It can take up to five hours—a journey over land and across Amazonian waterways—to reach the outskirts of Pikin Slee, a Maroon village in Suriname. Famously difficult to penetrate, Maroon habitations exist on the margins of one world and the center of another. This inaccessibility has always been by design and for survival. For Cornelius Tulloch, this journey into the rainforest began a three-day communion with the Saramaka, one of six remaining Surinamese Maroon tribes. There in residence with the support of Diaspora Vibe Cultural Arts Incubator (DVCAI), the Miami-based artist of Jamaican descent found within his practice a deep capacity for holding the unknown, a renewed sense of borders and boundaries, and a strong case for keeping secrets.

There has been a long and insistent tension between what is hidden and what is revealed throughout Tulloch’s work. I first met the artist across this breach through a series of deeply saturated photographs, and again as he continued to develop his dark, lush portraiture work. For all the potency of Tulloch’s images, there has always been a sense of controlled impenetrability. Disembodied limbs thrust boldly into frame; a copious bounty of tropical flora; the artist himself aching upwards out of a grain mass as in The Harvest (2018).

The conspiratorial generosity toward nature also defines Tulloch’s practice: a space where flora, fauna, and figures intermix, mingle, and merge. Graduating from Cornell University with an architecture degree in 2021, Tulloch consistently employs this training in conversation with the world around him. In his immersive 2022 Faena Art Project Room installation, Bougainvillea: An Exploration of Adornment, the entirety of the space took on the hues of the thorny, ubiquitous plant. The overall effect was both alien and familiar, armored and exploratory, a dancehall dreamscape behind a magenta velvet rope.

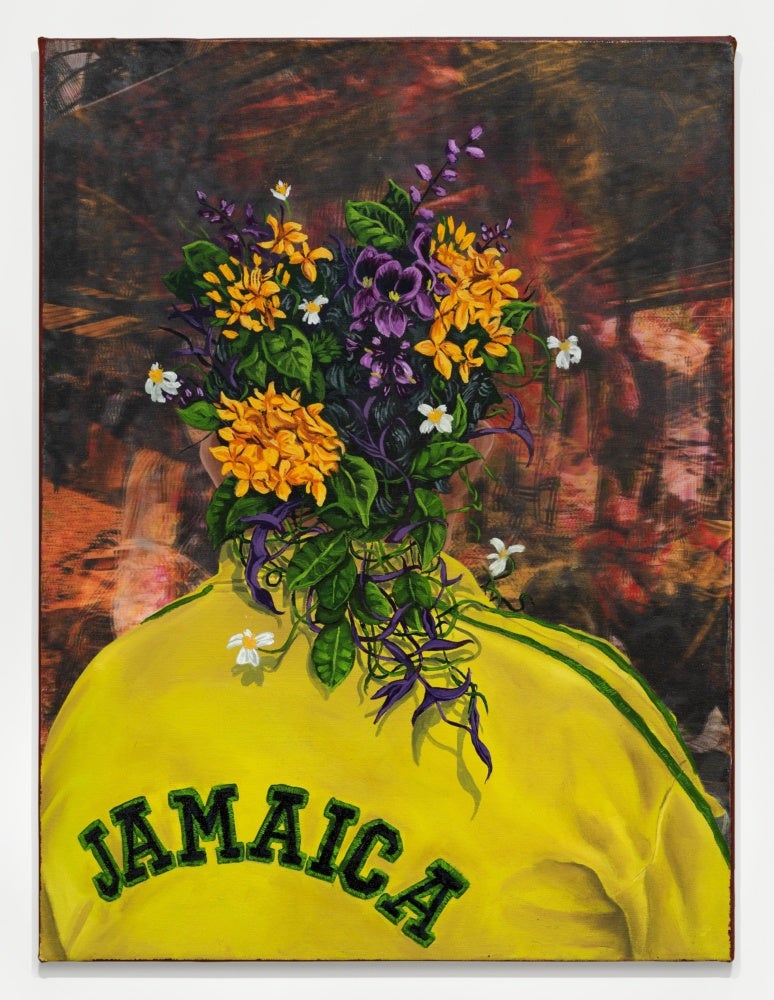

Throughout Angisa: a language of living (2024), the collection of work that emerged out of his time in Suriname, tropical plants curl across and around Tulloch’s subjects. The gesture is notably protective and even, at times, subsumes the figures completely, as seen in KURT (2024). Outfitted in a bright yellow jacket, an arc of embroidered lettering spells out “JAMAICA” across the back of a Januslike figure. For the artist, Jamaica serves as a personal touchstone and point of departure towards an expansive body of work. The borderlessness of the Caribbean is one that Tulloch and myself intermittently attempt to decipher, sharing and returning to radar images that render the region as a mountain range, defined only by depth and breath. This reorientation of the Caribbean, from discrete nation states to a continuous landscape, shapes much of Tulloch’s thought process and art-making.

It is also the driving force behind Miami-based DVCAI. For over a decade, the organization has forged deep connections within Suriname’s art community. This work, founder Rosie Gordon-Wallace asserts, is anchored in the desire to become the most strategic and creative network for Caribbean artists throughout the diaspora.1 The Suriname residency represents a vital tie to a region where the Transatlantic link to Africa is activated and alive. Critical components of the residency include time spent meeting local artists, exploring the country with a guide, and experiencing life as lived by the Surinamese. Though DVCAI facilitates highly individualized visits for its participating artists, Gordon recommends they do minimal research in advance, acknowledging that much of the existing information on Suriname is neither sensitive nor careful in regards to illustrating the complexities of the region.2 Trusting the process involves allowing for the productive messiness that comes with the Caribbean.

Of his own curiosity, Tulloch is mindful of the legacy of consumptive and extractive European exploration that defines contemporary tourism culture throughout the Caribbean. Much of this work involves shifting from Western epistemological notions of time, space, and history to reflect a more thoughtful engagement with a continuously evolving Caribbean. While in Suriname, conscious of the weighty process of documentation, Tulloch replaced his large professional camera with a small and less obtrusive model. Photographing only when the time felt right or when a measure of trust was established, Tulloch repositioned himself as a photojournalist rather than an artist. As opposed to producing an anthropological survey of a diverse people and culture, this conscious effort generated an unrestrained visual language that captures the emotional and atmospheric tenor of his residency time.

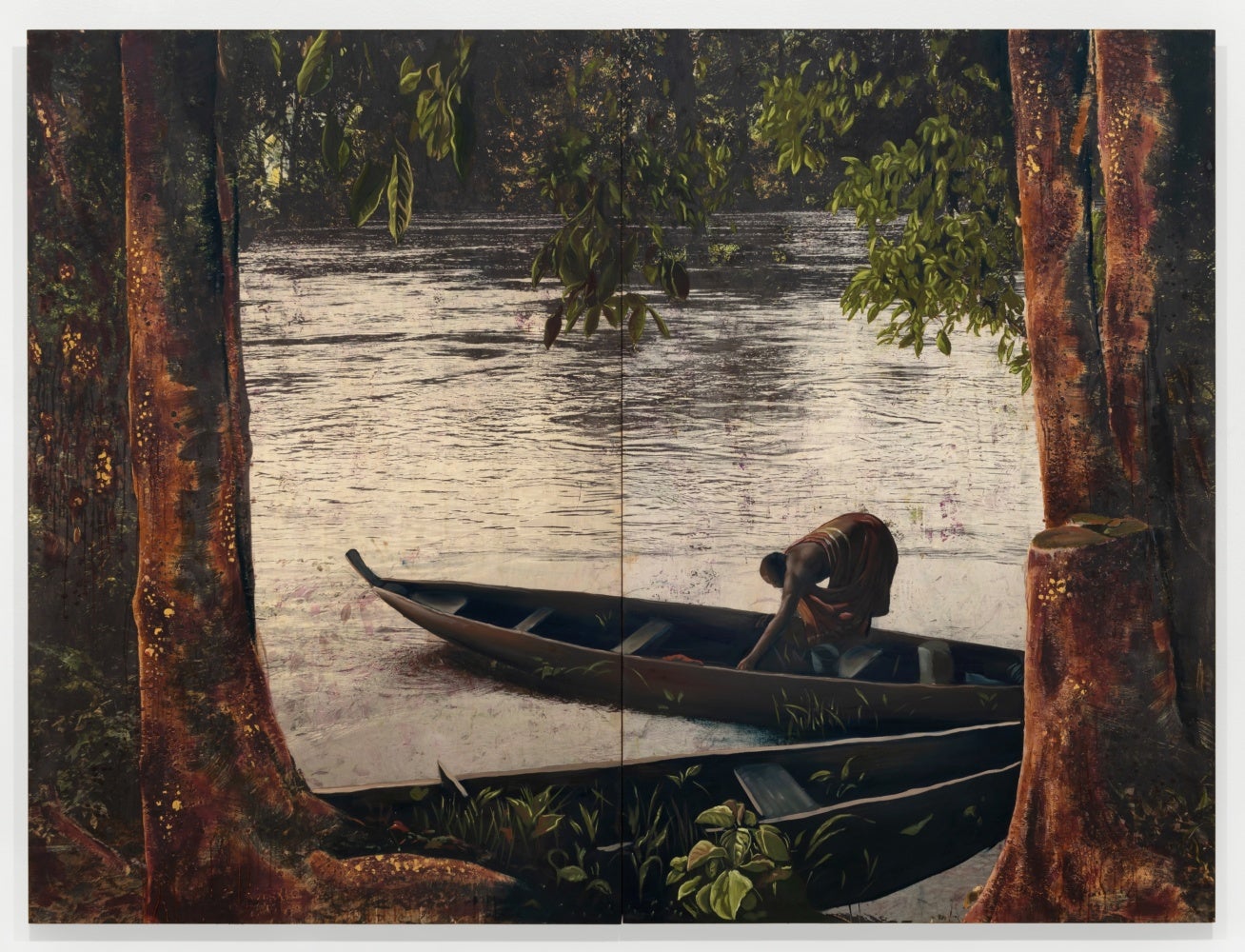

The role of respectful observer is best illustrated in the serene and reflective Raft of Samaaka (2024). At 60 by 80 inches, the diptych features a solitary painted figure stooped over in a canoe, framed and protected by two large trees in the foreground. As viewers, the experience feels completely mediated by Tulloch, who himself reimagines the scene from a position just beyond the shoreline. Despite his presence, the scene remains uninterrupted as the Maroon’s work in the canoe proceeds. Playing with the dimensionality of cold wax on the UV-printed and painted surfaces filled with dense vegetation, it is as if Tulloch takes on the role of bold explorer solely through material use.

It is this aptitude for wielding light and color that simultaneously obfuscates and illuminates that made a deep impression on Miguel ‘EdKe’ Keerveld. Keerveld, a Surinamese artist based in Brazil, spent time with Tulloch during his time in South America. Keerveld became the subject of a work produced out of Tulloch’s time there, which was then exhibited at Andrew Reed Gallery in Miami for the artist’s solo exhibition titled Angisa: a language of living, on view from July 11 to August 16, 2024. Their exchange, Keerveld noted, resonated with alakondre, a uniquely Surinamese concept that represents an all-encompassing nationhood or more broadly, the totality of space and time.3 Difficult to translate completely, alakondre itself exists without borders, even amidst one’s own sense of personal and cultural boundaries.

The conspiratorial generosity toward nature also defines Tulloch’s practice: a space where flora, fauna, and figures intermix, mingle, and merge.

In 1966, American writer Amiri Baraka introduced the idea of “the changing same,” which argues that the rhythmic patterns of African American music are both borrowed and original.4 Theories of continuity-in-change in a Caribbean context continue to be offered by figures such as Puerto Rican author, Mayra Santos-Febres, who suggests that the Caribbean is not a static or homogeneous entity, but a space characterized by diversity, fluidity, and continuous change.5 Tulloch’s emerging visual language summons shared patterns of resistance and evolution across the region. The work resonates with networks of connectivity that transcend both borders and language. What was on view in Angisa: a language of living is a profound reflection of Tulloch’s experiences in Suriname and the diasporic roots he unearthed during his time there; relationships that the artist continues to explore and protect in his current trajectory.

[1] Rosie Gordon Wallace (Founder, DVCAI) in discussion with the author, October 2024.

[2] Rosie Gordon Wallace (Founder, DVCAI) in discussion with the author, October 2024.

[3] Miguel ‘EdKe’ Keerveld (artist) in discussion with the author, October 2024.

[4] Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones). “The Changing Same (R&B and the New Black Music).” Black Music. 180-211.

[5] Mayra Santos-Febres “The Fractal Caribbean, New Literatures of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic” (public lecture, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, September 12, 2019).