Learn about your coworkers: how they live, who they live with, what they care about. What they like to do in their spare time, what their aspirations are for the rest of their lives.

Roughly one year ago, workers at the New Museum formed the New Museum Union, catalyzing the movement for museum workers’ rights across the country. Last September, as part of Burnaway’s “Art and Labor” series, I wrote an essay for the magazine that explored art workers’ unionization efforts and the history of right-to-work laws in the South.

In January, two founding members of the New Museum Union provided an update on where the group stands a year after voting to unionize. Lily Bartle and Dana Kopel—both of whom served on the union’s first contract bargaining committee—spoke with Burnaway about the museum’s campaign against the union, the process of winning a first contract, and what they and their coworkers won.

Ben Beckett: When you were first organizing, how did you know you were ready to approach a union office?

Dana Kopel: We had been meeting for nearly a year when we approached the local union. It started with just, like, five people over lunch and had gradually grown to include a fair amount of the staff meeting over drinks, just to talk about what wasn’t working and what we wanted to change and how we might go about doing that. At a certain point, the idea of a union had come up a number of times, but I think most people—myself included—just didn’t know what the process or benefits would be.

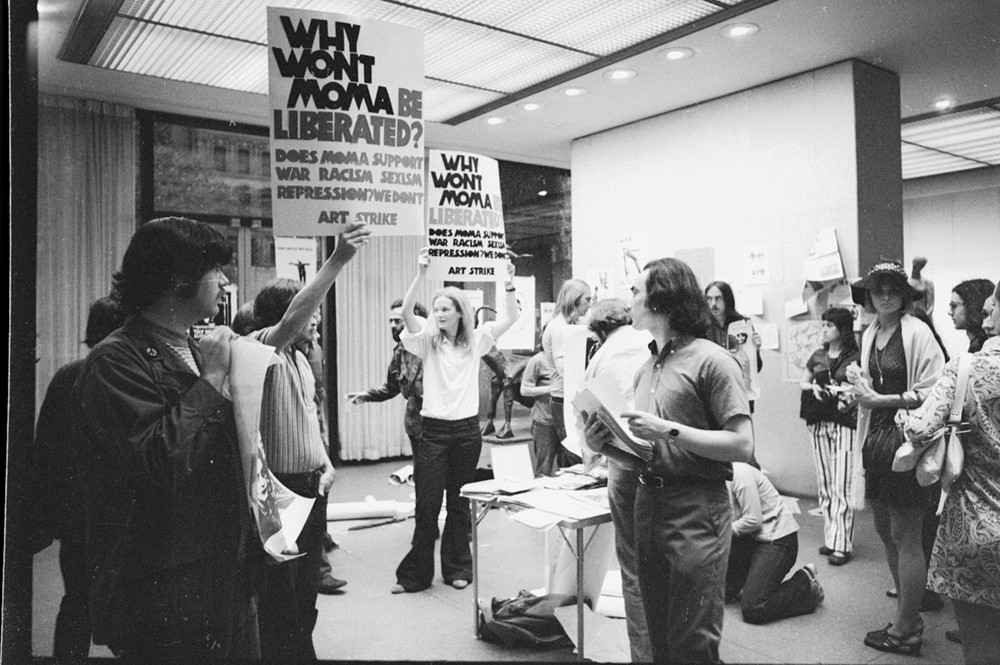

So, through a friend, I reached out to Maida Rosenstein, the president of Local 2110. We scheduled a meeting with her and some stewards from MoMA and got about ten people from the New Museum there from a lot of different departments. Some of the stewards from MoMA—where they’ve been unionized since the 70s—passed around papers with their salaries, and they were really jarring to look at for everybody.

Lily Bartle: That was a moment of almost unanimous radicalization, or at least consciousness-raising.

DK: The closest position to mine was making almost double my salary. Maida and the MoMa stewards left and we asked everybody [from New Museum], what do you think? And they all said, yeah, let’s do it.

LB: Before that, we had considered a number of options—writing an open letter, doing some kind of staged action. But Maida made it very clear in a very convincing way that the union would be the only way to make permanent, lasting changes to our terms and conditions of employment.

DK: What felt really special and heartening in those conversations was that everyone was really invested in making the museum a better place to work for people who came after them. That felt like a really powerful way of undercutting this careerist individualism that’s so present in the art world.

LB: Right, making sure your position is tenable for whoever comes and takes it after you. It’s something you don’t really think about when you’re in the art world and you’re moving jobs like every eighteen months.

BB: Tell us about some of the material gains that you made with the contract and about what rights you have on the job now that you didn’t before.

DK: One of the really huge gains was just cause. That means they have to have a legitimate reason to fire you. That provides so much job security.

LB: Especially for an industry that is really personality-based and focused so much on individualism. The notion of just cause is really important in terms of ensuring a diverse workforce.

DK: Increased salaries were also a huge win. When we started organizing, full-time staff at the lowest end were making $35,000 a year.

LB: When that started to get into the press, they bumped those people up right away because they realized what bad press that was.

DK: They hired a new person at an entry-level position at $40,000, which is still not a livable wage. They told us that, according to their research, a living wage in New York City was $51,000 a year.

LB: That was something they said to us in a captive-audience meeting. So we were able to continually bring up this figure of $51,000 a year.

DK: So we pushed for $51,000 as our bottom line up until the last minute. And we really had to compromise. Now the lowest full-time salary is $46,000, but that is still an $11,000 a year increase. I think one of the other huge wins is the pay for people working in visitor services and the store, who are now making $18 an hour and have a raise structure in place that will bring them to $22 an hour by the end of the contract. That felt really massive and really important.

LB: Healthcare contributions from the museum also went way up.

DK: My healthcare contributions are roughly halved from what they were. The change is even more substantial for people who are being paid less.

LB: Maybe the biggest win of the contract is now having an actual structure for filing grievances at work. We had no HR person until we started to put public pressure on the museum—that was when they finally decided to hire an HR person.

DK: Now we have a grievance procedure that ultimately, if it’s not resolved, ends up in arbitration with a neutral third party arbitrator. So there is a binding structure for resolving these things. We also have a non-discrimination clause that, among other things, offers protection against discrimination based on union activity.

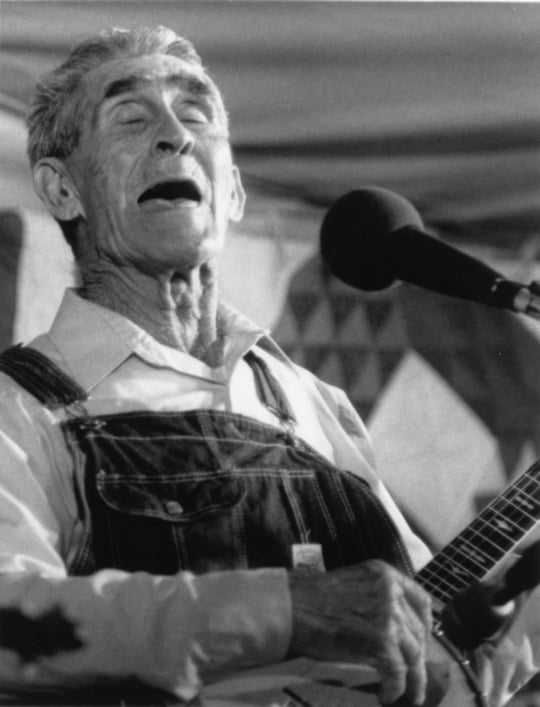

Photo by Dean Kaufman.

BB: Can you talk about how you prepared to come to the bargaining table?

LB: Our bargaining survey was really important. That was basically right after we had the bargaining committee elections, or during the process, the organizing committee drafted the bargaining survey.

BB: What is a bargaining survey?

LB: It’s a survey that asks questions about people’s salaries, their day-to-day life at the museum.

DK: Their workspace, their healthcare, their experience with grievances and workplace issues. We had a basic structure that we got from the local, and then we were able to build that out to address particular issues and questions that we knew people at the museum were dealing with.

LB: Like, for example, have you ever been discouraged from reporting overtime? This gave us really important anecdotal data we could use in bargaining, because the museum would continually try to undercut us by suggesting we didn’t have any factual basis for our complaints, claiming that there wasn’t any proven need for the things we were asking for. So the data we got from the survey was really important.

BB: How did the museum push back against members of the bargaining unit after you started the union?

DK: Some people experienced more direct interpersonal retaliation from their managers, who would refuse to speak to them even about work related things, or people’s access to certain programs that they needed to do their jobs was either taken away or severely restricted.

LB: Also denying people overtime.

DK: Which is a huge part of people’s jobs.

LB: And a source of expected income for a lot of people who are on the lower end of salaries in our unit.

BB: How did you keep united?

LB: A huge part of staying united was this demonstration we organized over the summer. It wasn’t [legally] a picket line, but we decided to stage a protest outside of the museum on the night of one of the openings. A lot of people from the union and a number of people from affiliated unions and organizations came to support us, and that was really incredible. We had over a hundred people there.

DK: It was really powerful, and some people refused to go into the museum. It made it clear to a lot of people exactly why we need a union, and made it clear to them who was looking out for them, that we’ve been looking out for each other in a way that management hasn’t and won’t.

BB: What effect did the demonstration have?

DK: It definitely had an effect on bargaining. The proposals they were giving us and their responses to ours were still pretty hostile and reductive before the demonstration. They changed once they saw how much power we had behind us—how much of the staff was ready to fight.

BB: After the demonstration, what steps did you take next?

LB: After the demonstration, we started organizing for a strike. The museum was giving a little but not giving what we needed to get to where we wanted to be when we wanted to get there. So we started mobilizing and organizing for a strike, and that created a lot of solidarity between members.

BB: What does it look like to start organizing for a strike?

DK: You just start talking about it. You gauge where people are at because you want it to be something people feel more or less comfortable with. You also want people to know it’s a tool. I don’t think any of us actually wanted to go on strike. A strike is something you use as a last resort. I think it’s important to convey that sort of strategic rationale, but also to get out details about what would happen in the event of a strike: how would you be supported by the community, how would you be supported by the UAW, what would happen with healthcare. Those are all things you have to get information out about because people’s lives depend on that.

BB: What was people’s response?

DK: In general, people were supportive. Our strike vote was like 96% yes, so I think people understood the necessity of it, and that definitely helped us in bargaining. Obviously people are scared and have reservations about whether they’ll have an income, which is totally understandable.

BB: What role did the UAW play?

DK: I think for us the help of a local union was so important because there is very little union presence in museums. I don’t think any of us had direct experience with this before. For all of us, it was our first time in contract negotiations, our first time union organizing.

BB: So you had a strike vote with 96% support. How did things change at the bargaining table after the strike vote?

LB: It was really intense after this strike vote, which was incredible and so amazing, something we weren’t even anticipating.

DK: We knew we wanted a strong yes, but that was, like, a really successful strike vote. After that, people’s concerns about a strike came out, along with their concerns about their own positions within the contract. It’s a lot to manage while you’re also in these long days of bargaining.

LB: We went in and were really confident. Basically the first thing the museum side said was, so we’ve heard you guys have been bullying people into voting for a strike. That really undercut the confidence and leverage we thought we had going into that session, and we fell apart. That was really hard.

DK: It’s those moments when things are hardest that solidarity is most important, and you learn what solidarity actually means. Communication is really key. You elect a bargaining committee, that means you have to put trust in them to make decisions. That is something I want people to know. You are choosing your bargaining committee trusting that they will make every effort to get as good and fair a contract as possible. There’s going to be a lot of effort to weaken your power, and it’s those situations where solidarity is really tested and you really need to communicate and show up and trust the people you’ve entrusted with these roles.

LB: We were doing the best that we could to communicate with the rest of the unit. We were sending out regular bargaining updates and side-by-side comparisons of our proposals and the museum’s.

BB: Can you say, in general terms, what some of the tactics the museum threw at you across the table were?

DK: They would suggest we had no agency in the situation, like it wasn’t a choice that we made, like the union was a third party that was trying to exploit us. And we were sitting there like, we know who’s trying to exploit us.

LB: It’s you guys!

DK: We’re all in the art world—we’ve read some Marx.

LB: There was also a lot of blatant sexism from the museum side. They refused to listen to or acknowledge women who were speaking in bargaining and would often redirect questions to male members of the bargaining team.

DK: We had two men on our bargaining team, one straight man, and what he said was always taken the most seriously.

LB: Basically things would always be at a standstill until John was able to produce some comment that would move negotiations further.

We’re all in the art world—we’ve read some Marx.

BB: What happened next?

DK: We did a social media campaign around this time that involved a lot of artists, writers, and theorists—including some people who had worked for the museum before and were very well respected in the art world—speaking out in solidarity and pointing to specific concerns we were fighting for in the contract. I think that definitely helped because the museum really didn’t like its public image being tarnished. The museum wanted to keep this as internal as possible and silence us as much as possible.

LB: The kind of wave of unionization that happened afterwards in the art world really kept us going and reminded us that there was a kind of bigger cultural shift happening that we were helping to usher in. All these other museums and institutions organizing helped us keep an eye on the bigger picture.

DK: That meant so much to me, to come out of a really shitty bargaining session and have an email from somebody at an institution saying, hey, could we talk about this? It’s so helpful to be reminded that this isn’t just the eighty-five of us at the New Museum: it’s a movement, and it’s changing a really exploitative culture. That’s a long process, but there are so many people who are committed to doing it. It’s really, really special.

BB: Say more about how you felt after you settled the contract.

DK: It was fucking crazy. It’s such a weird combination of this feeling of accomplishment and pride, and also disappointment. You’re never going to get the contract you want. I don’t know, it’s like we’ll never get the contract we deserve until there’s full communism.

LB: Speaking to that point exactly, there were certain aspects of the bargaining process that put certain larger political struggles into perspective, like Medicare for All, for example. We really understood the impact that something like Medicare for All could have had in bargaining. It was insane! If we had not had to negotiate over healthcare and we had been able to focus all of our energy on negotiating over wages, it would have been a completely different contract. Coming to the bargaining table makes people’s priorities really clear. As disappointing as that was, it was also extremely empowering and motivating.

BB: What would you say to other museum workers who are considering starting a union?

DK: Do it!

LB: Do it, like, right now, don’t wait. I have no regrets. My whole life fell apart but I still have no regrets.

DK: Same. It feels really good to know that I played a part in creating this structure that will continue to benefit people. Be prepared to have a hard fight. I don’t think everyone will have quite such a hard fight as we had. As employers become more aware of labor organizing in the art world, they are going to become more prepared to put up a more sophisticated fight than we faced. We faced a hard fight but not a sophisticated one.

Get a therapist if you can afford it. Show up for your comrades, for your coworkers. Take care of each other.

LB: That was the most important thing. We formed very close friendships with one another, and that was totally indispensable. It was incredible, the amount of support we were able to show each other.

DK: You will burn out as part of this process. It’s a long process and a hard fight. Familiarize yourself as much as you can with the legal aspects of it. Try to set stuff out in advance.

LB: Learn about your coworkers: how they live, who they live with, what they care about. What they like to do in their spare time, what their aspirations are for the rest of their lives. It’s so important to have that kind of information.

DK: It’s important to know what you’re fighting for together. So much of organizing is talking, so just get comfortable talking to your coworkers. Even if you’re one person and you don’t know if anyone else you work with wants to unionize, just start talking to your coworkers and commiserate over what’s not working and think about ways of making it better.

LB: Related to the stuff I was saying about making a concrete connection between what I was doing at the bargaining table and what was happening in a wider political sense around Medicare for All and things like that, the best way to train yourself to be an activist in real life is to democratize your workplace. Start at square one, at the place where you spend the majority of your time. I feel so prepared to be a part of the larger political struggle having been through this process, and it’s really inspiring and feels really important to democratize every aspect of your life.

DK: Obviously there are times that I’ve thought, is organizing within a museum the most urgent thing to do right now when the world is, like, ending? No, it’s not. But this is what I know, and this is a contribution that I am equipped to make. That feels important.

LB: No regrets.

DK: No regrets.

Find out more about the New Museum Union on its website.

Read about how the editors of Burnaway joined the National Writers Union in this essay by Jasmine Amussen.