It was late July, and this was how we wandered.

In the languid air that followed fitful rain, we commenced shoulder to shoulder, moving east on Thirty-second Street; concrete solid beneath our feet, vast sky overhead. We are about the same height, give or take a few centimeters, and I drew a keenly felt sense of camaraderie from our shared vantage, although he seemed guided by—and intimately attuned to—some impulse that I was not yet familiar with. He seemed at home with each step.

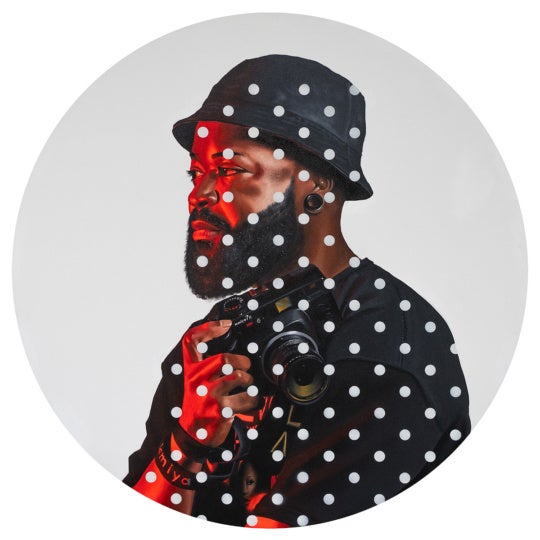

Walking is at the heart of the artist Adler Guerrier’s practice. His art springs from his walks along varying paths and trajectories and the sundry pleasures they yield. He takes a granular view of things, focusing on the aspects of landscapes that are easily overlooked. Even things that most might casually tread underfoot—a truculent patch of weeds or dense foliage—are interesting to Guerrier, who pores over his surroundings with careful attention and alacrity. At the time of our first walk last summer, he had recently sold his car and remarked that his new daily commute, consisting of walks and rides on public transport, offered “the opportunity to observe little things.” Over the course of two walks we took late last year near his studio housed in Miami’s Bakehouse Art Complex, he discerned the difference that the time of day induces in the city’s character, registered a host of flowering trees—almond and mango and tamarind, among others—and described the architectural styles of the facades of various homes, dating them to their approximate eras.

His figure, tall and lithe, struck a note of calm within the landscape. He was wearing a bright blue t-shirt that evoked summer and a pair of gray-white trousers that fell loosely about him. His deep brown face emitted an avuncular warmth, one that matched the afternoon’s own. Here was a man who absorbed the tenor of his city and fashioned from it a propulsive energy.

Guerrier’s stride is noticeably unhurried, graceful. His pace has none of the inelegance of the overly industrious walker, no movements strung to the stifling notion of productivity. He moves with even-keeled steps that convey an openness to things yet to be explored, the better to drink in the rhythms, textures, and sights of Miami and its environs, a place altogether remarkable for its geographic and cultural specificity. Guerrier moved to Miami from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as a boy in the late 1980s. He was twelve, and many members of his extended family had already settled in the city. As Guerrier once said to me, Miami is a place replete with potential pictures, composed of endless exposures—an abundance that informs much of his work.

We passed through rows of the winsome, modest single-story homes that line the streets, vivid in their mamey pinks, robin’s egg blues, and other confectionery colors that comprise the city’s unmistakable palette. Lately Guerrier has been fascinated with the creation of what he calls “immigrant space” within Miami’s neighborhoods, and he is developing a film project centered on this phenomenon. For instance, much has been made of the way that people of the African diaspora adorn and furnish domestic spaces, but relatively less of how we fashion exterior space, which Guerrier believes is an equally viable realm for families to “insist on” their presence and sensibilities. He has referred to this as a kind of “projected poetics,” a way to telegraph some measure of their desires and their ambitions. According to this speculation, the exteriors of immigrant homes take on a particular cast, with distinctive ornamentation and the preponderance of certain plants (sugarcane, St. Augustine grass, flowering shrubs) cultivated in stretches of yard that tell of life on a Caribbean island, of a long-ago departure that has settled into something like an arrival.

The Guerrier dérive proceeds at an easygoing clip. He roves purposefully for a few blocks in a single direction before abruptly pivoting to venture in another. He swivels his head, his eyes rivet on something, he sidles up for closer inspection, he crouches. He takes the occasional pause to orient himself, to check the direction of the wind. And then there’s the sudden, almost absolute recognition that a given sight will yield a fruitful image. He takes a photo. He starts again. It’s a kind of choreography that cannot be rehearsed.

For all its idiosyncrasies, Guerrier’s walking is not without antecedents. With his activity, he files into a long, vagrant procession of walkers that stretches back to the nineteenth century, each ambling along through their respective milieux. The familiar figures pressed amid the throng: Baudelaire, the unnamed narrator of Poe’s “Man of the Crowd,” Walter Benjamin. Historically, urban walking has been alternately rendered as the lively, curious stroll, deadening traipse through the capital-blighted metropolis, or the nimble, brisk excursion into city streets; a means to elude the stultifying effects of modern life in the vein of the Situationists. Guerrier has engaged each of these traditions throughout his career. My first encounter with Guerrier’s work was fortuitous. I was an undergraduate enrolled in a course called “Psychogeography’s Prehistory.” Throughout the semester we rooted around for strains of psychogeographic thought in the work of artists and writers who lived in the decades before the term was coined by the theorist Guy Debord in the late twentieth century. But no Black subjects were presented in this history; our investigations skirted the complications of race. One afternoon in the library, while I leafed through the catalog of Freestyle, an exhibition mounted at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001, an image bolted from the page. Its caption read: Flâneur (nyc/miami), 1999-2001. There he was, a flâneur—a Black flâneur. Guerrier invites us to consider the contours of Black flânerie, its stakes and complexities, pleasures and constraints. As the essayist Garnette Cadogan has observed, “Walking while Black restricts the experience of walking, renders inaccessible the classic Romantic experience of walking alone.”

Guerrier invites us to consider the contours of Black flânerie, its stakes and complexities, pleasures and constraints.

The flâneur series is perhaps Guerrier’s best-known body of work. In it, the artist wanders through a dozen urban landscapes in New York City and Miami, his back turned to us. He is dwarfed by gleaming skyscrapers that stretch to precipitous heights, set in stark relief as he approaches the lurid glare of a bodega; his silhouette drifts against the crepuscular glow of a Miami sky. In recent years, Guerrier’s own body has mostly vacated the frame of his pictures. For about a decade, he has regularly produced a series of lush, close-up color photographs of vegetation. “The focus on botanicals and flowers,” Guerrier told me, “became for me at one point a nice shortcut to talk about landscape.” These photographs bear a startling resemblance to William Eggleston’s Jamaica Botanical Series, a little-known body of early work taken in Jamaica in the late 1970s. Like Eggleston, Guerrier is less interested in abiding by conventional frames of reference for composing landscape scenes than in seizing on moments, often angular and oblique, that offer unique ways of seeing and apprehending the landscape. It’s their obliqueness that unsettles our sense of place: How to distinguish these photographs from those taken in, say, Ìbàdàn or Houston? The images look as if they were sliced from a larger, more expansive tapestry. They nudge at the four edges that define them, gesturing to a world beyond the frame.

courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo.

On our second walk, in late October, we headed west along Thirty-second Street, into the neighborhood traversed by I-95, which cleaves Allapattah from Wynwood. In the weeks since our first meeting, Guerrier had opened a pair of group exhibitions he’d organized that featured works by artists working primarily in Miami: the first, Notices in a Mutable Terrain, at Pablo Atchugarry Gallery; the second, between the legible and the opaque: approaches to an ideal in place, at Bakehouse. Guerrier had been turning over ideas for these shows in his mind for some time. “These are two shows that reveal themselves as being an extended essay that I’ve already had notes for,” he said. As with other projects conceived by Guerrier, poetry provides a generative understructure. (He cited the poet Legna Rodríguez Iglesias as an influence). He does not consider himself a curator, nor does he overstate the need for expertise in the curatorial enterprise. Rather he relied on the relationships and experiences—the “texts that he consulted”—with other artists as he readied the exhibitions. The results were bracing: two varied, compelling shows in a city whose art scene and infrastructure is growing but remains fledgling. “There’s a great desire among artists in this scene for such exhibitions,” he told me. “They are not happening as much as they should.”

Guerrier took less photos on this walk. We were largely preoccupied with our winding conversation and looking. The afternoon was blanketed by the raucous barking of numerous guard dogs. There were more houses, beautifully and eccentrically painted. There was a discarded bucket in which dried paint, glowing with an artificial pistachio hue, was suspended like stalagmites. There was the drone of cars and construction, occasionally muffling our voices.

Guerrier’s method fittingly finds an analogue in poetry. He leads his walks with an air of deliberate suppleness, open to the inevitable drifts and detours that constitute a walk. In poetry, the volta marks a shift in tone, signals a digression. Abrupt and swift, it ushers the reader down some unexpected path. Guerrier, of course, is acutely sensitive to the ways that walking affords opportunities to engage the poetry of everyday life; he’s never obdurate. Rather, like the volta, he swerves, rounds a corner, and is met with fresh possibilities.

July 2019. A low, rusting chain-link fence, beyond which stands a pair of rain-slicked, mismatched foldable chairs in a neatly trimmed yard. The fresh rain had pooled in the seat of one, reflecting the wide palm frond that hovered above it. “I don’t see a giant pool, I don’t see a bar pit here. I see a table and chairs,” Guerrier said. “This signals sitting down, talking, and just listening to air passing through. It’s just enough to say, ‘“I live here, and I use my space and, yes, you can see me, but it’s not about you.’”

July 2019. A rain-swept dirt yard strewn with tiny multicolored toys, the kind belonging to dolls and dollhouses.

July 2019. A tall mango tree stands within a wide lot. Telephone wires lay aslant the scene.

“When I was a kid this right here was heaven. A big lot, open, no fence—”

“Soccer,” I cut in.

“Well, soccer is one thing, though we would play American football on the street…”

“It has a mango tree,” he continued. “Every kid in the neighborhood would be eyeing this tree.”

July 2019.

October 2019. Two patterned dresses out to dry hang from a wrought iron covering, swaying in the breeze, possessing a quality one finds in the photographs of Manuel Álvarez Bravo.

October 2019. Baked goods arrayed around the base of a palm tree, an offering. The copper pennies glisten as they catch the light. There were other such offerings left at trees found along the same street. A scene deeply Miami in character, a startling reminder of the many Afro-diasporic religions practiced here.

October 2019. A shrub springs from a scant patch of ground, propped against a two-tone building. It looks as though it has burst open the iron gate that abuts it, hanging ajar.

October 2019.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on States of Leisure.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2020 here.