One fateful day in 1989, artist Lucas Blalock suffered a childhood injury at Walt Disney World’s “Pirates of the Caribbean” attraction. His thumb was crushed while on the ride, and he underwent an experimental surgery to replace the crushed digit with his big toe. Thirty-two years later, Blalock returns to this freak accident in two solo exhibitions: Florida, 1989 at Galerie Eva Presenhuber, New York; and Lucas Blalock in T-E-L-E-P-H-O-N-E at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Abroms-Engels Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA).

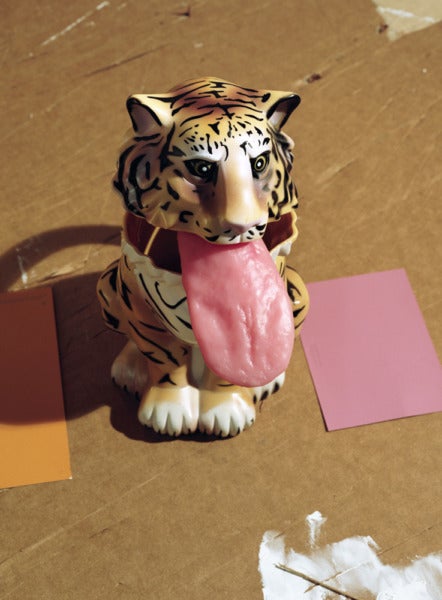

Between the thumb accident and these exhibitions, the Asheville-born artist has become internationally renowned for his highly manipulated and bizarre photographs, which start as large-format photographs before undergoing a series of distortions, overlaps, and cuts in Photoshop. The resulting images are printed at large scale, filling a gallery with their warped, technicolor sensibilities. Many of Blalock’s pieces are somewhere in between a still-life and an unnerving visual gag. His depictions of inanimate objects and the occasional landscape are interrupted with served body parts, man-made textures, and other digital aberrations––a literal Frankenstein’s monster of pictures, illusions, and methods. In the AEIVA exhibition, Hole Foods/Kissing Booth (2018) depicts a photographic overlay of a plastic bag, with photoshopped holes revealing the Laffy Taffy pink tongue that lies beneath the bag’s surface. On view in the New York presentation, Blep (2020) revisits the tongue motif through a photograph of a tiger figurine with a comically large––and human––tongue hanging from its mouth.

Outside of the literal fragmented limbs, tongues, and fingertips that populate his work, Blalock’s photographs contain a sense of disembodiment and separation from the human form. Take, for instance, the lone self-portrait in T-E-L-E-P-H-O-N-E, The Guitar Player (2013), in which Blalock’s face appears in split perspective with his shoulders and torso fragmented through digital manipulations. Blalock has offered numerous reasons for the abstraction in his art, and he has previously described it as a way of showing the “post-production” that goes into photography.[1] But for this behind-the-scenes look at his work, there is also an element of separation that Blalock creates that calls back to the avant-garde art of the early twentieth century. In numerous interviews, Blalock mentions the work of German playwright Bertolt Brecht, particularly in terms of his writing in On Theater about the presence of labor in a theatrical production. By bringing Photoshop and photo-editing techniques to the forefront, Blalock’s considers “the kind of labor that [he] was doing and how [he] might bring this labor—as [Brecht] did—into the production.”[2]

There is another über-Brechtian aspect to Blalock’s work, though. In a 1964 essay, Brecht describes Verfremdungseffekt, which translator and editor John Willet, attempts to parlay into English as The Alienation Effect, but has also been called the Distancing or Estrangement Effect. Verfremdungseffekt is defined as “playing in such a way that the audience was hindered from simply identifying itself with the characters in the play”[3] which is best exemplified in Brecht’s productions of The Caucasian Chalk Circle and Mother Courage and Her Children. Audiences are accomplices in the on-stage drama without being allowed to easily relate to the characters and their actions on a subconscious emotional level. The prominence of Photoshop in Blalock’s photographs already accomplishes an emotional distance of sorts. In some of his works such as The Covered Piano (2015-2016), the editing techniques obscure the basic image to the point that the viewer must work to determine what one is seeing in the first place. This concealment and amount of attention required on the part of the viewer paradoxically draws one into the scene through careful looking and a strange sense of emotional distance from the photograph’s subject––a tricky balancing act that requires true artistic talent on the part of Blalock.

We can look at Blalock’s Florida, 1989 exhibition as a Brechtian confrontation of his childhood in which the viewers of his work are kept at arm’s length from the emotional fallout of the Disney World incident while allowing for reflection. The entire event was understandably terrifying for Blalock: it created a pre- and post-incident divide in his memory, and according to the artist, the trauma of the incident triggered early onset puberty. And while Blalock cultivated a successful career in the arts in spite of all this, it feels natural for the artist to return to this pivotal moment with the uneasy, Brechtian distance that defines his artistic practice. “The Pirates of the Caribbean” ride, with its clunky, humanoid automatons and endlessly repeating recreations of events that never happened, exists in the same uncanny valley as Blalock’s work on the whole. He photographs pieces of animatronics in Squirrel, multigraph and Rubber Dog Toy Insides, multigraph (both 2020), which appear in multiples in the image through a compositional trick mirror. For Reverse Titanic / Hell is in the Air (2019), two rubber fish are placed in a near-ouroboros, conjoined at the mouth and eating each other, perhaps an allusion to the cyclical nature of memory or at the very least, the repetitive, creepy ride that started the chain of events that continues to reverberate throughout his life and career.

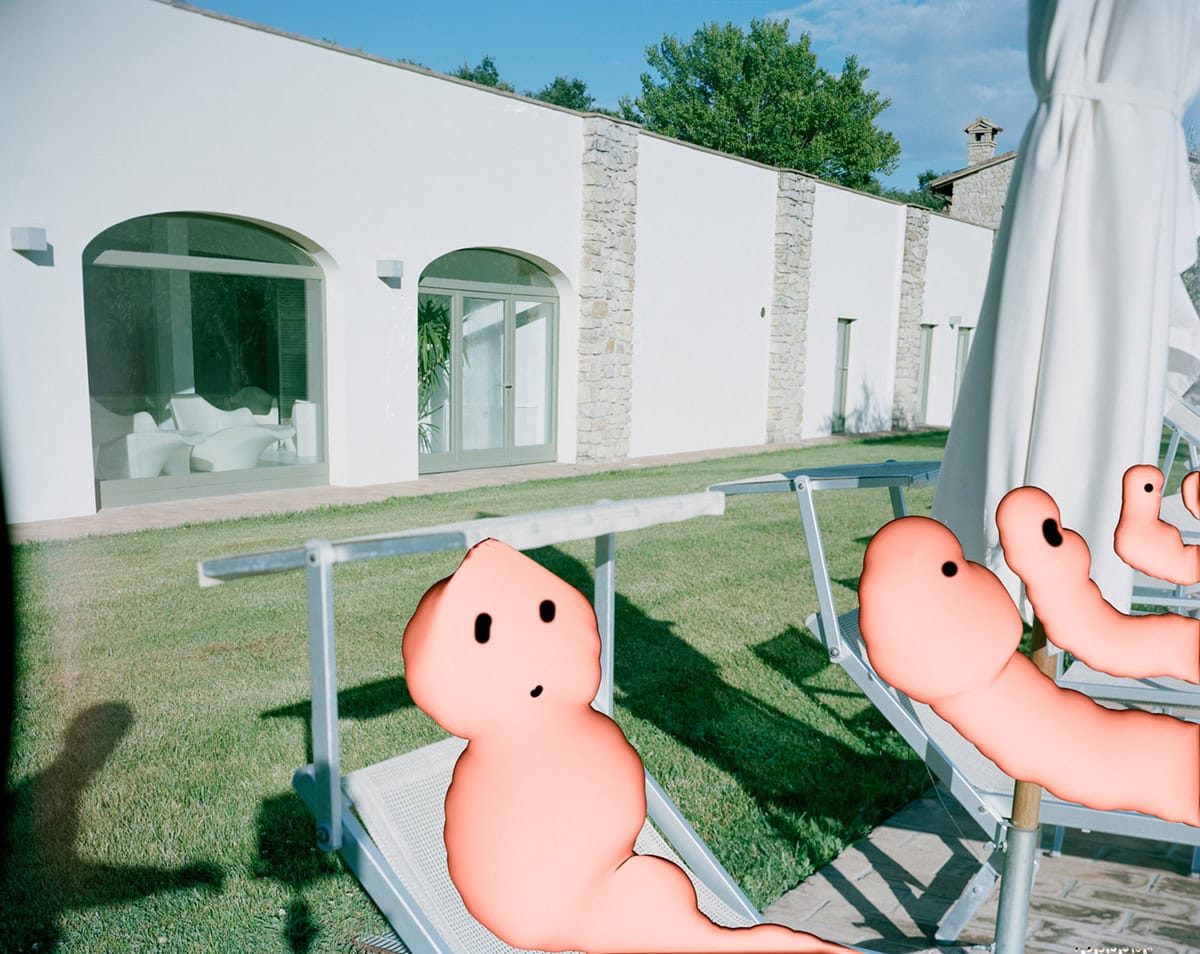

The titular piece in Florida, 1989 most clearly represents the alienation that Blalock uses to explore this event. The photograph depicts a poolside scene in which people sitting lounge chairs are completely obscured and replaced with sunspots that look like worms with demented, smiley faces. The only remnant of human life is the shadow of a person at the bottom-left of the composition, leering over the grass. Although this is clearly a scene of some sunny Florida vacation––perhaps the fateful vacation in which Blalock lost his thumb––there is no sign of leisure or ease, not even a friendly human countenance to relate to. It remains a mysterious, Lynchian scene: familiar enough to analyze, but still too strange to extract any real meaning from. Florida, 1989 and its counterpart T-E-L-E-P-H-O-N-E are not about producing conclusive images of trauma for the viewer, but that makes it all the more compelling, messy and real. Blalock does not have easy answers to explain or understand his experiences. If he did, why would he make art?

[1] Lucas Blalock and Taylor Dafoe. “Lucas Blalock by Taylor Dafoe.” BOMB Magazine, May 4, 2016.

[2] Lucas Blalock and Charlie Schultz. “Lucas Blalock with Charlie Schultz.” The Brooklyn Rail, March 2018.

[3] Bertolt Brecht, “Alienation Effects in Chinese Acting,” Brecht on Theatre. Edited and Translated by John Willett. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1964), 91.