The result of a six-month residency with the nonprofit Dashboard, Christina West’s current installation at 186 Mitchell Street in Atlanta’s South Downtown combines video, architecture, and sculpture to offer an extended examination of the nude male body. This shift in focus from the traditionally male viewer-auteur to the male viewed subject is a timely recalibration of art history’s long-held and still-dominant male gaze. Yet Looking at a Naked Man also remains in dialogue with the centuries-old art school practice of drawing from male life-models—a practice from which the academy excluded women artists into the twentieth century—that traces its lineage back to classical Greece and Rome and those cultures’ privileging of the masculine form. Though any act of looking at (and representing) a naked man might in this sense be considered classical—and perhaps therefore traditionalist—I am interested in the playful and subversive ways in which West uses the art and myth of ancient Greece and Rome both to unpack the performance of male identity (or of any gender) and to challenge our complicity in that performance by exposing the absurdities and anxieties of our own act of looking.

The former barbershop at 186 has been transformed into a labyrinth of corridors and partitioned rooms punctuated by windows and doors, some more like secret peepholes, others only giving the illusion of access to hidden spaces beyond. That we are as much the subjects of Looking as West’s male model is made quickly apparent as viewers approach a pair of disembodied plaster legs stood in front of a mirrored doorway. Recalling the museum-display of fragmented Roman sculpture, they parody popular culture’s fetishization of body-parts, and of legs in particular—from the muscle-building fanaticism of men’s health magazines to the destructive thigh-gap obsessions of Instagram. Though cast from West’s model, it is our body that completes the mirror-image to walk the space in his “shoes,” suggesting that we, too, might be nothing more than the sum of our physical parts. Peering into one small window likewise brings us face to face with our own reflection, turning us from would-be Peeping Tom into Narcissus, the hapless youth of Greek myth who was so captivated by his own (unrecognized) reflection in a pool that he wasted away, unable to break his own love-struck gaze.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. no. 9383.

Photo: Egisto Sani via Flickr.

Popular in Roman wall-painting, the best-known ancient telling of this myth is by the Augustan poet Ovid, who emphasizes the dangers of misdirected looking (and lusting), and of an obsession with surface. The (self-) absorption of Ovid’s Narcissus with his own image—and his failure to understand it as such—has also been interpreted as a metaphor for the desired effect of naturalistic art on its viewer. But for West, the myth seems instead to expose our troubling need to always be the subject of another’s desirous looking, even our own. In a video played on a screen suspended from the ceiling and reflected in a mirror on the floor, West’s model circles another mirror, crouching on all fours and bending low to meet his reflection, seemingly entranced. The footage, however, has been shot closely from behind the model’s shoulder so it is not always certain that the man who faces us is a reflection; this might be an encounter between two distinct lovers, suggesting that the Bergerian frisson of self-objectification imposed on female art-subjects might belong to men, too. It even extends to us, leaning too close to find a clearer angle, and catching our own eye looking back.

Although the movements of model and mirror-image border on the erotic, they are combative, too. They are as much like wrestlers as lovers: their intertwined bodies recall the appearance of a Roman marble sculptural group from the first century CE known as the Uffizi Wrestlers, which depicts two naked youths with taut, muscular bodies engaged in a form of hand-to-hand combat known as the pankration (literally meaning “all power”). This dangerous sport, one of the events held at ancient athletic competitions like the Olympic Games, was considered the ultimate test of strength, technique, and endurance—so much so that it was said to have been invented by the mythical hero Hercules, the original body-builder and World’s Toughest Man. The Roman marble statue probably copies an earlier third-century BCE Greek bronze that commemorated the winner of a pankration competition and, as such, offers a model of ideal manliness that is macho, aggressive, hardened, and victorious. West’s image is less idealizing and more unsettling: intimate camera-angles reveal soft flesh, body hair, a flaccid penis, and a wrestler trapped in a love-bout that can never be won.

The Uffizi Wrestlers were found in the ruins of an imperial pleasure garden in Rome known as the Horti Lamiani. These gardens also contained a second-century CE marble statue of a nude discus-thrower (the “Lancellotti Discobolus”), which is a Roman copy of a famous (though now lost) bronze statue of the same subject made by the Greek sculptor Myron in the fifth century BCE. Like the Greek original of the Uffizi Wrestlers, Myron’s statue commemorated the victor of an athletic competition and would either have stood in the sanctuary where the games took place or in the triumphant athlete’s hometown as a permanent memorial to his success. Rather than a portrait of the individual winner, it, too, offered its viewers an ideal body to emulate and admire. Embodying strength, poise, and lithe athleticism, the statue was celebrated in antiquity as a paradigm of masculinity—equating physical beauty to mental rigor and moral virtue—and has remained a metric of such ever since. In the second century CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian had a marble version set up in his villa at Tivoli outside Rome (the “Townley Discobolus,” now in the British Museum in London), where it signaled his appreciation of Greek culture but also his more carnal admiration of the male form. We might think of the Discobolus and wrestlers on display in the Horti Lamiani as similar set-pieces, providing gender archetypes as well as models of Greekness: the emperor Caligula is said to have acted in plays in the gardens, code-switching and cross-dressing to impersonate gods, goddesses, and Greek heroes.

In the twentieth century, Myron’s Discobolus was alternately recast as the Nazi Übermensch, brought to life in the opening scenes of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), and as the ultimate heartthrob, embraced by Marilyn Monroe in a series of photographs taken by Milton Greene in 1956. But through the lens of West’s camera, the “Discobolus”becomes an image of failed masculinity—or, rather, of the failures of the hyper-masculine identity its honed features and balanced proportions have come to represent. In the central room at 186, a looped video played on a large screen shows West’s model attempting to hold the statue’s stance – a pose which was, in fact, not based in reality but fabricated by Myron to be a perfect embodiment of grace, torsion, balance, and symmetry, and hence completely inimitable. At once funny and frustrating, the model’s struggle reveals the restrictive standards and at times ludicrous performativity of gender. His persistent attempts to re-strike the discus-thrower’s pose despite obvious discomfort border on the masochistic, positioning viewers less as voyeurs and more as arbiters of his suffering.

This, in turn, brings the film into dialogue with Bruce Nauman’s video performance Walk with Contrapposto (1968). Here, as Ruth Burgon has argued, Nauman’s adoption of another classical pose, the hipshot contrapposto stance used for most standing sculptures from the fifth century BCE onwards, exposes bodily control as a form of social confinement. Repetitive movement represents a kind of incarceration in Nauman’s work, exercise a means of discipline. Seen in this light, West’s Discobolus is more an indictment of a conformist society’s rigid coercion of body and mind than a depiction of the (non) attainment of physical perfection through bodily training.

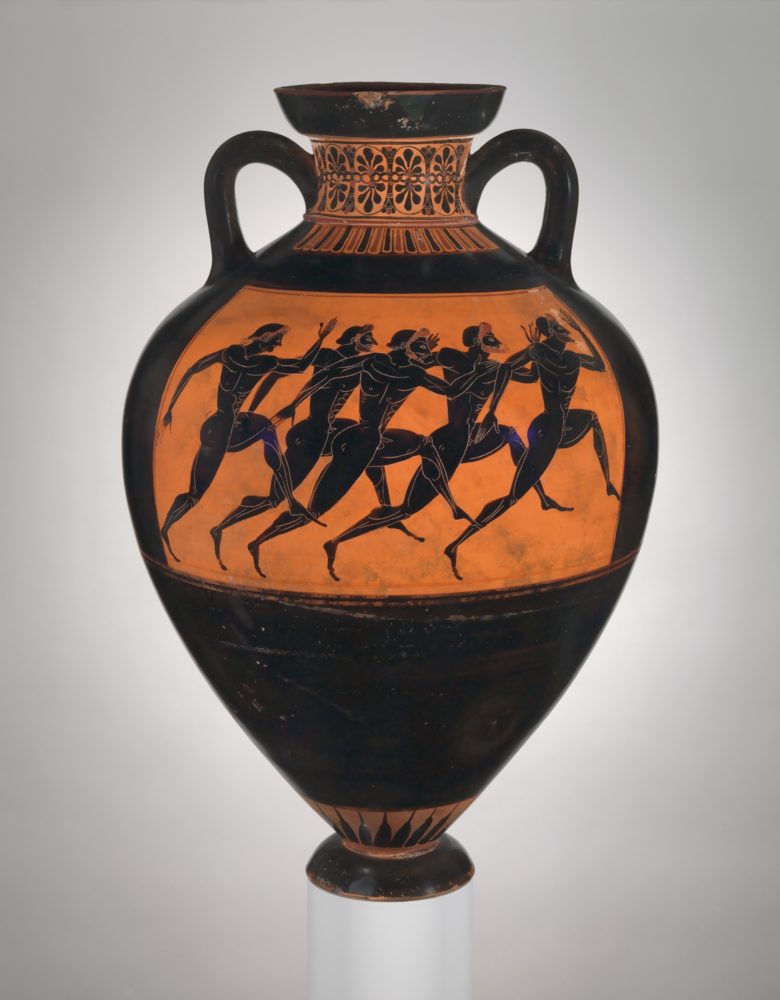

The futility of the model’s efforts to embody the Discobolus are replicated in a third video. Projected on the back wall, West’s model runs repeatedly towards the camera—and us—bringing to mind images of nude runners depicted on Greek vases. These were given as prizes to the winners of the sprint races at ancient athletic competitions, but here there is no race, no destination reached, no competitors defeated. West’s model runs alone, retracing his steps and adjusting his gait over and over again. This is more like a military exercise or prison drill, and the model’s nudity speaks less of masculine triumph and inviolability, as in Greek and Roman art, than the pliability and ordinariness of a body-in-training. But as in the classical nudes that West evokes throughout the installation, whose agency depends on their being seen, this is also a body acting under surveillance: we are an acknowledged observer of its monotonous performance. Elsewhere in the show, we are given intimate, unnoticed glimpses of West’s model at rest, or in a tangle of sheets, acting out the mundane rituals of daily life. But here, as in another video where the model performs a series of press-ups, he seems to watch us watching him. If West’s contention is that the practice of masculinity is predicated on rehearsed posture and honed physique, then it also seems to rely on that posturing being witnessed. Yet confronted by her naked man, whose mirror-image we already worry we might have become, we are no longer sure who is looking and who is being looked at.

Presented by Dashboard at 186 Mitchell Street SW in Atlanta, Christina West’s installation Looking at a Naked Man is temporarily closed to the public due to concerns about the COVID-19 outbreak. Dashboard plans to reopen the installation in the future.