In July of 2019, the artist Xaviera Simmons issued a call to action to white artists and writers. In response to white art critics who had deemed that year’s Whitney Biennial “not radical enough,” Simmons challenged white artists and critics to do the radical labor that is expected of and taken for granted from artists of color. In the Art Newspaper she wrote,

We need to see, hear and feel a transformative push towards a white radicality in contemporary art, built on a vision beyond the normal confines of art production and criticism—not just in writing but in works of art, in collecting and through constructive language that comprehends radicality when black or brown artists choose to work with it in a material form.[i]

I had Simmons’s polemic in mind the morning I visited the press preview for LAMENT, a song of sorrow for those not heard, a show of photographs by Linda Foard Roberts at SOCO Gallery in Charlotte.

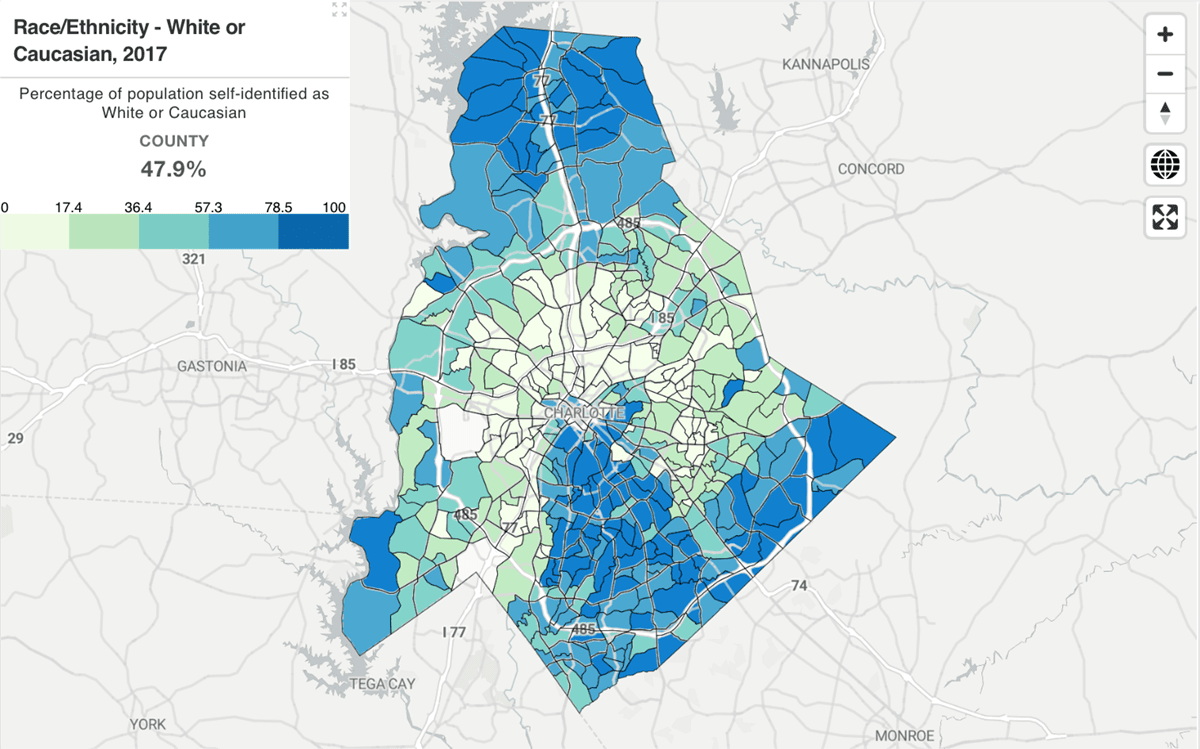

There is a distinct change of scenery on the drive from where I live in North Charlotte to the gallery on Providence Road in South Charlotte. SOCO is located in the part of town known as “the wedge,” a slice of Charlotte that begins at the city’s center and stretches south. It is extremely wealthy, and it is extremely white. In addition to having the oldest and most impressive oak trees in the city, the houses in this area are mostly brick, as opposed to the more economical vinyl siding that is ubiquitous in other parts of the city. Linda Foard Roberts is a native of this part of town, a graduate of Myers Park High School. She now lives in Weddington, a town just south of the wedge.

By all accounts, Roberts is having a moment in Charlotte: she had a solo exhibition at the Mint Museum in 2020 and is currently on view there in two separate exhibitions. Last year, she received a Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship—a grant that awards artists between $30,000 and $45,000 to support their work—for her LAMENT project. Inside SOCO, I’m given a press packet with an exhibition statement that frames the project thusly:

The artist began the work after her son revealed that they had been sitting in the same balcony church pews that had held those enslaved, 160 years before. The significance of not seeing what lay so clearly before her and the words “silence is loud” weighed heavily on her. With LAMENT, Roberts tries to acknowledge and confront the grievous history of the South, where she was born and continues to live.

Roberts calls herself “a recorder of tangible moments” who is “documenting places that are remnants of this history before they slip through the course of time.”

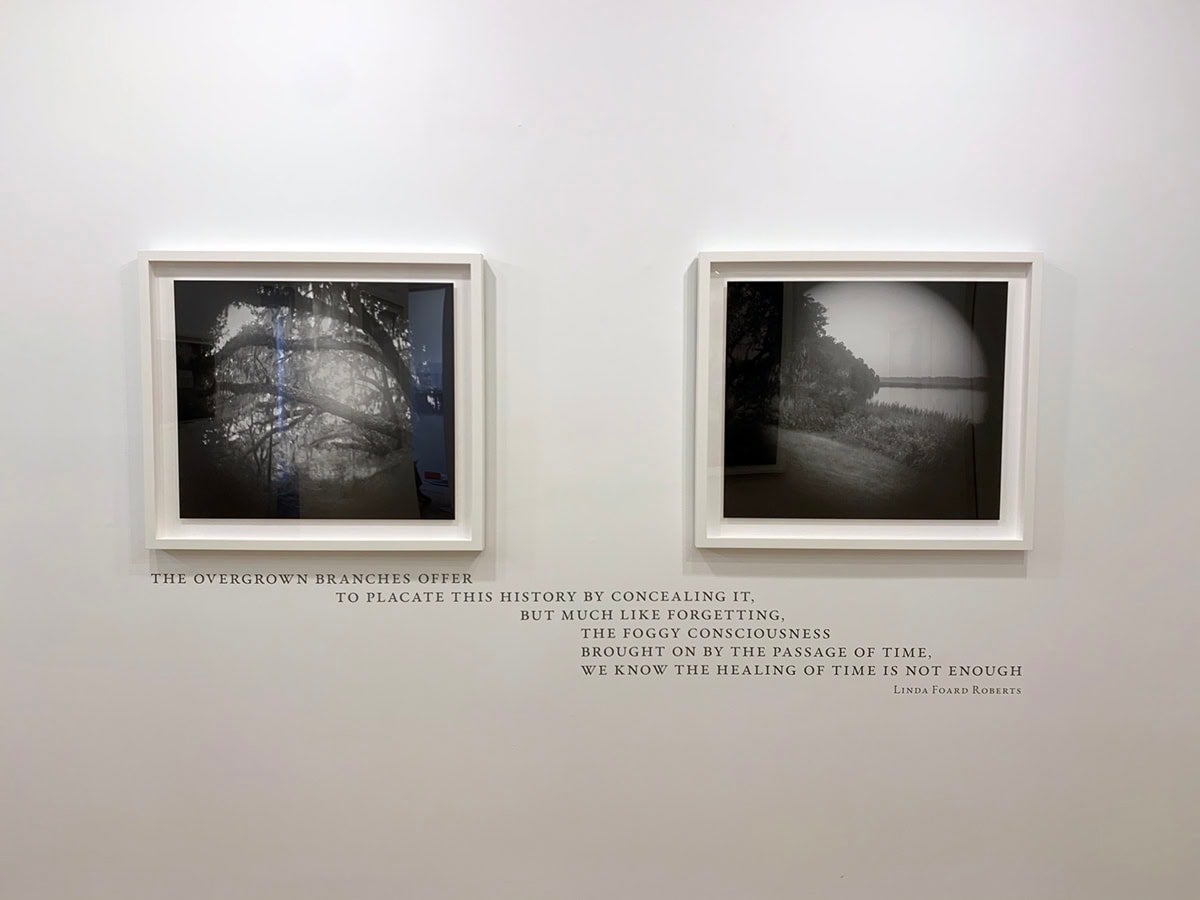

I move around the small gallery, looking at the resulting pictures—black-and-white, large-format photographs of Southern landscapes—while weaving between members of the Charlotte art press, all white like me. The subjects of the pictures are familiar: southern landscapes, a white cabin, lots of “weeping” trees, a country church. I feel as if I’ve seen this shack a hundred times before, in black-and-white pictures stretching from Charleston to New Orleans.

The rural South and, specifically, environments connected to chattel slavery, have long been the subject of white photographers. This fascination began in the 1930s when the Farm Security Administration (FSA) dispatched photographers to document rural America. Since then, generations of white photographers including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Clarence John Laughlin, and Sally Mann have returned to photograph these plantations, churches, shacks, and trees. These sweet little clichés have proven to be endlessly lucrative, and the fetish for plantations has sustained the careers of generations of white photographers, fueling its own small industry of artists and galleries and collectors.

To make the photographs, Roberts used an 8×10 camera and a Darlot brass barrel circle lens, the type that was made soon after the Civil War. The camera and lens give the pictures a shallow, soft depth of field, and a dramatic light falloff around the edges. Sally Mann, perhaps this country’s best-known Southern photographer, has been photographing slavery landscapes since the 1990s. She takes a similarly nostalgic approach, using a nineteenth-century wet plate process. Mann has said that shooting this way enabled her to create photographs with “the appearance of having been torn from time itself.”

There are no wall labels in the exhibition. We’re provided no names, no locations, no dates—we have nothing to tether them to reality. Instead, there are quotations sprinkled along the gallery walls, including, “I was blind but now I see, I was blind but now I see, I was blind but now I see—” from “Amazing Grace.” The somber pictures float around the room, punctuated by platitudes, creating a dreamscape of slavery. The cumulative effect is anesthetizing.

It’s helpful here to bring in the voice of Grace Elizabeth Hale, another Southern white woman and professor of American studies and history at the University of Virginia. Hale takes issue with Sally Mann’s Deep South series and their “watery places [that] seem to float in that blurry space between myth and the world.“[ii] Like Roberts, Mann does not name the sites of violence that she photographs, which include a bridge over the Tallahatchie River—the one where Emmet Till’s body was likely discarded. Hale says,

In not titling these [images], Mann refuses any documentary function. What she is after here is myth. Romanticism alone is too risky. Telling us what these sites are in the world makes visible African Americans killed to achieve southern whites’ dreams of mastery. In giving landscapes of Black loss an aesthetic treatment traditionally reserved for white nostalgia, Mann suggests a kind of artistic reparations. Yet most African American and many white viewers will not need to be reminded of white southern violence. Mann’s Till images seem to do the opposite of what she intends. Rather than “integrating” her Deep South history, they suggest instead a startling lack of attention to African American history and the central place within that past of struggles over the politics of representation.[iii]

To be fair, Roberts’s pictures are lovely! But then, you would be hard-pressed to not get a lovely image when photographing a live-oak tree with a large-format camera. The Southern landscape is beautiful. These pictures will look stunning hanging in any one of these old-money colonial homes that surround the gallery.

“The photographs are installed sequentially and metaphorically,” the exhibition text says, “to move viewers around the gallery confronting this difficult history, towards a place of healing and hope.” Hank Willis Thomas’ Love Rules hangs in the alcove of the gallery, providing convenient closure for Foard’s narrative.

The press is heralded to the center of the gallery, and the conversation with the artist begins.

Roberts leads us around the gallery, giving us insights into the pictures that, because of their conspicuously missing wall texts, we otherwise would not know. Stopping in front of one photograph, she explains that we’re looking at the interior of a freedmen’s church. “This light coming in, to me, represents the subject here of light and hope and that we move in this new direction of love and community.”

The symbolism is not lost on me. Light, or bright whiteness, is a recurring symbol of goodness; darkness, or blackness, is its inverse. I’ve written before about Clarence John Laughlin’s and Dawoud Bey’s uses of light and darkness. Laughlin, a Southern surrealist photographer from Louisiana, used this symbolism repeatedly in his photographs of Louisiana plantations taken in the 1930s and 1940s. The romanticism he imbued in his glowing portraits of decaying plantation homes always lay in opposition to the dark wilderness surrounding the Big House, which he saw as monstrous and foreboding. The trees in LAMENT recall Laughlin’s. And Mann’s. And probably those of others.

During her talk, Roberts acknowledges the missing wall text: “I don’t disclose the places where I photograph, specifically, because I donate to the organization Slave Dwelling Project”—a non-profit organization with the mission to “preserve, interpret, maintain and sustain extant slave dwellings and other structures significant to the stories of the enslaved Ancestors.” SOCO will be donating a portion of sales to the Harvey Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture.

The Q&A portion of the event begins. I raise my hand.

“Linda, one quick question: what is the name of the country church that started this project?”

“Mmm…” her answer ekes out. “I don’t want to say specifically… It’s in Charlotte—it’s on the outskirts of Charlotte—but I try not to disclose because I don’t want any backlash to these places. With some of the things that happen today… I’m sorry.”

I know what she’s alluding to—several plantation and confederate sites have been destroyed or vandalized in the last year. Still, I’m surprised at this decision to not even name the sites that she photographs.

I clarify: “You’re afraid of the church facing backlash?”

“I’m afraid of the church facing backlash for its history—yes. And same for every other place here. I just made a decision early on that it was not about as much of the specifics of where these places are, it was more about this history being still among us, and with us, and the tangibility of this history here. And I’m going to stay with that because I know that there’s been—especially this last year it’s been difficult—things being torn down and I think the history it’s important for us to learn from and preserve it and to remember.”

“Everywhere I go everyone’s really guarded,” she explains. One day, while packing up her car to visit a plantation site, she received a phone call informing her that a building on the property had burned down. “So, from the very beginning I’ve thought, ‘Ok, this is what I’m going to do: it’s not going to be [about] specifics.’ To protect the places, that’s all. I just want to protect them.”

And then she says, “I would hate for anything that I would do to incite anything. If anybody else has an opinion on it”—a few quiet, nervous laughs from the white press—”I’m open.”

Here it is, the cognitive dissonance underlying the show. It’s the same delusion that so many white women have—that we can end white supremacy without hurting any feelings. This unwillingness to incite anything, the reluctance to trouble the waters, confirms her allegiance to whiteness.

With nearly a century of well-intentioned white photographers thinking that representation alone—especially when made Southern Gothic beautiful—might have the power to change hearts and minds, surely the last year has revealed just how much further white women need to go to be truly invested in ending white supremacy. White women’s inability to decenter their feelings and fears and confront racism has been one of the most nefarious forces working against any actual progress. This is a fact writer Lillian Smith keenly understood:

[White women] did a thorough job of splitting the soul in two. They separated ideals from acts, belief from knowledge, and turned their children sometimes into exploiters but more often into moral weaklings who daydream about dignity and democracy and human dignity and freedom and integrity, yet cannot find the real desire to bring these dreams into reality; always they keep dreaming and hoping, and fearing, that the next generation will do it.[iv]

After the Q&A portion of the event, I find Linda to say thank you and goodbye. She asks, again, if I think that she should disclose the locations that she photographs and I reply, again, that I do.

She offers to walk me through the show and disclose the places to me.

I reply that what’s important is putting the information on the wall and empowering visitors with this knowledge.

She sounds her refrain: she wants to protect these places.

I reply that if the exhibition is a “truth-telling project,” then she should tell the truth.

We repeat ourselves back and forth like this, chasing each other in circles. At one point a gallery assistant—a young white woman—decides to weigh in: “I think it was an artistic choice.” The artist repeats her defenses: she’s not interested in specifics; she wants to create a general narrative. I tell her in that case she has succeeded—she has created a myth of slavery. No place exists in anonymity. In a show claiming to be about the tangibility of history, the places cannot become tangible because the artist hasn’t told us where they are. It’s history without facts, an apology without accountability.

Returning to Xaviera Simmons’s declaration, LAMENT lacks any of the “radical impulse” that Simmons calls for. Ultimately, the exhibition says more about the artist than anything else; it is not a historical project, or a truth-telling project, but, rather, it is a personal narrative of one white woman’s feelings about slavery, and it can be summed up simply: sad.

Why are white artists stuck in a trap of re-presenting slavery? We are living in what Saidiya Hartman calls “the afterlife of slavery”—the American plantation system is still tragically relevant. But white artists can’t seem to move beyond this stage of “bearing witness to history” into more original, more imaginative, and potentially more fruitful terrain. Can we fix our gaze on something other than “suffering souls”? Grace Elizabeth Hale reminds us,

Photography, of course, always shows us history as content: every image is in some sense a representation of a moment in the past. But photography can also show us history as form—how the past gives rise to the present and sets up the possibility of the future.[v]

There is a precedent for this kind of self-examining white radicality. Buck Ellison’s tableaux of white families portray the subtle ways in which wealth and whiteness are signaled. Wendy Ewald collaborates with children to create “American Alphabets” and in the process reveals the implicit biases that children hold. Stacy Kranitz’s Target Unknown series creates a speculative fiction of the Nazi photographer Leni Riefenstahl. Roberts is uniquely suited to create, for instance, a project that documents the visual markers of race within and outside of the wedge. Or an architectural index of mini-mansions throughout Weddington—which reminds me of Kate Wagner’s fantastic work of architecture criticism “McMansion Hell.” Other pictures are possible.

Following the exhibition opening, a review of LAMENT was published in Forbes. The white writer begins the article with Linda’s tearful story about her revelation in the church balcony. “People don’t physically appear in any of Roberts’s LAMENT photographs and yet they are everywhere to be seen,” he writes. “Enslaved people. They’re worshipping in the pews. Laboring in the fields. Their songs can be heard. So can their shrieks.” The article ends the same way it began: with Linda’s tears.

In the future, there is a dinner party. The doorbell chimes, and our hostess goes to answer it. She and her guest greet each other warmly, our host taking her guest’s coat as they exchange compliments and niceties. Together, they make their way to the dining room.

Hanging above the long stretch of mahogany table is a large black-and-white photograph of a magnificent oak tree.

The guest remarks at what a beautiful picture it is. If the host has read the exhibition review in Forbes, she might repeat some of the talking points made by that white art critic: “Yes, see how gnarled the branches are? It’s supposed to remind you of the African Americans who were lynched in trees like this.”

Their guests’ eyes will widen, or they will let out a mournful, “oh, wow.” The host will nod solemnly, and then they will return to their salad.

[i] Simmons, Xaviera. “Whiteness Must Undo Itself to Make Way for the Truly Radical Turn in Contemporary Culture.” The Art Newspaper, July 2, 2019. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/whitney-biennial-whiteness-must-undo-itself.

[ii] Hale, Grace Elizabeth. “Signs of Return: Photography as History in the U.S. South.” Southern Cultures 25, no. 1 (2019). https://www.southerncultures.org/article/signs-of-return/.

[iii] Hale.

[iv] Smith, Lillian. Killers of the Dream. New York, NY: Norton, 1994.

[v] Hale.