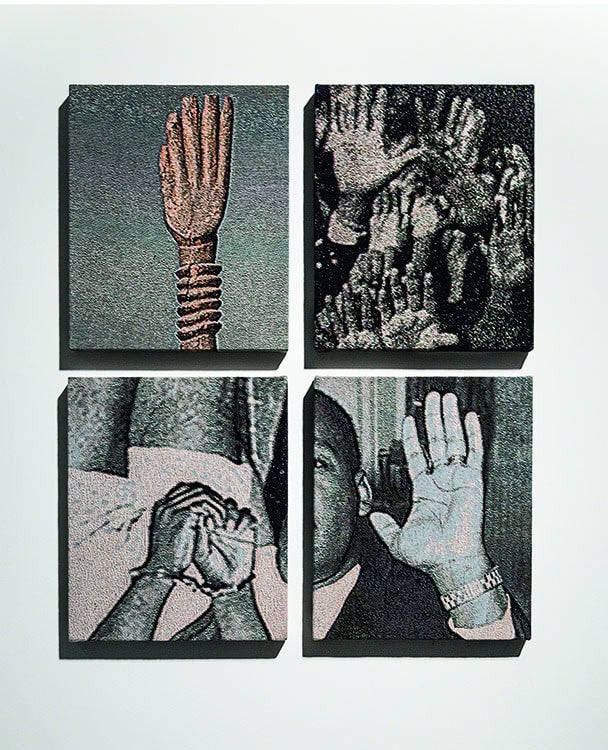

In artist Noel W. Anderson’s Hands-Up (2016), these superficially disparate threads of history—the nineteenth-century textile genealogy of computing technology and the visual archive of Black Americans’ struggles for political and cultural empowerment—are irrevocably intertwined, impossibly interwoven, stretched apart and knotted together. In four stretched Jacquard tapestries arranged in a two-by-two grid, Anderson shows four images of Black figures’ hands raised, including a cropped portion of the photograph from the Million Man March previously used by Ligon twenty years earlier. The three other images are similarly culled from the vast archive of Black visual history: the raised left hand of Martin Luther King, Jr., recognizable although only a portion of his face is visible; an anonymous man’s handcuffed wrists, his hands paradoxically raised because the image has been vertically flipped; and, closely cropped, the stylized hand of a traditional African sculpture. For contemporary viewers, of course, the work’s title runs another thread through each of these images, words that invoke tense, sometimes fatal standoffs between police and Black Americans, particularly protestors involved with the Black Lives Matter movement. Hands-up: the gesture and all it conveys—surrender and exaltation, devotion and defense—reverberate in these images, creating a visceral, low echo in the viewer’s mind. A copy of a copy of a copy, indeed.

Anderson’s embrace of Jacquard tapestries as the medium for these sort of conceptual excavations could hardly be any more intellectually or materially satisfying, creating images whose cropped, slightly ragged visual quality evokes digital photo files, using the very same technology that preceded modern computers. While Hands-Up employs juxtaposition across space and time to distill the gesture’s multivalence, other works in Anderson’s Blak Origin Moment—his solo exhibition on view at the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga through January 12—apply classic Minimalist techniques such as seriality and repetition to woven versions of found photographs and images from decades-old issues of Ebony magazine. In his series The Sportsman (2016 – 2017), Anderson takes an archival image of a Black man from Ebony, originally used to advertise hair products and a hairstyle of the same name, reworking it across five Jacquard tapestries. In one, the tapestry has been stretched so that the image is wavily distorted, layers of thread picked apart and tattered, as though appearing on a grainy television. In other tapestries in the series, the same image is modified with paint or fabric dyes, rendering the man’s face slightly differently each time: once streaked as though with bleach, and, in another, his face painted over with ghastly white brushstrokes, his hair a putrid yellow.

As much as Anderson confronts physical acts of racial violence—several works in the exhibition address police shootings of unarmed Black individuals directly—his photo-tapestries display a particular concern with technology’s role in mediating perceptions of Black identity and personhood, affirming artist and critic Aria Dean’s claim in her 2016 essay “Rich Meme, Poor Meme” that “[Black] people… are no strangers to the alienation of a mediated selfhood” [4]. While discussing the prevalence of images of Black people across social media and especially in memes, Dean also notes “the aggressive circulation of videos of Black death or violence against Black people in general,” a phenomenon also implicitly mirrored and critiqued in Anderson’s virally repetitive photo-tapestries. Dean’s essay is itself partially a response to, or perhaps an elaboration upon, certain points raised in Hito Steyerl’s earlier essay “In Defense of the Poor Image” (2009), another critical text with special relevance to Anderson’s Jacquard works [5]. Steyerl describes the poor image as “a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail… a rag or a rip; an AVI or a JPEG, a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances.” Anderson’s poor images, however, have been impoverished not only by the “countless transfers and reformattings” Steyerl describes but also by the violence of the white gaze present in most mainstream channels of semiotic distribution.

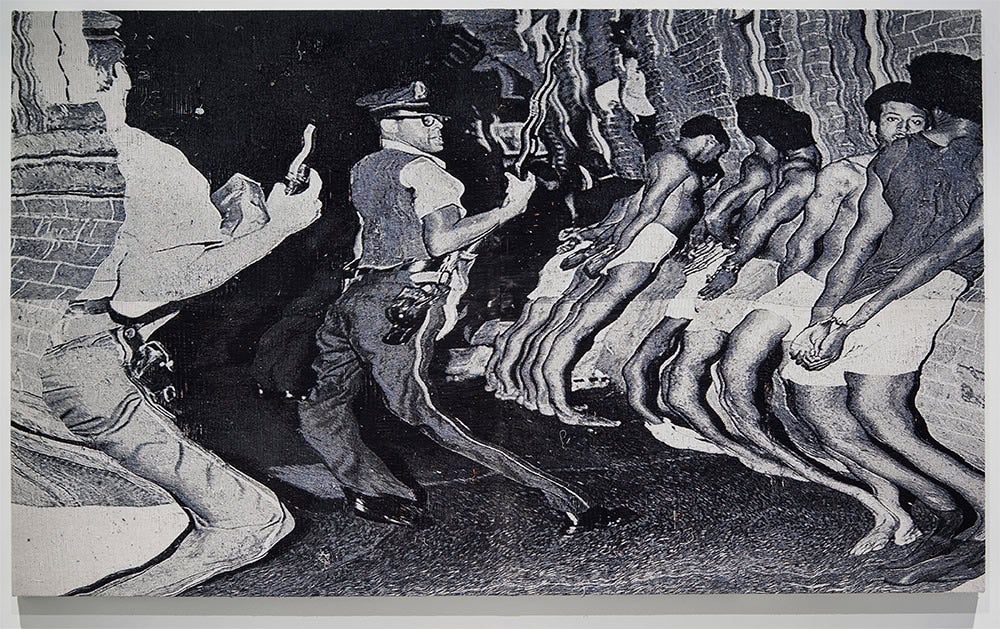

Anderson’s particular genius in Blak Origin Moment is materializing these poor images as glitch tapestries, lifting infinitely malleable pixels into concrete space and revealing the remarkably close proximity between textiles and digital art. (An additional, virtually exponential factor of Anderson’s choice of the textile medium is its widespread association with Black women’s artistic traditions, a connection he honors and subverts here.) Elsewhere in Blak Origin Moment, this deft reconciliation of mediums achieves the monumental scale of history painting. This is particularly true in Anderson’s Die Lietung (2016), which shows a black-and-white image of a lineup of Black men being forcibly strip searched by armed white policeman, presumably from a 1960s-era newspaper photograph or television image. In the tapestry, which stretches thirteen feet wide, the picture blurs so that the row of Black men’s legs swoop leftward, creating a repeating shape that distorts the remainder of the image, including the bodies and raised weapons of the policemen.

Beyond his Jacquard tapestries, which are without a doubt the chief reward of Blak Origin Moment, Anderson continues to demonstrate his skill as a collagist of appropriated materials elsewhere in the exhibition, which additionally includes a former police barrier and a German doll portraying racist stereotypes suspended on the gallery walls, installed as quasi-found sculpture. In the video work STOOR, afforded its own darkly velveteen gallery at the Hunter, Anderson reverses the audio and video of the 1977 television adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots, visually undoing the history of slavery and distorting the language of the narrative beyond recognition. This conceptual gesture is both earnest and arch, reproducing but picking apart the images and sounds of Blackness the artist has inherited. To this end, Anderson’s works are united in purpose. The word ravel—more familiar in its opposite form, to unravel—means both to tangle and untangle, to simultaneously refine and complicate, and this is precisely what Anderson does to conventional images of Blackness.

Noel W. Anderson: Blak Origin Moment is on view at the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, Tennessee, through January 12.

[1] Artforum, Summer 2016, 141-142.

[2] npr.org, May 8, 2011.

[3] Hyperallergic, May 3, 2011.

[4] Real Life, July 25, 2016.

[5] e-flux, November 2009.