John J. O’Connor was born in Westfield, Massachusetts, and received his MFA from Pratt in 2000. He currently lives and works in New York, and his current show at Pierogi Gallery in Brooklyn runs through November 10. A catalogue was published in conjunction with the show, with texts by Robert Storr, John Yau, Rick Moody, and Susan Swenson. He has shown extensively in the US and abroad, and his work is included in the collections of the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the New Museum of Contemporary Art. He is currently included in Classless Society at the Tang Museum. We became friends at Skowhegan in the summer of 2000, and he is easily the best Ping-Pong player I have ever faced.

Ridley Howard: When we met over a decade ago, you were making work about chance. It seemed like a way to foil the aesthetic expectations of abstraction … with a nod to Cage and Jensen. Then you started doing work that was more statistics driven, but it was wild and obsessive. The new work appears to be much more about language and subjectivity.

John O’Connor: Yeah, when we were at Skowhegan, I used chance mostly as a way to subvert my habits in making abstraction—it felt like a collaboration with some outside force. That summer I started to think of chance more as a reflection of the way the world actually operated. Cage’s works seemed to fall into two categories for me then—the works like 4’33” were meant to allow us to experience the randomness of life by paying attention, but in other works, Cage actively engaged chance as a method of making things via the I Ching—his prints, etc. I started to focus on chance as a way to deal with both of these ideas simultaneously. I wanted to literally take the processes from the world that I was interested in and use them—not just randomness but others as well. It was my way of trying to maybe make sense of what was happening around us. That summer I started to look for information related to how the world ordered or disordered itself. I’m now thinking of language as the whole evidence of these processes—how the brain thinks, how and why people communicate via the web versus how we speak to each other in person or nonverbally. Things like that.

RH: At what point did artificial intelligence become an interest?

JO’C: Maybe [for] the first time was when I was a kid. I remember that I tried to make a lottery number generator out of my Texas Instruments computer, thinking it could make “special” numbers that could win for my family. We never won. But because I made it, it felt more like person, you know?

As an adult, I saw the Turing test as a way to understand how some fabricated thing could become intelligent—come to life, almost. Those computers were obviously programmed to react and respond to our ways of communicating, which is basically what we do, as humans. That points to our ability or inability to act out [of] our own accord, out of free will.

More recently, I’ve been experimenting with Cleverbot because its way of communicating is derived from actual conversations it’s had with real people. Since it has an accumulated knowledge of the ways we speak, I was thinking of it as a collective human consciousness. Looking into this through the language of the bot seemed a way to dig into the core of what makes an experience real. Recently, with my friend Nat Clark’s help, I’ve been working on my own ‘johnbot’. We’re trying to make it communicate the way I do. I continually add key words to its database and my responses to potential questions. People will ask it about my art, too, so we’re working on a way to move that in interesting directions. I’ve even asked my four-year-old son, Ronan, to help, and we’re now entering some things that I say while I sleep-talk at night. I’m hoping that when someone is talking to it, they might get the feeling that they’re actually talking to me, or someone who acts like me. Or they’re being fooled.

RH: This show really seems to frame something about contemporary experience. Certainly yours, but there is a more universally understood anxiety around Internet realities, hypercapitalism, “authentic” experience, and emotion. It’s not predictably critical. More like you are actually trying to come to terms with it all. Amidst the calculus and humor, there is almost a kind of longing in this new work.

JO’C: That’s interesting. I didn’t think of it as longing, but I guess it’s my desire to truly know something. I’m curious about how our ways of thinking and behaving are affected by so many other things—everything, really. Not simply the media or Internet, but our friends’ tastes, the weather, color, sound, etc. And how these experiences then change us and lead us to behave differently. It’s like a metamorphosis. I guess I wish I could see what’s happening to me, or you, or anyone, really. That is serious longing, right?

RH: Yeah, like you’re trying to harness or understand realities that are infinite and impossibly complex and interconnected. It actually makes me nervous.

JO’C: Nervous? I’m always nervous, so … I mean, I think it really is a little scary to think about that vastness of those realities and how our memories are ultimately all we have to rely on—like the fact that every experience immediately becomes a memory. Once something happens, it’s gone. Or it becomes something else.

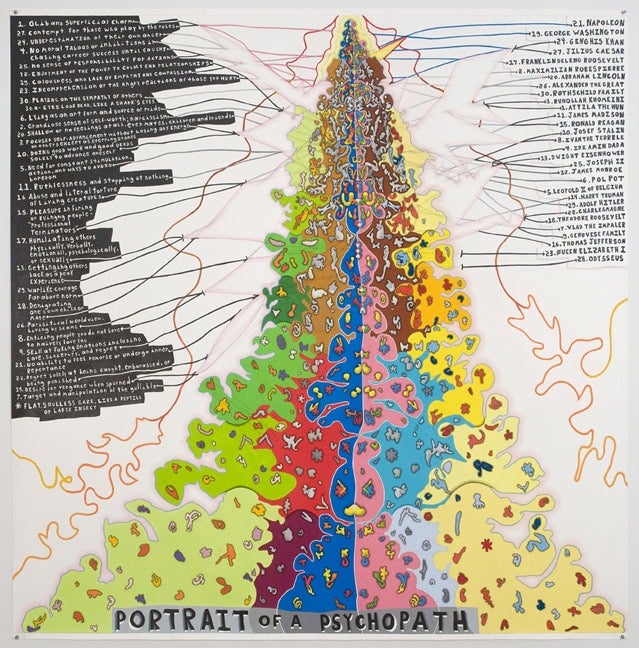

2012. Graphite, colored pencil on paper, 74 x 73 inches.

RH: I love the low-tech nature of your work. Your hand, time, and meandering impulses are central to what you do. Both 2-D and 3-D computer rendering are so common and accessible at the moment, it makes that aspect of your work feel conceptually vital and personal.

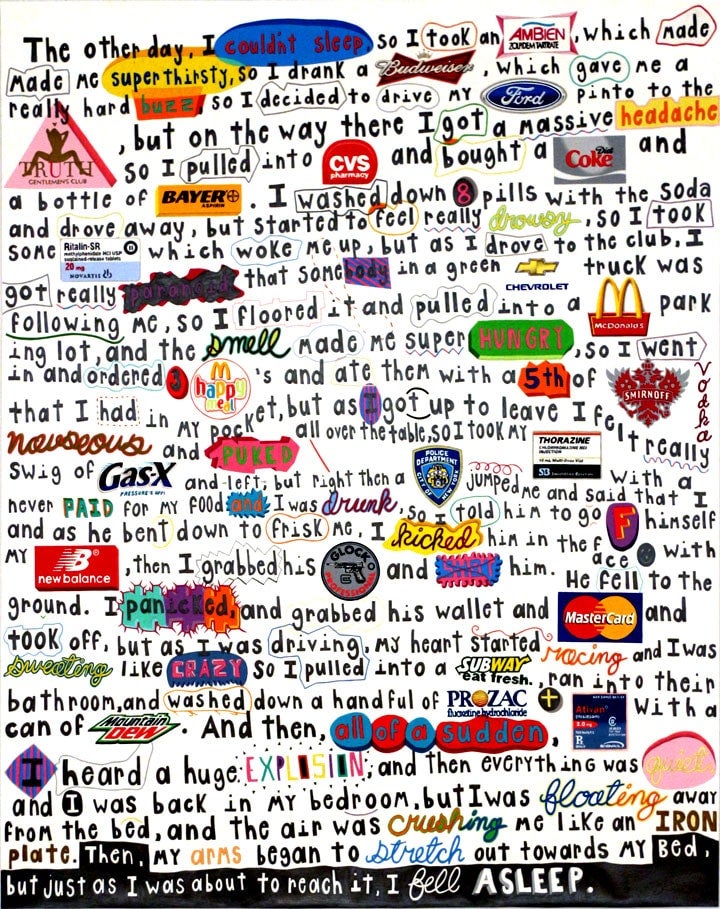

JO’C: I really like the slow process of plotting or charting by hand. It allows the information I’m using to transform into something equally “real” as form. It can take up to a year to finish a big piece. And I’m not looking to translate something from life, as it looks or as it seems, but I do want to try to get at how it ended up looking like it does, or acting the way it does, and create a visual equivalent through those same processes. So for example, with those curse-word drawings (Scumbag) … I was interested in how the offensive things we can say to each other have come to mean what they do, and how the etymology of those words has either given them more meaning, or conversely has made them less powerful. So, instead of using the actual words, I collected a group of the very worst, as voted online, and then split each one in half, and started to reconnect them into “new” words. The results are strange, offensive sounding hybrids—like how a loaded word might transform over time, through its usage. I was thinking that the experience someone might have in reading these hybrid words would be new—they would seem novel and surprising, even funny. But they are derived from truly horrible insults. And how does a word’s meaning change over time? And why are these types of words so powerful? And if you say them 100 times, why does that make them seem strange? The time it takes to make the larger pieces allows for this transformation to happen too, but on a much greater scale, and more gradually.

RH: So, the work becomes more complex visually through your process, but also what it is “about” becomes more expansive. The connections and disruptions you create with logos or shapes around unexpected word combinations … the hand-spun web is more than visual.

JO’C: Yeah, I like that way of putting it. The visual is always the primary thing I’m dealing with, but don’t really talk about much. I love to immerse myself in the patterns and forms of the things I’m thinking about. To see what these things look like is really exciting—what kind of shape I end up making, or where a pattern takes me. I often start by pushing some visual thing that interests me, like a pattern, or texture, or color combination, into an idea I want to work with.

RH: Can you talk a bit about how that color happens? I know that some people with amazing mathematical minds see numbers as colors. Is it like that for you, or systematic in any way?

JO’C: No, sadly I don’t see things as colors. It is usually more improvisational, at least at first. I do love diagrams and things like brain scans, where color is the residue of some physical or mental action. I start with colors I feel like using, and then try to apply them in a way that pulls some logic out of the idea I’m working with—defines it somehow. Like color is extruded through a piece of information or something.

RH: Is it the same for composition and shape?

JO’C: It really depends on how I start. Sometimes I begin in the center and let the forms accumulate compositionally, like an explosion that builds through addition—like the butterfly effect. Other times I’ll start at the edges and work towards the center—a reverse explosion, slowed way down. I’ll usually start a piece with some very specific bit of information, like the temperature of a place, or the location on a map of an event, or a phrase that was used in a speech, or a particular time of day. This tells me something very specific and real about an experience that I can empathize with, but it’s still very abstract. I like this contradiction and try to blow it up in order to see what it looks like. That feels like a life cycle in a way—something is born and dies at a very specific time in the past, and then a new form emerges and grows as I use it. Like reincarnating a statistic.

RH: Does that tie into the sculptures? They have the feel of biology or physics models.

J’OC: Yeah, the newer ones derive from graphs of various things—wealth in the United States, war casualties, the amount of people who believe in ghosts … things that are difficult to quantify. I’m interested in how graphs, which tell us something very specific about human experience, are basically abstract distillations of physical and emotional events. Powerful moments in a person’s life can be tallied into into a simple line on a graph. It may allude to a larger pattern—how we collectively behave or act as humans, for example. I take these graphed lines and redraw them, paint them, cut them out, and connect them into loops. I thought of this as three-dimensionally reincarnating the statistic, which allowed me to see it as spatial, or real again, you know? But I wanted them to be more simplified, because they’re in real space and complex enough on their own, as 3-D forms, without much surface pattern. That felt right.

RH: Interesting to think about why the introduction of paint is important to the text pieces.

JO’C: When I decided to work with those “letters,” I started to draw them, but the drawing process seemed too personal or human. Painting them removed that connection for me, and I started to see the paintings as distillations or excavations, you know? That’s why I painted around the text and left the letters as the base color—it was like they were pressed in concrete, like a handprint on the sidewalk. They then seemed more timeless.

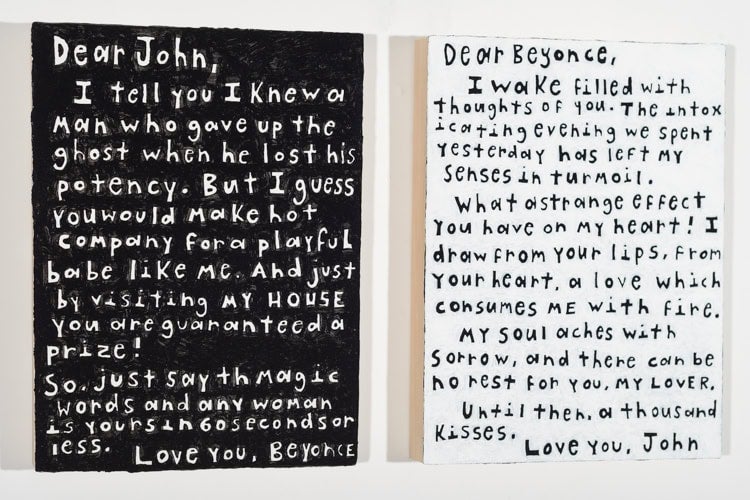

RH: I could ask you more specific questions about all of these, but it would be great to know about the hot Beyonce exchange.

JO’C: Well, I get a lot of hot spam emails! Some of them seem pretty personal, as if the writers actually know something about me, you know? I was thinking about this type of language. It’s meant to elicit an emotional response. It’s not a type of language that expresses some feeling of the person writing it, but is meant compel the receiver to respond—like the way Cleverbot can understand language patterns and can fool us. It plays off of the Pavlovian responses we have to particular stimuli. Like musical patterns, foods, colors. Our behavior is predictable to that extent.

So, for the first panel, I painted a hybrid spam message that was a love letter written to me, from someone named Beyonce. I was then thinking about how I might respond to her, and started looking at famous love letters from history. I wanted to use a completely different type of language, from another time, that was written by an actual person to another person. So, I found this beautiful letter written by Napoleon to Josephine. I tweaked it to be roughly the same word count as the spam, and then painted it in opposite colors. The back and forth of the paintings was really compelling to me. The space between them became loaded. I thought that this pairing might link the motivations of the two letters, but force a cognitive leap between the past and present that each represents—make one aware of how we have changed. Or not changed at all. Both options are interesting to think about.

I also emailed this letter back to Beyonce …. I never got a response. Too bad.

RH: Can you talk about the self-portraits with sunspots? I really like the connection between self and celestial body, and there is an allusion to disease.

JO’C: They actually happened somewhat by accident. I was trying to make photo portraits and was simultaneously working with images of sunspot patterns. I decided on a whim to push them together. It doesn’t seem that far from Jensen for me, [whom] you mentioned earlier—his pushing together information and systems. I see the portraits as connected to the other works in the show in that there is a powerful force (the sun) impacting the way some other form (my face) actually looks, physically. The patterns are from NASA documentation of the sun’s surface, and my photo is from that same date, so the patterns are linked temporally. I definitely didn’t intend the connection with disease, but they do look like some biological process has wreaked havoc. I started to take the photos of myself as if I were documenting a progression or transformation. I thought of The Fly or Metamorphosis—when I looked at them, it really felt as if something incredibly powerful was controlling me.

RH: So Johnbot, do you see the other works as self-portraits?

Johnbot: It depends on what you mean by thinking. A scar is a buildup of tissue left behind after a wound heals. But I should leave. I have homework.

RH: Who is your favorite artist?

Johnbot: All hail the king! Are you the him?

RH: Do you think the Red Sox will win the World Series?

Johnbot: Why would I think the Red Sox will win the World Series?