Earlier this week, the Pérez Art Museum Miami announced it had received a one million dollar grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation supporting the museum’s new Caribbean Cultural Institute, which will develop exhibitions, publications, and programs focused on the Caribbean and its diaspora. PAMM director Franklin Sirmans said, “Miami exists as a northern border of the Caribbean and contains elements of the Caribbean in its peoples and culture that make it a nexus point for the study of the region. It is integral to our mission to further cultural dialogue within that space, and to amplify it outwards to the international community.”

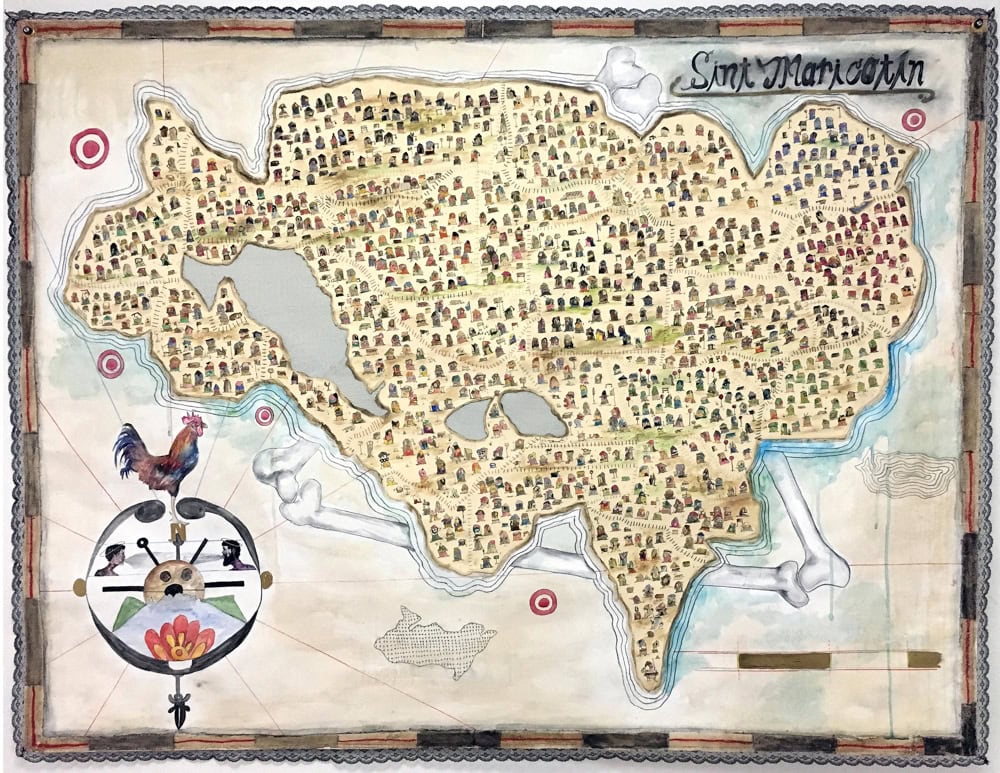

The announcement came mere days ahead of the opening of The Other Side of Now: Foresight in Contemporary Caribbean Art at PAMM, a survey of art from the region curated by associate curator María Elena Ortiz and Dr. Marsha Pearce, a cultural studies scholar based at the University of the West Indies St. Augustine campus. The exhibition advances an alternative to viewing the Caribbean and its cultural production according to narratives of catastrophe—which “frame the region in terms of then and now,” according to the curators—and instead imagines possibilities for personal expression, resourcefulness, and survival in the not-so-distant future of the region.

I spoke with curator María Elena Ortiz about organizing The Other Side of Now a few days before its opening in Miami on Thursday, July 18. Our conversation was conducted over the phone in July 2019 and has been edited for publication.

Logan Lockner: In the press release and the language around the exhibition, there’s this question: What might a Caribbean future look like? This exhibition posits the Caribbean not only as a geographic location but also as a temporal space, and I was wondering if you could speak about how you came to frame it in that way.

María Elena Ortiz: This exhibition started as a conversation between Marsha Pearce and I—we met back in 2014 in Trinidad when I was the winner of the CPPC [Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros] Travel Award for Central America and the Caribbean. Through that meeting and many other meetings, we began discussing how we could think about contemporary art from the region that wasn’t solely focused on the past, or that dealt solely with ideas of trauma and catastrophe. At the beginning of the conversation, there was a lot of interest in Afrofuturism and how that might appear or operate differently in the US and the Caribbean. But then the 2017 hurricane season happened. Even before then, I had questions about how much agency we could have in the present now, and how we might think of the future as tomorrow, not this far-fetched Jetsons reality. Rather, how can I have more autonomy in my life? Those were the conversations that were driving the spirit of the show, so we decided to translate that into the exhibition itself by asking those same questions to artists. Many of the artists created new work for the exhibition, and other artists are showing work that they felt and we felt was in tune with the topic at hand.

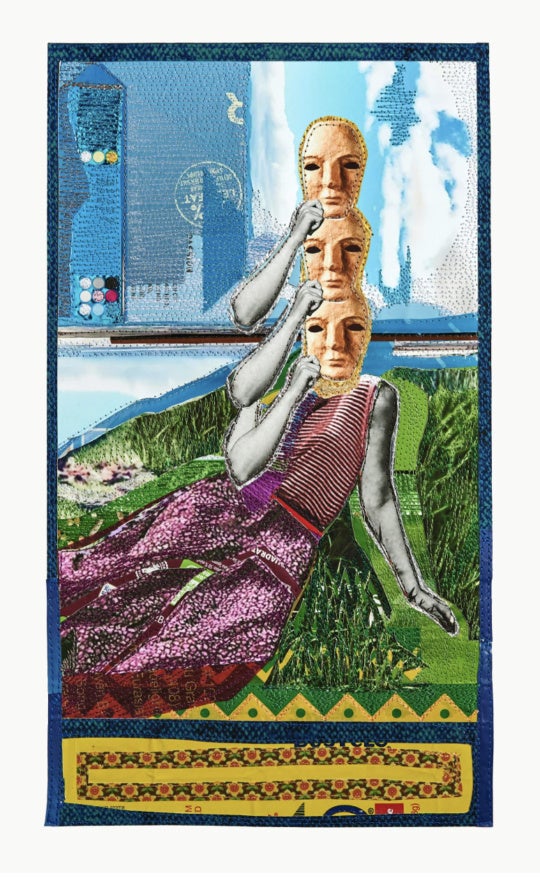

There are artists in the exhibition who are living in the Caribbean and others who are part of the diaspora. It was important to think about the region as a post-national space and the ways in which people in the diaspora around the world are influencing the discourse of contemporary Caribbean art together, so that’s what you see in the show. Aside from the temporal question, it’s also about promoting different images of ourselves.

LL: Given the city’s proximity to the Caribbean and its connections to histories of the Caribbean diaspora, what does it mean from an institutional perspective to present this kind of exhibition in Miami? You’ve spoken before about the work PAMM does as “telling a history of Miami.” How does this exhibition play into that?

MEO: It’s a contested statement, but we consider Miami part of the Caribbean—not just part of the history and geography of the American South but also part of the Caribbean and, by extension, Latin America. It’s not only an issue of physical proximity but also cultural presence. Since the early twentieth century, Miami has been a home to people from the Bahamas and Jamaica, and then, of course, Cubans, Haitians, Puerto Ricans—people from a lot of different communities built this city. The other day, I was walking around and saw a fruit that is native to Jamaica, so obviously someone brought that over. It’s not just people but also fauna and vegetation. We’re here to be cognizant of the communities we serve. People want to see themselves in the museum. It’s geography but also who our community is.

LL: You mentioned that many of the participating artists created new work for the exhibition. How did they respond to the question What might a Caribbean future look like?

MEO: The works are very different, but when I was writing my essay for the book, I found a common connection in this idea of personal autonomy and how, perhaps, through personal experience we can have some kind of determination or empowerment in a particular situation.

For example, the artist Cristina Tufiño made a video and a sculpture inspired by her father and his own hero’s journey. He had a very well-known, iconic restaurant in Puerto Rico. In the 90s, he decided to leave the island and leave the restaurant to their friends. He realized he couldn’t take his work with him, so he left those resources for the people who continued living there. The restaurant is still open today and very well recognized. It’s a very personal experience, deciding when to go and when to stay.

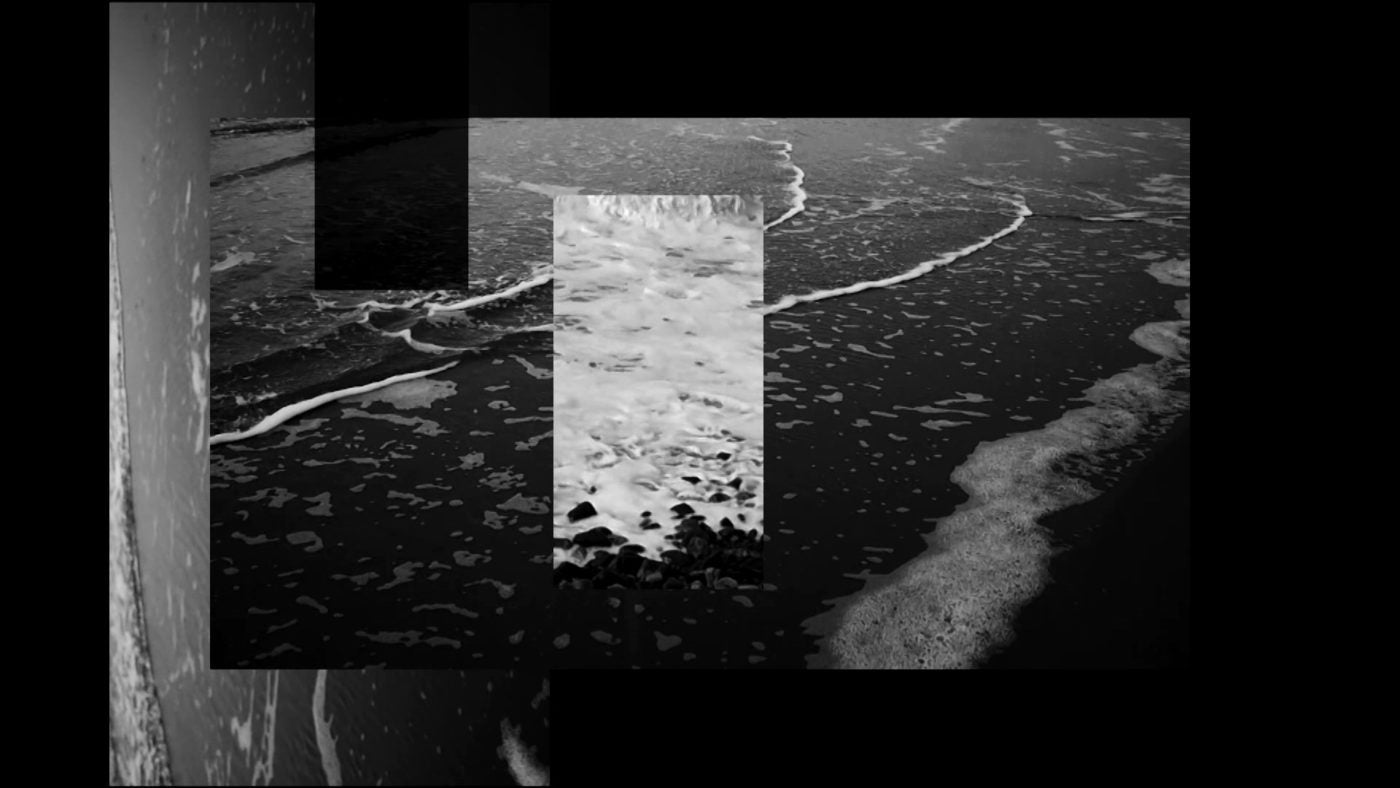

There’s another work by Deborah Jack—another video—where she composes abstract imagery based on the coast of Saint Martin—where she’s from—and geometric forms, again, pushing against stereotypes of the Caribbean, and the video is overlaid with a hymn she used to sing as a child, going back to the personal.

LL: This project also involves a publication. Does that take the form of a standard exhibition catalogue, or did you take a different approach?

MEO: It is a museum catalogue, but I was really interested in this idea of different sources of knowledge. Humans have different ways of creating knowledge and experiences, so for that reason we included not only curatorial essays but also an essay by an economist, an essay by a film scholar, and a poem by Aja Monet and two fiction stories, one by Cuban writer named YOSS and another by a Dominican writer named Rita Indiana. Different people have different ways of approaching these questions that can be equally important and significant.

The Other Side of Now: Foresight in Contemporary Caribbean Art is on view at Pérez Art Museum Miami through June 7, 2020.