For the first installment in our new artist column Mood Ring, Brian Hitselberger writes about hate speech, queer hypervisibility, and the drag performance that inspired his current work.

Central to everything I am and believe and have written is my astonishment, naïve as it seems to people, that you can use human speech both to bless, to love, to build, to forgive and also to torture, to hate, to destroy and to annihilate.

ADVERTISEMENT— George Steiner [1]

This is an essay about the word faggot, a word used to hate and to bless, depending upon its speaker and context. This is an essay, and hence it is made of words—my hope is that these words forgive and destroy in equal measure.

Almost a decade ago, I came across a video on YouTube of a pre-Drag Race Detox Icunt performing in a small club to Larry Tee’s “Get Off Your Ass.” Over the years, I’ve watched it every time I’ve been called “faggot” by a stranger from a car window or on the street, and I’ve sent it to my friends every time this happens to them. This is another way of saying that over the years I’ve watched it a lot.

It is a mesmerizing work of art. In the four-minute video, Detox appears out of the darkness wearing a foot-high wig and a brilliant red, low cut evening gown (complete with enormous Dynasty-era shoulder pads). Greeted by reverb, a drum machine, and the screams of a crowd that remains almost exclusively off camera, she begins her routine by counting off in Spanish while a relentless spotlight alternately reveals and erases the contours of her incredible face. Somewhere around the forty-second mark, she points a finger directly at the owner of the phone recording the whole show—and, by extension, at all of us behind our screens—and earnestly shrieks the question, “Who you calling a faggot!?”

The remaining three-and-a-half minutes are pure transcendence, with the queen moving up and across her stage in huge graceful strides, at once totally poised and wildly erratic. Her smile shifts between the libidinous grin of a sex goddess and the gaping maw of a cannibal. Her limbs move with a violence that almost obscures their studied choreography—she is, after all, a professional. By the time she repeats her question around the 2:58 mark, I feel like I’ve witnessed a queer shaman who has conjured the seemingly impossible: a life completely without shame.

That moment when her question is repeated—Who you calling a faggot!?—always leaves me giddy and lightheaded, like I’ve witnessed a magic trick at close range. In fact, this is exactly what has happened: she’s taken speech used to hate and made it into speech used to bless right before our eyes. She dons her ceremonial garb, enters into a trance state of focus, performs a ritualized set of movements, and turns lead into gold. She teaches by example; she “gives me life.” The second time she asks us, we of course already know the answer: she’s been called a faggot, and she makes it look like the greatest fucking thing in the world.

In her book Citizen: An American Lyric, poet Claudia Rankine describes a moment where she found herself

“…in a room where someone asks the philosopher Judith Butler what makes language hurtful…. Our very being exposes us to the address of another, she answers. We suffer from the condition of being addressable. Our emotional openness, she adds, is carried by our addressability. Language navigates this. For so long, you thought the ambition of racist language was to denigrate and erase you as a person. After considering Butler’s remarks, you begin to understand yourself as rendered hypervisible in the face of such language acts. Language that feels hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present. Your alertness, your openness, and your desire to engage actually demand your presence, your looking up, your talking back, and, as insane as it is, saying please.” [2]

The language of homophobia is, of course, not the language of racism, but I share Rankine’s sentiments regarding its supposed ambitions “to denigrate and erase you as a person.” I also share Butler’s conviction that “we suffer from the condition of being addressable,” particularly when the way in which we are addressed is intended to overwrite or obliterate our sense of self with the bigoted perceptions of those doing the addressing (as in, “Hey faggot!”). This notion of being “rendered hypervisible” is the mechanism Detox turns on its head in her performance. Hate speech of all kinds indeed exploits the ways in which we are present, but as Detox shows us through her blazing presentness, your own hypervisibility can transform speech itself. She fills the stage, the room, the eye, the mind. She makes a furious red spectacle of her hunger. She licks her lips and swallows whole all the space shame once sought to occupy. She does not say please.

At its core, hate speech is born from the triumvirate desire to create a distance, to devalue, and to mediate the speaker’s fears. I much prefer to imagine hate as fear’s long shadow because this allows me to watch it wither and vanish under a spotlight while a fierce queen flips her wig and spits on the ground. Judging from the cries of the crowd, I am not alone in feeling this way.

I am not alone.

“Queer people are the only minority whose culture is not transmitted within the [biological] family,” writes artist Nayland Blake. “The extremely provisional nature of queer culture is the thing that makes its transmission so fragile.” [3] (“Fragile” is not a word I would use to describe this particular artifact of queer culture, although I see Blake’s larger point here.) Like anyone, queer people learn by example, and we take those examples where we can find them.

For as long as I can remember, I have been hypervigilant in seeking echoes of my own queer interior life in the words, actions, and movements of others. When I heard one of these echoes (on television, in literature, in art) I felt myself recognized, validated—I did not feel alone. This tendency was especially acute in adolescence, when my sense of isolation was at its strongest. Unsurprisingly, this is also the period when I developed relationships to certain pieces of art and media that I can now say, in adulthood, have been foundational to the development of my aesthetic sensibilities. These were the objects and people that made me feel safe—a kind of a found family.

When I say that I find this performance astonishing, it is because I see inside it a power I crave in my own life and in my own work. To be astonished is to crave, to crave is to desire. And to desire is, of course, to be human. The gravitas of such a simple formula is not lost on a queer person who has been told again and again that their desires place them outside of humanity. Given these conditions, is it at all surprising that such a furious and hungry spectacle elicits euphoria from a crowd in the dark? Or that a drag queen in a ten-year old YouTube video has become a kind of spiritual healer for me, someone to show me what is possible?

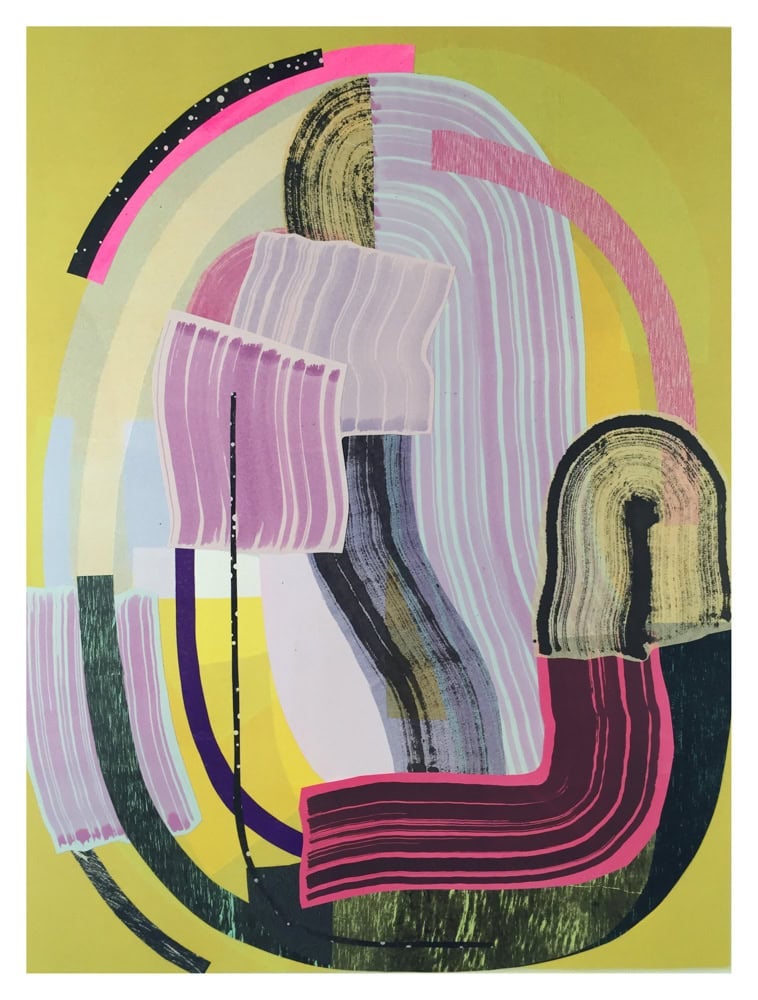

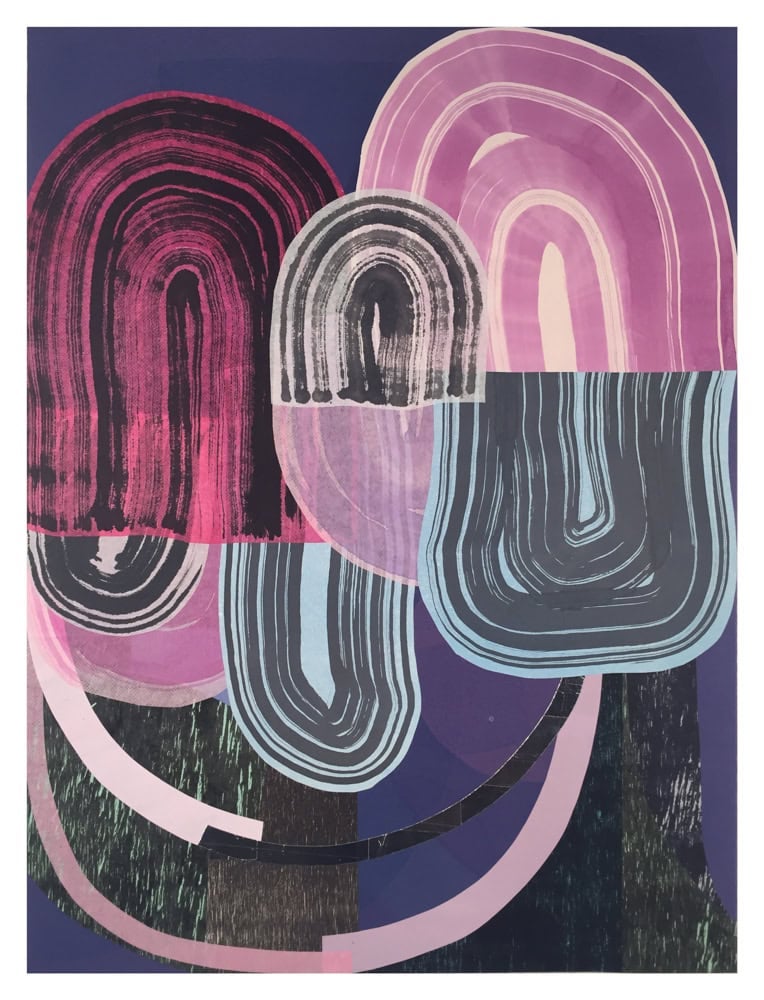

My recent work aspires to not only describe this healing but to recast it in other forms. The shapes, directional forces, lines, and colors in these prints and collages come directly out of this performance: documents of the dance without the dancer. This absence is notable. Without the face or body of the performer in these images, a viewer is permitted to inhabit their energy. The collage process—the literal removal of an element from one context and placement of it into another—seemed especially apropos for this project, as this is more or less a description of how I have constructed my own queerness over the course of my life, and how Detox, through the art of drag, alchemizes of the language of hate speech. There is great power in this willful fluidity of language and in an intoxicating disregard for boundaries’ rigidity. To name it directly would be a disservice; I’d rather render it visually, so that it might be claimed by another. After all, this is what Detox has done for me.

[1] From D. J. R. Bruckner’s “Talk with George Steiner,” The New York Times, May 2, 1982.

[2] From Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, published in 2014 by Graywolf Press. An earlier version of this quote can be found in a talk Rankine gave as a response to Tony Hoagland’s poem “The Change,” at the Associated Writing Programs Conference on February 4, 2011.

[3] From “Curating In a Different Light,” a curatorial essay by Blake to accompany the 1995 exhibition of the same name at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. A catalogue for the exhibition, with the text of Blake’s essay, was published in 1995 by City Lights Publishers.