This artist project contains hidden captions which are toggled by mousing over the images.

Audre Lorde stated, “In our work and in our living, we must recognize that difference is a reason for celebration and growth, rather than a reason for destruction.”

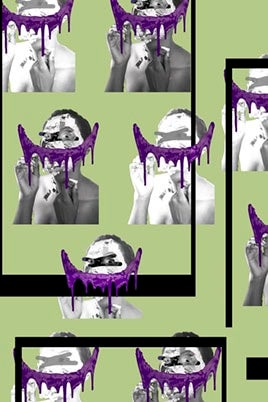

America is in the midst of a societal awakening, and as someone who has been a victim of the very systems being fought, I feel a duty to participate and use my voice. I have shared the stories of others as well as my own, protested in the street, and stood in line to cast my vote. In my art practice, in works such as Tainted Smile and The Proverbial Ankle Bracelet, I use strong contrast and strange configurations to depict the sharp bitterness of my own lived experiences as a Black woman and bring attention to the oppressive systems that impact those experiences.

“It reminded me that, even though this was the place I was born and raised, because I was Black, I was considered a tourist—a foreign language from a distant land that seemed irrelevant and unnecessary to learn.”

from What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair?

Alexis Childress, The Proverbial Ankle Bracelet, 2021.

“It reminded me that, even though this was the place I was born and raised, because I was Black, I was considered a tourist—a foreign language from a distant land that seemed irrelevant and unnecessary to learn.”

from What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair?

Alexis Childress, The Proverbial Ankle Bracelet, 2021.

One of the most powerful influences that disturb society’s perception of dark skin is underrepresentation and biased stereotypes in the media. The deficiency of Black presence in media creates cultural barriers between races while supporting colorism; a term defined by Kaitlyn Greenridge as a “prejudice based on skin tone, usually with a marked preference for lighter-skinned people”—a root cause of the racial profiling we see today.[1] In recent years, the conversation of underrepresentation has inevitably been brought to the table as Black people all over the country are dealing with the effects from decades of media partialities.

“This adolescent encounter fed on the internalized white supremacy that has infected Black people across generations. An infection that convinced me to feel lesser than her because my skin was darker, and my hair did not look like hers.”

from What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair?

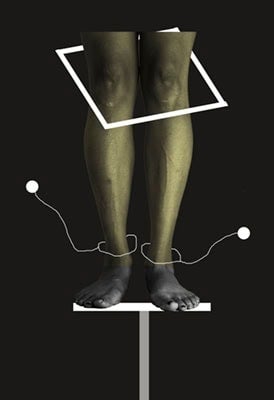

Alexis Childress, One Foot In Front of the Other, 2021.

“This adolescent encounter fed on the internalized white supremacy that has infected Black people across generations. An infection that convinced me to feel lesser than her because my skin was darker, and my hair did not look like hers.”

from What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair?

Alexis Childress, One Foot In Front of the Other, 2021.

Visualizing my experiences with these effects, The Invasion of Everything depicts the feeling of being conquered by negative influences and bizarre convictions. The colorful carrot assumes a pop culture informed sexual connotation, while soldier-like white triangles embody the spirit of danger, aggression, and relentlessness. In my piece One Foot in Front of the Other, the blue paint drips act like water, slithering down feet just as the struggles of our ancestors have crept through time. The ripples in the feet act as fossils symbolizing a treacherous journey and reminder there has never been a generation of Black people in America that was free, not targeted in any way, and given true equal opportunity.

“From the perspective of a black girl in the 7th grade, raised in a white community, this moment was an echo of my insecurities and exceeded the expectations of embarrassment. For me, this confrontation of racial differences became a moment of reinforced inferiority, acting as a souvenir of my reduced place in our community.”

from What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair?

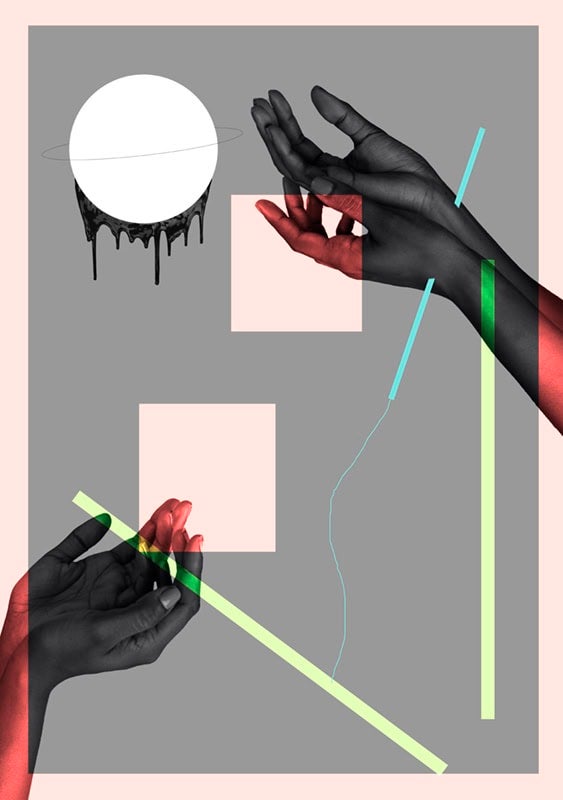

Alexis Childress, I Would Die for Straight Hair, 2019.

“From the perspective of a black girl in the 7th grade, raised in a white community, this moment was an echo of my insecurities and exceeded the expectations of embarrassment. For me, this confrontation of racial differences became a moment of reinforced inferiority, acting as a souvenir of my reduced place in our community.”

from What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair?

Alexis Childress, I Would Die for Straight Hair, 2019.

In my college thesis essay What Do You Know About Black Girls’ Hair? I was forced to confront deeper issues of self-perception and identity I developed while growing up in white America. The essay converges on a moment in the 7th grade when a white girl asked me if she could touch my hair. A moment that did not cause harm to my physical body yet became a lasting addition to the inferiority complexes that followed me into adulthood. In this instance it became clear that racial biases in media played a major role in creating a complex for, not only those around me, but also for myself. In my work I Would Die for Straight Hair, I depicted a scene, layered atop a collage of hair straightening products, where I tore my head off my body to pull my hair as straight as possible; creating a visual representation of the intense anxiety I felt about having thick, kinky hair. In high school, I would have died if it meant my corpse would have had straight beautiful hair like a white girl. In a world where I did not see many examples of Black women being portrayed in the media as strong and beautiful—while at the same time grappling with racially charged encounters—I developed a complex that told me because my skin was dark and my hair was thick, I was ugly. Authors Sosoo, Bernard and Neblett suggest:

While black students are exploring and making sense of their identity, they are also navigating unique stressors that may lead to the internalization of negative race-related messages and detract from positive psychological development …This is especially important to consider for Black emerging adults attending predominantly white institutions who must contend with race-related stressors (e.g., negative stereotypes) within settings in which they are underrepresented.[2]

I remember realizing at a young age that because I was a Black girl, boys, society and even others in the Black community would find me less attractive. I do not claim to have never been called pretty or attractive, but the compliment has many times been followed by “for a Black girl”—a phrase that is subtle and naive but always seems to strike deep. When “for a Black girl” is added to a compliment I take that to mean Black beauty cannot meet the standards of white beauty. That no matter how beautiful or perfect I try to be, my beauty can only be measured on the scale of Black women; a scale that only starts where white beauty ends.

Even outside of my hometown I was graded on this strange scale of beauty. While living in Myrtle Beach, I was once told by a white man that I was the most beautiful Black girl on the beach. A statement that I wanted so badly to take as a compliment but somehow still holds a sinister connotation when I recall it.

Why is a Black girls’ beauty bound by her skin color?

How much does the underrepresentation of Black women in media feed into this scale of beauty?

Alexis Childress, Passing Traditions, 2021.

Alexis Childress, Invasion of Everything, 2021.

“Being a black woman? I instantly thought of being scared. Protecting my child, being a great mother. Some people have never experienced being the only black person in the room… we’ve come so far yet are so far from where we need to be.” —Jazmyn Childress (Sister)

Alexis Childress, I’ll Get It When I Need It, 2021.

“Being a black woman? I instantly thought of being scared. Protecting my child, being a great mother. Some people have never experienced being the only black person in the room… we’ve come so far yet are so far from where we need to be.” —Jazmyn Childress (Sister)

Alexis Childress, I’ll Get It When I Need It, 2021.

It has been hopeful to see how representation in the media has progressed in the last several years, focusing on diversity and finally taking the portrayal of complex Black female characters seriously. My art practice typically addresses the adverse racial barriers and systems that infect American culture; However I find myself needing to step away from looking at the negative and focus on the positive. While watching the HBO series “Lovecraft Country” I was inspired by the character Hippolyta and her sci-fi journey through time and space, simultaneously existing as many versions of herself. Aligning with my Afrofuturistic aesthetic, I knew I wanted to make a body of work inspired by my ancestors and my own curious journey through time.

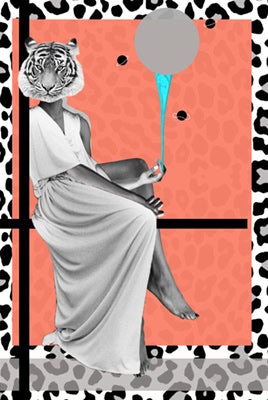

I have chosen to celebrate the Black matriarchal tradition and employ a retro-futuristic approach to define my identity, combat media fed racial typecasts and uplift the defiant feminine strength of Black women. I combine found imagery, digital marks and shapes, photographs of my body as well as photographed analog paint marks to create surreal characters and seductive scenes that are not bound by labels, profiles, or time. In works like I’ll Get It When I Need It and Disco Queen, I use the female form and varying textures to respectively reclaim my own sexuality and femininity. In Huntress and Endangered Species, I am exploiting animal print, sharp points and hard lines to exert power and confidence. Redefining the stereotype of a fierce Black woman. Through my current work I hope to aid in dismantling fabricated barriers and promote the idea of leaving a legacy better than we were given.

I spent many years reveling in inferiority and at one point accepted myself as a victim, but today, my voice sings no victim’s song.

“I am an endangered species, but I sing no victim’s song. I am a woman. I am an artist. And I know where my voice belongs…”

–Dianne Reeves

Alexis Childress, Endangered Species, 2021.

“I am an endangered species, but I sing no victim’s song. I am a woman. I am an artist. And I know where my voice belongs…”

–Dianne Reeves

Alexis Childress, Endangered Species, 2021.

Growing up I watched my grandmother be the glue of our entire family while slowly losing her husband who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. I watched my mother ascend from dark times, raise two girls on her own and then go on to successfully start her own business. I watched my two aunties live as best friends and teach me that the bond of sisters can never be replaced. I watched my own sister gracefully take on being a young mother, making it look effortless when I know raising a child requires immense focus. And this past December I watched every one of these women hold their head high as we came together and said goodbye to one of my aunts. Absorbing the stories of the women that raised me gave me the strength I needed to survive a world that was not made for me. As society pushes forward, I continue to put one foot in front of the other. Through the endurance of matriarchal legacy, I inherited wisdom, perseverance, faith and elegance. Allowing me to live with absolute certainty I can make a difference, I can survive anything, and I am no victim.

“When I was starting my own business, I found resources to grow your business for Native American, Veterans, LGBT but not Black women. When you’re a black woman your opportunities are limited. I had to learn that wasn’t true and I had to believe in God to get my strength, and then believe in myself.” —Demetria Stafford (Mother)

Alexis Childress, Huntress, 2021.

“When I was starting my own business, I found resources to grow your business for Native American, Veterans, LGBT but not Black women. When you’re a black woman your opportunities are limited. I had to learn that wasn’t true and I had to believe in God to get my strength, and then believe in myself.” —Demetria Stafford (Mother)

Alexis Childress, Huntress, 2021.

I am Black. I am a woman that is Black.

I am strong. I am fierce. I do not lack.

I am complex. I am loved. I am brave. I am free.

I am my aunt. I am my mother. I am my sister.

And I thank God they are me.

[1] Kaitlyn Greenridge. “Why Black People Discriminate Among Ourselves: The Toxic Legacy of Colorism.” The Guardian, 2019.

[2]Sosoo, Effua E, Donte L Bernard, and Enrique W. Jr Neblett. “The Influence of Internalized Racism on the Relationship Between Discrimination and Anxiety.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 2019.