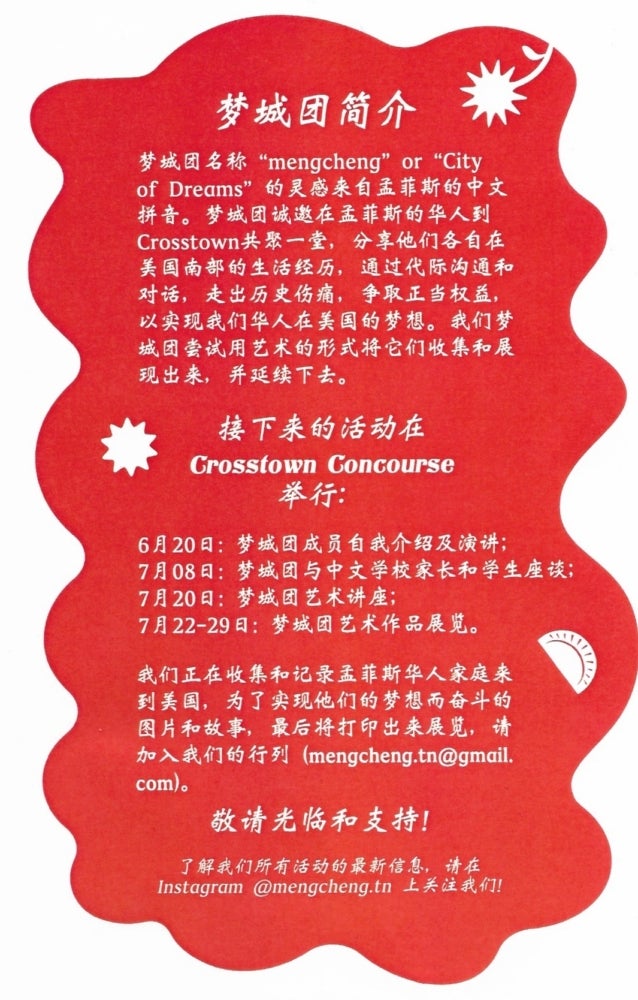

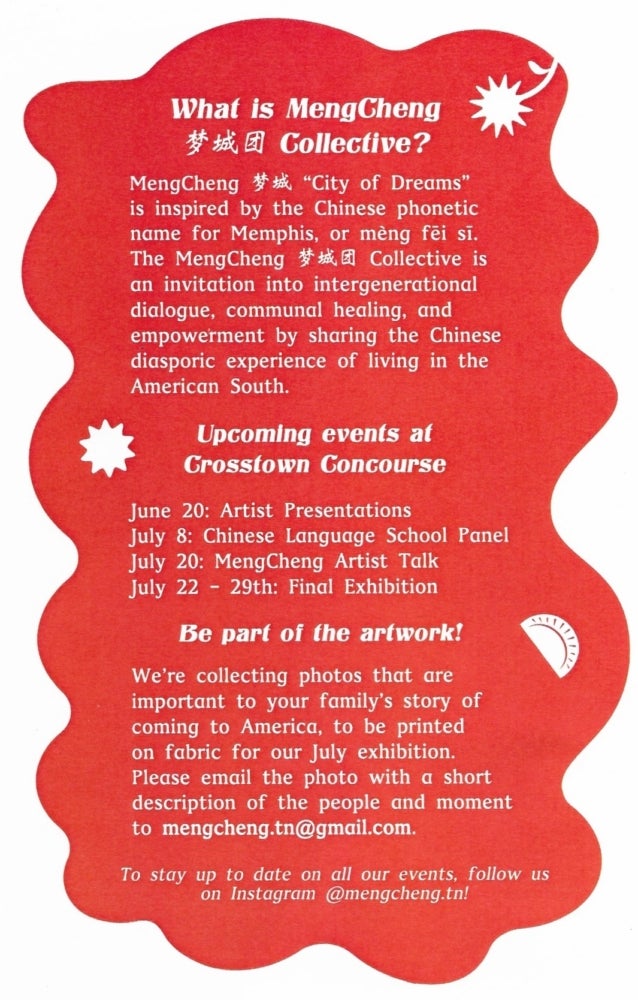

Perhaps it was kismet that Yidan Zeng, Neena Wang, Thandi Cai, and Lili Nacht gathered for Crosstown Arts’ Artist Residency this summer. They worked during Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage month during the 150th year since the first Chinese immigrants arrived in Memphis, TN.1 The four artists live in different cities now, but they grew up in Memphis together. They formed MengCheng Collective 梦城团 last year after communally recognizing their various “unresolved feelings” about having grown up creative, Asian, and American in the American South. Their goal: “Challenge the way our cultural histories have been gathered, disseminated, or made invisible”.2

2022’s documenta fifteen in Kassel, Germany, provided inspiration for how to achieve this goal. Documenta fifteen broke a pattern when it was not curated by a Western art world big shot, but by the Indonesian artist collective ruangrupa, which invited artist collectives rather than individuals to show work.3 ruangrupa organized the fair around the ‘lumbung,’ or Indonesian communal rice barn where families store excess rice and others can take rice they need.4 “[Documenta fifteen] was very much about the process of each collective. You could tell that each collective had spent a year just thinking about a lot of questions and talking and coming up with new ways to be in community and make work together,” Wang said.

MengCheng organized their collective’s social practice and final exhibition, Kai Pa Ti, around potlucks, like the ones they attended at each other’s homes as kids in Memphis. In Cai’s studio they created a “living room” that included archival photos of a century of Memphian Chinese Americans in homely, mismatched frames with dried flowers tucked here and there between the portraits. bell hooks describes a similar wall in her Kentucky home in Art on My Mind. She explains that these images “connect [Black Americans] to a recuperative, redemptive memory that enables us to construct radical identities, images of ourselves that transcend the limits of the colonizing eye.”5 MengCheng seeks a recuperation too for their friends and family in Memphis, “The MengCheng 梦城团 Collective is an invitation into an intergenerational dialogue, communal healing, and empowerment by sharing the Chinese diasporic experience of living in the American South.”6 Comfortable chairs invited guests to that dialogue, as did the opportunity to peruse Zeng’s and Cai’s risoprints and Cai’s literary project about a time-traveling Mississippi carp.

The collective transformed Wang’s studio into a modern “dining room” with an urban edge. Central was a cloud chandelier with metal raindrops and clouds on delicate chains hung behind a handmade “cloud table” that Wang and Nacht built and edged in sky blue. Wang adorned it with earthy ceramic dishes coated in blue glaze. Clouds are a repeated motif that relates to their name (“City of Dreams Collective”, 梦城团). Nacht’s spare painting ALL OR NOTHING (2023) and her gestural pencil drawing freefall (2023) finished the room’s elegance. Instead of a “buffet” in their dining room, the Collective constructed an altar. It held incense, flowers, photos of early Memphian Chinese forebears, and Asian American artists and activists. Meditation sessions brought these community leaders and role models into the conversations MengCheng shared with their community.

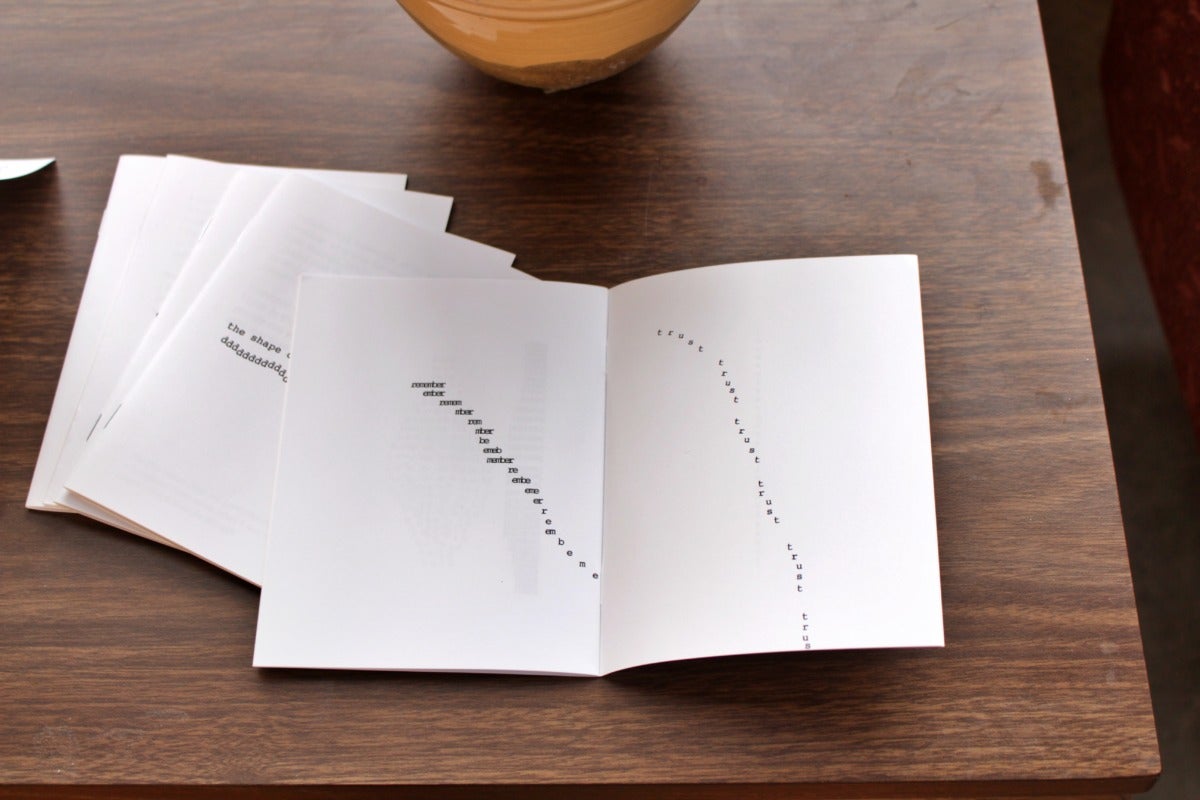

Lastly, the kitchen: Zeng’s poignant Spatial Poetry (series) (2023) carried the weight of these histories into the “kitchen” MengCheng made in Nacht and Zeng’s shared studio. In one poem pouring out grief called Sorrow (2023), Zeng explored gradients in typewritten letters on paper that stacked until they spilled over their edges and dissipated as the emotion paused. Nacht displayed another painting, postcard for memory (2023), that also collapsed present and past in an alternating gradient.

The last piece, 梦飞 Dreamflying (2023), displayed in the kitchen brought the summer’s interventions full circle. Nacht and Zeng gathered the Collective’s families’ portraits and developed them on community-donated fabrics brushed with cyanotype developing fluid. The result was a family reunion in blue and white fabric patchwork. It is reminiscent of thin white clouds strewn across a big, blue, Memphis sky, clouds that decorate the “City of Dreams” Collective.

Their first potluck was open to the public and introduced Crosstown Arts’ attendees to the Chinese American community that enthusiastically shared food. The four artists then curated subsequent potlucks for specific growth and healing within their own circle. A potluck to speak with Asian American creatives in town was especially important because each artist felt they left Memphis after high school because of a lack of opportunity to investigate being Asian, American and creative in town. Zeng explained that the separate, small potluck gatherings were crucial, saying, “We needed to make space that has never existed before. We have to cultivate trust so that we can figure out what those relationships even are.”

Not all the conversations were easy, though MengCheng structured them carefully in order to ease difficult subjects. The artists asked family and community to discuss the challenges of the South and living in the Chinese diaspora by sharing beloved objects at one particular potluck. Each person talked about the physical characteristics of the object and the sentiment, history, and associations their treasures carried. “We wanted our parents to see themselves as artists…[to recognize] their creativity and ingenuity in coming to a new country. That’s why all our potlucks stem from things they’ve done” Zeng said. MengCheng’s inclination to social practice reflects the social practices their parents brought and adapted in Memphis for their kids. “[Kai Pa Ti] is something our parents would have said, meaning to throw a party or potluck. 开 Kai means ‘open, start’ and ‘Pa Ti’ is our way of saying ‘party’”, Zeng said.

MengCheng uses personal history to unravel and then reshape the narrative that Asian presence in the South is recent. Chinese farmers first came to Southern states just after the Civil War.7 Some Chinese immigrants who first settled in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana to sharecrop soon established grocery stores that provided crucial credit for foodstuffs to Black sharecroppers that no White grocers would loan.8 And, after only one generation of living in Memphis, Chinese American Memphians had established the state’s first Mutual Aid Association, the Lung Kong Tin Yee Association.9 These are the kind of cultural exchanges MengCheng and researchers here are re-centering around the South’s dining room table.

MengCheng found their elders were quick to contribute their networks and resources (especially, but not exclusively, food) to their work in the residency—from Viet Hua Grocery Store, Dim Sum King Restaurant, and the Chinese Language School. The effort was mutual. The four artists held a potluck specifically to give of what they’ve gained elsewhere; they spoke with young Chinese Language School students and their parents by detailing their paths after high school and assuaging fears about pursuing creative careers.

MengCheng Collective’s final potluck-exhibition fed each of their goals for their community, for Memphis, and for themselves as artists. They’re proud that they encouraged each other to rest while working long hours in their studios. They are proud of what they taught Memphians about Asian Americans who tilled this land before they grew up here. And they should be proud of the social practice of “intergenerational dialogue, communal healing, and empowerment” that has illuminated the ties that connect them to their community. Memphis has matured in some ways as a creative ecosystem in the past decade to allow for their work here. Instagram posts since leaving Memphis this summer wax proud, nostalgic, and filled with longing. They’re hungry for more Southern potluck.

[1] Joyska Nunez-Media, “The Story of Chinese Laborers and the Reconstruction South,” blog, May 2, 2022.

[2] MengCheng Bilingual Flyer, “What Is MengCheng Collective?,” 2023.

[3] ruangrupa is intentionally lowercase. “ruangrupa — Ruru,” ruangrupa, January 4, 2023, https://ruangrupa.id/en/.

[4] “Lumbung padi,” in Wikipedia bahasa Indonesia, ensiklopedia bebas, February 28, 2023.

[5] bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press, 1995), 54–64.

[6] MengCheng Collective informational flyer, Crosstown Arts, Memphis, TN, 2023.

[7] Joyska Nunez-Media, “The Story of Chinese Laborers and the Reconstruction South,” blog, The Story of Chinese Laborers and the Reconstruction South, May 2, 2022.

[8] Far East Deep South (New Day Films, 2020).

[9] Joyska Nunez-Media, “The Story of Chinese Laborers”.