If you appreciate the work we do to champion local art in Atlanta and the Southeast, please consider donating today. Your dollars ($) will count double ($$!) during BURNAWAY’s $15K Challenge matching grant from Possible Futures. Contributions of any amount are greatly appreciated. Your donations help us to continue to provide BURNAWAY as a free resource! You can make a donation here.

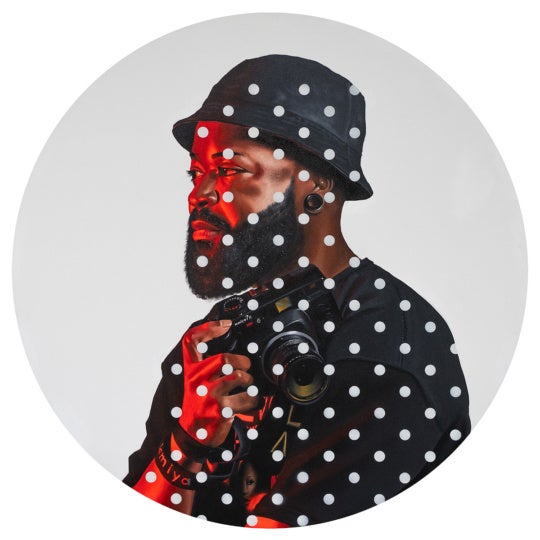

Kendall Buster is a sculptor whose work bears influences from her studies in microbiology and her fascination with the dynamics of architectural design. She is currently the Lamar Dodd Distinguished Professorial Chair at the Lamar Dodd School of Art at University of Georgia Athens. In her position as the Dodd Chair, she has spent this semester teaching students and developing an exhibition of new works. The show, Miniature Monumental, features models and drawings produced during her residency. Buster’s exhibition is on view in Gallery 307 at the Lamar Dodd School of Art Galleries through November 12.

Katie Geha: Explain the process of the exhibition a little. Was it influenced by your time at Lamar Dodd?

Kendall Buster: Well, I haven’t done anything like this in a really long time. I can just kind of go into a zone and work on what I think of as almost pure research. When you teach at a university, as you know, there are the big three—research, service, and teaching. Research is something that can be confusing because typically we think of it as your exhibition record or the papers you’ve published, and that’s certainly the product. But there’s a reason … “research” is still the key term, because all of that productivity is rooted in something that is really the foundation, [namely] the research. So, then, what is research? There’s this period of not exactly knowing where it’s going, allowing a certain amount of chance, a certain amount of openness and letting yourself to go into a territory that is a little bit unknown.

KG: And how did that time of research lead into this exhibition?

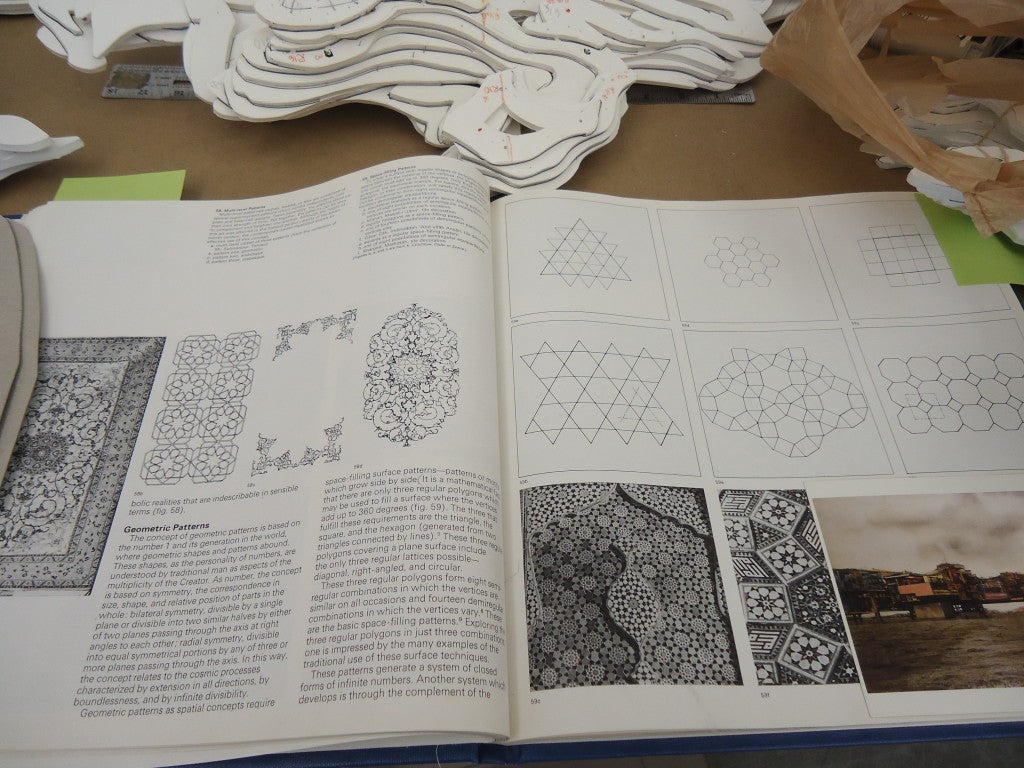

KB: It’s a combination of going into some things that are unknown, working with a process that is different from ways in which I have been working in the recent past, and a kind of returning to some earlier investigations. Just prior to coming here, I was finishing the production of a number of large-scale projects that are integrated into architecture and involve a lot of planning, engineering, and a pretty extensive fabrication process. My current studio activity is a return to some of the things that I was interested in quite a few years ago, and this occurs in two ways. The first is that it’s quite a formal way of working, planar constructions that are my way of getting back to basic principles of abstraction. Secondly, the forms themselves, maybe because of their strict planar elements, evoke spaces that are a little more sinister than the more biological forms I was working with in the past.

KG: In what way are they sinister?

KB: In terms of the kind of spaces I have been looking at, I have been interested in the ways in which architecture controls. Sure, it can be benign, but even if it’s a protective structure, like a fortress, there’s still something sinister. There [are] all kinds of wonderful dynamics in enclosure, in that it can offer at once a sense of protection and entrapment.

Another interest for me is that in architectural structures there is always a sense of looking and being looked at. In the dynamic of architecture as frame, there will always be power relations. Whether you are hidden or exposed. Certainly some of the models I’m looking at imply observation towers—one of them suggests a panopticon or a prison structure. Even the ones that appear to be stadiums operate in this way. Here, there’s a weird evocation of a modern-day coliseum, and I suppose you could say there’s something sinister about that, too!

KG: I know you’ve been sitting in on some classes at UGA this past semester. How has this course work influenced this project?

KB: I’m really fortunate to be at this university and to have the time to attend seminars. I’m attending a seminar taught by Dr. Ronald Bogue that is a careful reading of Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus. One day, Professor Bogue talked about the concept of faciality, and he showed us a wonderful image from a Giotto painting where all the buildings on this hill have these wonderful little windows. In the same way that Giotto’s paintings have an iconographic treatment—the windows are done in a skewed perspective, very generalized as cut-out, hollow places—there’s a wonderful sense that these windows are stand-ins for eyes. This just delighted me because this is exactly what happens with for me with these models. The outside shape of the forms operate as an abstract language so a viewer can access the plan through a birds-eye view. But there [are] also interior spaces, as well as the windows, that create a kind of sinister sense of what is lurking inside. They’re dark and yet there is a formal continuity of these cut-out holes. I found that to be an interesting connection.

KG: I wonder if the psyche of the sinister is stronger in relationship to the scale? Is the miniature related also to a more studio-based practice due to the time and space you’ve been given for this residency?

KB: What surprised me is that, for the last few years, the models I have made were projections for a larger piece and functioned in the ways one might traditionally think of model building: as a study for a larger architecture structure. I’ve realized in the studio that these models have a viability as completed art objects, and they’re not necessarily a step to something bigger. There’s something about the miniature, the way that it pulls you in. You have a much different relationship to that object in relation to your body. Also, I am intrigued with ways in which the miniature is so common to horror or magic tales. There’s a delight but also an uneasiness in the miniature.

What intrigues me about scale is its flexibility. At one point, working on the large sculptures, I was thinking of them as vessels that had gotten very large, and then you could walk into them in a kind of Alice in Wonderland way. And then, at one point, it occurred to me that, say, a 12-foot vessel could be a model, a very large model for a 12-story building. It was one of the first times I thought of these large pieces as also being models themselves. The idea is that scale is constantly under reconsideration, it’s a little provisional. Scale is not a stable index to a particular fixed size. It is something that’s always shifting, and in that same way your relationship to the work, the size of your own body, shifts. So, you might be very tiny in a massive structure, or you may have a birds-eye view, a simultaneous view of the work versus what would happen if you were walking through the city, which is a series of views in time. I’m interested in how a model can provide a sense of understanding of space.

KG: Would you say, then, that the models allow you to explore space, scale, and abstraction?

KB: Yes, each of these models represents a space. I’m still completely invested in the idea of the architectural model as a language in itself and how that converses with the history of geometric abstraction. This is a time for me to return to that [idea], and half the time I feel like I’m completely engaged in the pleasure of diving into these formal relationships, which is simple planar construction, and then on the other hand, in my own imagination, sliding back and forth into a kind of being in the spaces in my head.

Miniature Monumental is on view at the Lamar Dodd School of Art Galleries from October 24 through November 12. To learn more about the exhibition visit: http://art.uga.edu/galleries/gallery-307/

Katie Geha is the director of the Lamar Dodd School of Art Galleries.