You could say Pasadena-based filmmaker Ondi Timoner has a thing for problematic men. The only director to receive the Sundance Grand Jury Prize twice, Timoner has made several films centered on figures she has called “impossible visionaries”—men (as well as a few women) whose creativity often comes with a sidecar of chaos.

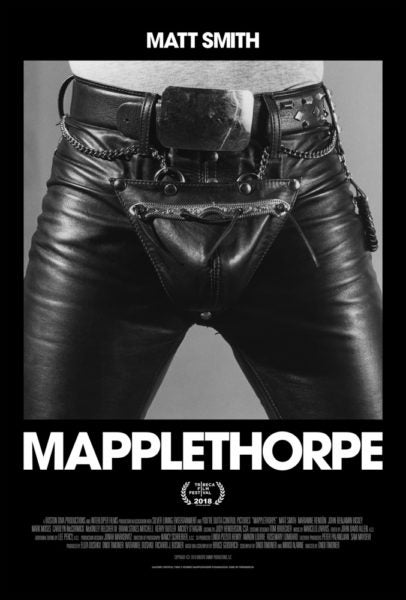

Screening on October 6 as the closing night selection for Atlanta’s LGBTQ film festival Out on Film, Timoner’s first narrative film, Mapplethorpe, focuses on one of the director’s stock-in-trade provocative, often-troubled iconoclasts. Her film chronicles the formative relationship between the eponymous New York photographer and his creative collaborator and lover Patti Smith and follows him through his death from AIDS-related causes in 1989. With a hypnotic central performance by British actor Matt Smith—who captures both the artist’s vulnerability and his cruelty—and an unflinching dedication to showing Mapplethorpe’s controversial, sadomasochism-centric “X Portfolio” onscreen, Mapplethorpe reminds viewers of a not-so-distant time when the culture wars of the late ‘80s and ‘90s put contemporary art’s more conceptual, risk-taking tendencies on the public’s radar, and the collision of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Reagan-era politics, and Mapplethorpe’s photographs created one of the most fascinating, defining moments in recent American cultural life.

In her TED Talk “When Genius and Insanity Hold Hands,” Timoner described the film subjects who have captivated her, including “the Warhol of the Web,” dot-com millionaire Josh Harris. Timoner’s fascinating 2009 documentary We Live in Public (slated for a Ben Stiller-directed adaptation starring Jonah Hill), shows how Harris made and lost his fortune during the formative early days of the internet and predicted its corrosive invasion of private life. Harris also staged a remarkably prescient Y2K art project “Quiet: We Live in Public” in the bowels of Manhattan where 100 participants slept, ate and performed on live webcam. Timoner’s first Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner, the critically acclaimed 2004 film Dig! followed the scorched earth path of seminal indie band the Brian Jonestown Massacre’s heroin-addicted front man Anton Newcombe, and more recently Timoner has turned her camera on British bad boy comedian Russell Brand in Brand: A Second Coming (2015).

A bit of an impossible visionary in her own right, Timoner is a maverick female filmmaker with a bit of a punk rock shamble, tailor-made for the #MeToo era, and she’s made inroads not just into documentary but new storytelling forms as well. Timoner has been releasing content through her online video portal A Total Disruption to tell the stories of artists and entrepreneurs and more recently has been touring the country with her traveling talk show, WeTalk, about the women shaping our culture.

Timoner took a break from shooting her documentary on the opioid crisis to speak with Burnaway contributor Felicia Feaster, detailing her identification with this groundbreaking photographer and sharing the story behind a Mapplethorpe project more than twelve years in the making.

FF: What dimension of Mapplethorpe’s personality or life most interested you and made you want to make a film about him?

OT: He’s someone who took on the impossible and sort of acted impossibly along the way to make us see what society deemed obscene and beautiful. He insisted that we see the life that he’d fallen in love with.

I wanted to bring him alive. I’m usually a documentary filmmaker but I also love scripted films. It’s been twelve years of developing this story but I never wanted to make a documentary about Robert Mapplethorpe. I always wanted to bring him alive and create an anthem for artists, because I felt like it could really influence a generation of young artists, showing them not to take no for an answer and why they should stick to their guns and have the rest of the world see what they see.

FF: Did you feel like you needed to correct something about Mapplethorpe’s legacy?

OT: No, we decided—Matt and I—that we were going to pull no punches and were going to really show when Mapplethorpe isolates, when Mapplethorpe becomes predatorial, when everything needs to be framed up and possessed, when he is knowingly transmitting HIV/AIDS—things like that that are hard for many people to swallow.

I feel like this person had massive flaws; he was in pain, and he inflicted pain. He also created incredible beauty and saw things that we didn’t see quite yet, and he was so tenacious.

I totally related to him because his camera led him into worlds that he otherwise never would have entered. He was so shy and so scared, and he was raised Catholic. Everything he was entering was forbidden—but mediated by the camera, he could do it. And that’s how I started. I started with women in prison when I was a Yale student and that camera became a bridge into worlds I could never otherwise enter. That is one of the things I relate to. I relate to the isolation as well. Even though I’m surrounded by people all the time, it is a very isolating process in so many ways to have to think of how to construct a film, whether it’s a doc or a scripted film. It’s a very solitary experience.

FF: Mapplethorpe’s S&M work still has the power to shock. Do you have a favorite body of work that you really connect to?

OT: It still has [that power]. It’s things like those guys in leather and the chains in that Chesterfield furniture. It’s that contrast. As if they’re saying, “We’re in your living room now. We have means and we’re here to stay.” That was kind of the journey he went on in terms of making S&M visually palatable and turning it into art worthy of Rodin and Michelangelo.

OT: Did you decide to shoot Mapplethorpe in 16 mm and 8 mm because you wanted a contrast with the elegance of his photography?

OT: No. I shot it in 16 mm and Super 8 because I am a real believer in the power of celluloid even though I am a digital kid in that I grew up in that era where I couldn’t have started making anything if it were all film.

I’m a real believer in the texture and the perfectly imperfect cellular makeup of film. I believe in its power to move and emote in a way that clean, clean, clean 4K video doesn’t. Film elevates, and for Mapplethorpe what was important was just to bring the period alive. It was so important that the film be as beautiful as his work, and I really didn’t think we could accomplish that without film. We needed the grain; we needed it to feel like Nan Goldin and all that.

FF: Why did you use archival footage throughout the film, showing the pop culture and political landscape Mapplethorpe worked in?

In my script, I always had different segments that anchored my movie in the decades when it took place because I felt like it was really important for the audience to understand this is recent history. There’s Ronald Reagan denying the existence of the AIDS crisis while thousands and thousands of people needlessly die. It was interesting to me to then zip to the ‘80s with Pac-Man and [John] McEnroe and get people to think, “Oh wow, he’s really existing, this is not a made-up story.”

FF: Although the development is relatively recent, it’s hard to imagine a time when photography wasn’t considered fine art in the same sphere as painting or sculpture. Do you think that prejudice still persists for you as a documentary filmmaker?

OT: It’s really interesting. Sometimes you hear people say, “Is it a movie or is it a documentary?” Or people say, “Is it a drama or a feature?” None of those words make any sense to me. Now even docs have actors in them sometimes and include reenactments and dramatizations. [Docs] are some of the most provocative things on TV. I don’t use those words because all my movies and the movies I appreciate that are documentaries are dramatic, have narratives, and are feature length, or are shorts. But I think overall the general consciousness of society is changing when it comes to this art form; it’s really the golden age of documentary.

I think of when I started out in the early 1990s: I came out of Yale having won the Yale film prize and graduated cum laude, and yet I couldn’t get into film school because I described myself as a documentary filmmaker. I guess it wasn’t important at NYU and UCLA to have me around, so I worked at a public access station and taught myself to edit with my brother. We taught ourselves AVID and came up through the music business making music videos and electronic press kits. We were nominated for a Grammy in 1998, which helped put us on the map, and from there the success of Dig! at Sundance really kicked off my career on a new level when I was 30.

As a member of the Academy [of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences], I get everything that qualifies for competition sent to me, and it is amazing to see the resources that are going into making docs now and how every topic under the sun has some documentary being made about it. It’s a really different time. It’s exciting and really important. It’s a really transformative art form. It’s something that allows people who don’t have a voice to be heard.

Mapplethorpe screens at the Plaza Theatre on Saturday, October 6 at 9 pm as the closing night selection for Out on Film, with an introduction from filmmaker Ondi Timoner.