Along the swift rivers of Appalachia, Daniel Essig collects the ephemera that will become his work—fossils, bones, fragments of mica that catch the light. Working from his Asheville studio, he transforms these found materials into sculptural books that bridge the boundaries between ancient spiritual traditions and contemporary craft, creating what he calls “containers for the sacred remains of the past.”[1]

Consider N’kisi Bricolage Trilobite (2007). It is an apt name, as bricolage describes a collage of ideas, this sculptural work serves as a hybrid of the carved figure and artist book. Crafted from painted mahogany and rusty found metal, the figure resembles an abstracted mask. Three smaller masks halo the crown of the head, shrouded by a sea of scraggly and spiky nails for hair. These nails produce a different visual effect as one’s gaze travels just below. The nail heads, hammered deep so only their surfaces show, create the illusion of perhaps fifty watchful eyes—a protective gaze that seems to guard the trilobite fossil consecrated in a niche at the figure’s third eye. According to this ritual, each nail represents a time that the figure’s power was invoked.

To form the nose, eight miniature books are housed in slots, falling towards a chin whose facial hair is also made of tiny books and scrolls dangling from chains. These books, made from both 1800s text and by hand, emanate a powerful aura due to its coupling with such strong and arresting symbolic associations. As these traces of the past come into confluence, the viewer is keyed into the emblematic power of knowledge and ritual. Working in Asheville—a city where African American, Cherokee, and European traditions have long intersected—Essig’s N’kisi figures speak to the region’s complex spiritual heritage. Just as Appalachian ‘granny witches’ created protective charms using local materials and spiritual practice, Essig’s figures function as contemporary guardians, housing sacred remains within forms that bridge African protective traditions, Indigenous porto-writing, and the sacred essence of the natural world.

Essig’s path to this synthesis began during photography studies at Southern Illinois University, where he joined professor Chuck Swedlund on caving expeditions throughout the Southeast. In those subterranean depths, he developed his collector’s eye, gathering specimens by both hand and lens. Among salamanders, insects, and small fish, he discovered what he calls “the beauty of decay” and declared these underground spaces sacred. He chose to frame his photographs in books, rather than upon the wall, to compel the viewer into active contemplation and exploration, engaging the sensorial body the same way he did over and under these hallowed grounds.

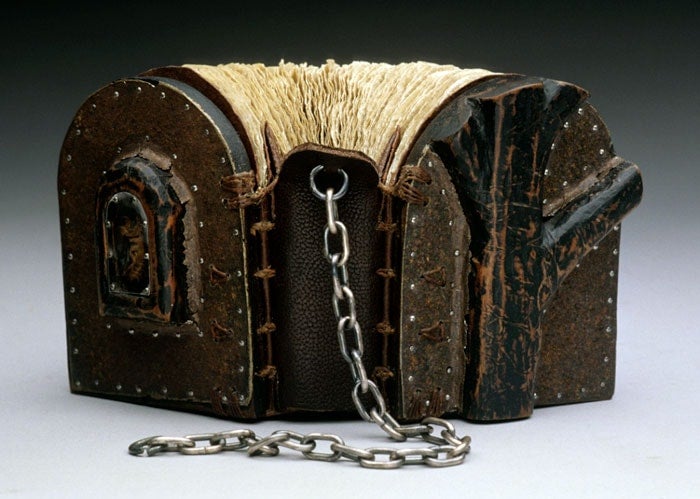

This tactile imperative drives his work. In Metamorphosis (n.d.), crafted from mahogany, tin, and leather into a fanned, arching corridor measuring just 4 x 6 x 3 inches, viewers must cradle the work in their palms, smell the age of handmade paper, and hear the silver chain clanging as it dangles from the spine. Within the cover lies a dead cicada—collected from his trawling expeditions—enshrined forever as a symbol of transformation, its characteristic buzz now only memory.

The cicadas song spans throughout the Southeast and just beyond—-an emblematic hymn. Essig pulls the molted cicada shells from tree trunks and describes their life cycles in an essay for The Penland Book of Handmade Books (2004): beginning as nymphs, cicadas “live underground around a tree for years, then tunnel out and crawl into the tree, where they molt.”[2] Just as their life cycle revolves around trees, so does his practice—crafting books from wood and paper while housing their molted inhabitants within. This creates what scholar Anne Burkhart calls “a vision of books as laboratories for the invention and performance of perceptual systems: new worlds carved out of the wilderness of human thought and language.” In collecting this ‘wildnerness’ and placing it within the gilded cage of intellectual human design—that is, the book—Essig enshrines traces of existence (whether they be animal or plant) into a larger cultural consciousness of meaning.

Much like how the books operate as tombs for the singing bugs, Essig likes to think of his book-sculptures as reliquaries for both the nonhuman and the human, typically of ancient aesthetic. During his cave expeditions and subsequent adventures through the prehistoric Appalachian mountains, Essig found himself drawn to indigenous petroglyphs—rock carvings that served ritual and symbolic communication purposes. These “proto-writing” systems communicated knowledge through visible marks rather than words. Essig, who never writes in his books, similarly opts for meaning through format and materials. His work acknowledges that certain stretches of land remain “permeated by meanings”[3] that contemporary viewers can sense but not fully access.

Essig literally bridges this conceptual gap in his Bridges series. By constructing two oversized bookends with smaller leaves sewn between, and turning the final binding onto its side, the pages hang in a delicate balance, waving in the air like prayer flags or protective charms suspended between worlds. In Crinoid (1997), the bookends loom like plinths at 22 inches tall, with handmade kobo and iris paper sagging heavily in-between—the weight of accumulated knowledge and memory made visible. The exposed binding recalls old and weathered footbridges that hang precariously between cliff edges, but also the umbilical connections between past and present, between the sacred remains housed within his reliquaries and the living world that continues to venerate them. Here, the sewn ‘centipede’ binding crawls over the edifices like roots or veins, suggesting that these containers for the sacred operate as conduits of fossilized wisdom into contemporary consciousness. Essig says, “Sometimes friends collect objects as souvenirs for themselves, then turn them over to me when they want to forget those particular times.”[4] Essig’s art books, thus, ensure that the wisdom embedded in Appalachian stone and bone continues to watch over and guide those who encounter his sculptural prayers.

Much like how the books operate as tombs for the singing bugs, Essig likes to think of his book-sculptures as reliquaries for both the nonhuman and the human, typically of ancient aesthetic.

Ultimately, Essig’s sculptural books become libraries of the spirit, where each housed specimen serves as both relic and revelation, reminding us that the sacred has always been present in the ephemeral world around us. Through his sculptural books, he offers a model for contemporary meaning-making that honors both the scientific and the sacred. He preserves, protects, and presents the talismanic power of this region’s natural world for those who have forgotten how to see it—whether it be Cherokee petroglyphs on forgotten rock faces or African spiritual practices carried in memory. In this way, his sculptural books become illuminated expressions of Appalachian resilience: beautiful, functional, sacred objects that prove survival itself can be an art form.

[1] Daniel Essig, “Traces of the Past, Visions of the Future,” in The Penland Book of Handmade Books: Master Classes in Bookbinding Techniques (New York: Lark Books, 2004), p. 13.

[2] Daniel Essig, “Traces of the Past, Visions of the Future,” in The Penland Book of Handmade Books: Master Classes in Bookbinding Techniques (New York: Lark Books, 2004), p. 13.

[3] Christer Lindberg, “Magical Art — Art as Magic,” Anthropos 111, no. 2 (2016), p. 606.

[4] Evan Davison, “Daniel Essig: A Visual Diary,” YouTube, December 31, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWa8Qhj93Ao&t=9s.