memory #1

I tend to speak casually about ghosts in New Orleans. Not paying particular mind, when speaking to others from the city about the clichés attached to our home. We know this from that. There are places in New Orleans where the shadow outweighs the substance. Where artifice is indistinguishable from the culture and history that has shaped the reality of our lives. Just as there are those places that remain well outside the gaze. There are the ghost tours, and then there are the ghosts that haunt them. The alleyways alongside the St. Louis Cathedral at certain times of day and slants of light have made the hair on my arms raise since I was a child. Growing up, my mother attended mass or lit candles at the cathedral on specific occasions. My grandmother, when speaking about the French Quarter, always commented on the same things: the Bourbon Orleans Hotel, which had been St. Mary’s Academy, the all-Black Catholic girls’ high school she had attended, and Blessed Henriette DeLille’s (founder of the school’s order) lack of canonization despite all of our lifelong prayers. Marie Laveau’s house was on North Rampart, and the house where my grandfather had grown up on Dauphine. You know it used to be a bad neighborhood, she would say, sadness mixed in with her sarcasm.

City of Dates

I.

“Who’s that? Is that you?” a man asked, gesturing toward his phone, as I sat under the shade of a palm tree.

We were both out early, enjoying the couple of hours outside of the coffee shop before the heat became blistering. That morning I was reading about the growing cultural preservation movement among Afro-Iraqis. Descended from both enslaved East African populations and those of African descent already present in the Arabian Peninsula before the seventh century1, historically, Afro-Iraqis performed much of the labor of draining marshes, cultivating sugarcane, and date farming. I read about Iraq while I waited for my colleagues and a charter bus to arrive. We were heading two hours northwest to Opelousas, Louisiana, to visit the St. Landry Parish Archives with the project Keywords for Black Louisiana, led by Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson, author of the 2020 book Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World. Keyword’s researchers are working to digitize an annotated, transcribed, and translated collection of French and Spanish documents from eighteenth-century Louisiana that focus on the lives of both enslaved and free people of African descent.

The curious man stuck out his phone in my direction, pointing at a square on the California African American Museum’s Instagram grid. There I was in the film still, speaking to the camera on an almost floor to ceiling screen.

“No,” I answered. “People mistake us all the time though. She’s a woman I used to know.”

The white man stared.

I returned his gaze for a second, grateful for the partial obscuring of the palm’s shadow, and went quickly back to my book. I did not look back up again until he left.

The domestication of date palms began in the horn of Africa and Mesopotamia over four thousand years ago.

In his 2015 book Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the Age of Empire, Matthew S. Hopper dedicates the chapter “Slavery, Dates, and Globalization” to charting how the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century demand for dates in the United States fed the trading of forced human labor in Iraq and the Persian Gulf region. The port city of Basra, Iraq, became the epicenter for the trade in both the sticky fruits and humans. Date palms were brought to Spain by North African Muslims and the seeds made their way to the Americas via early Spanish explorers, their crews, and the Black people, enslaved and free, present on those voyages.

Louisiana in the 1730s required slaveholders to record and report when the people they held in bondage ran away. Through both the initial reports and later documents filed in their pursuit, compiled by Keywords for Black Louisiana, I encountered two Bambara men, Vulcan and Antoine (a double amputee), as well as a woman, Fanchon of the Senegal nation, who had fled to Cuba in the summer of 1739. The trio were assisted by another enslaved person, described as a “Spanish mulatress,” in stealing a pirogue and were never seen in Louisiana again. When their whereabouts were sought years later, it was reported that Fanchon had passed away, and that Antoine lived in the woods, while Vulcan sold beer in Havana. I wonder what names they called themselves, each other. What answers they gave the authorities, their neighbors when questioned about their identities.

II.

There is nothing much to say when you are there. All you can do is be quiet and take in the weight—the expanse—of it all.

Visiting Emerald Mound was a part of every childhood trip to my father’s hometown. The second largest earth mound in the United States, Emerald Mound was built by the ancestors of the Natchez people and in use from 1200 through the 1600s CE2. A ceremonial mound stretching out across eight acres, it was built by depositing earth around the base of a natural hill, constructing a mass that would eventually stand sixty feet high with two smaller mounds atop its plateaued summit. The mound served as both the seat of power and the spiritual center for the surrounding villages. In the late 1600s, the Natchez capital was reestablished twelve miles away at the Grand Village, which would function as their center through the early eighteenth century. There, three eight-foot platform mounds and a ceremonial plaza were surrounded by the dwellings of the nation members. The principal chief of the Natchez, the Great Sun lived at the Grand Village, his home stood atop the central mound. The structures on another mound seem varied, built and deconstructed as ceremonial needs dictated. A temple was kept atop the third where a fire burned day and night.

In 1682 after reaching the Gulf of Mexico, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, would claim all the lands and tributaries that drained into the Mississippi River for France. In 1716, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, established Fort Rosalie in present-day Mississippi, which would later be renamed Natchez. The indigenous settlement’s elevated position overlooking the Mississippi River made it prime for the taking by Europeans. The city of Natchez also became a strategic stop along the way to the colonial holding “Nouvelle Orleans,” which was established a couple years later at the mouth. In 1729 and again in 1731, the Natchez and Bambara nations would unite in revolt against the French. In the years that followed, plantations in Mississippi periodically went up in flames. Forks of the Road lies just at the end of the Natchez Trace—a historic trail—at the Grand Village’s edges, just outside of city limits. By the 1820s, New Orleans held the largest market of enslaved people in the country; the second largest was located in Natchez. In 1832, city officials sought to consolidate its human trafficking activities and distance it from the rest of the town. This led them to the Forks of the Road location, which was easy to isolate and police if needed, as it sat amid the planter elite’s part of town.

There is nothing much to say when you are there. All you can do is be quiet and take in the weight—the expanse—of it all.

In 2019, I gave a series of weekly talks at the New Orleans Museum of Art exploring the relationship between New Orleans and Iraq as post-conflict zones and centers of ancient esoteric knowledge in their respective regions. The talks were hosted in conjunction with the 2019 exhibition Bodies of Knowledge and its featured installation 168:01 by Iraqi artist Wafaa Bilal. 168:01 consists of a large bookshelf filled with blank, white books and symbolizes the burning and looting of libraries in Baghdad during the United States’s 2003 invasion of Iraq. The work’s title references the thirteenth-century burning of libraries in Baghdad, when the invading Mongol army threw the books of the Bait al-Hikma—the House of Wisdom—into the Tigris River. According to the legend, their pages bled ink for seven days, or 168 hours. Bilal’s title, 168:01, refers to the first minute after such a loss, which is also, for him, the starting point for recovery. Natchez, New Orleans, and Basra, Iraq, share a unique relationship within the larger narrative of the trade in human life and its global reverberations. The last two stops on the river, where fates were met and destinies determined. Two port cities whose stories about the consequences of war are threads still unraveling. Serious consideration of the cultural rupture of Hurricane Katrina and the permanent displacement of a hundred thousand of New Orleans’s Black citizens as acts of war may be just the beginning, nearly twenty years later, of a process of reexamination.

The archive of war can be a hydra. Cut the head of one untruth in an attempt to assert your own and two more may sprout.

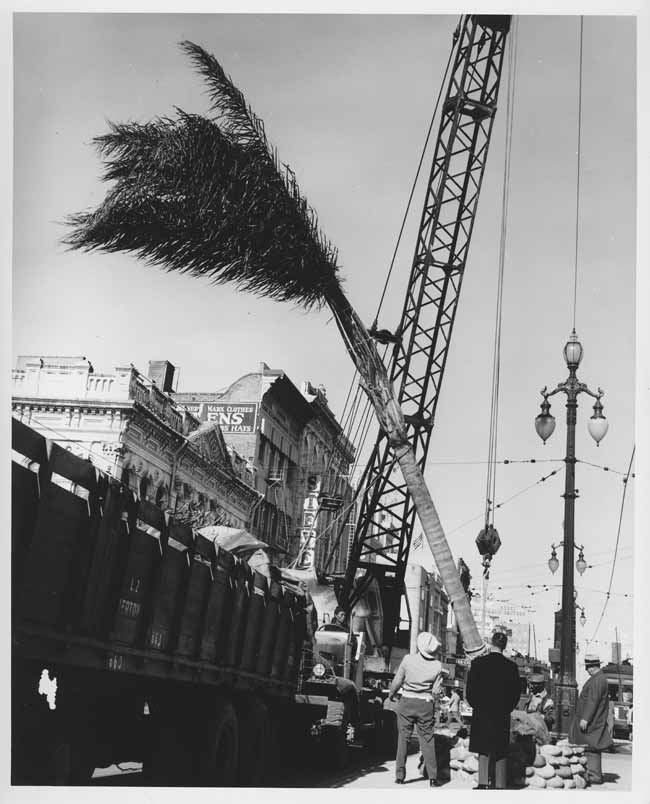

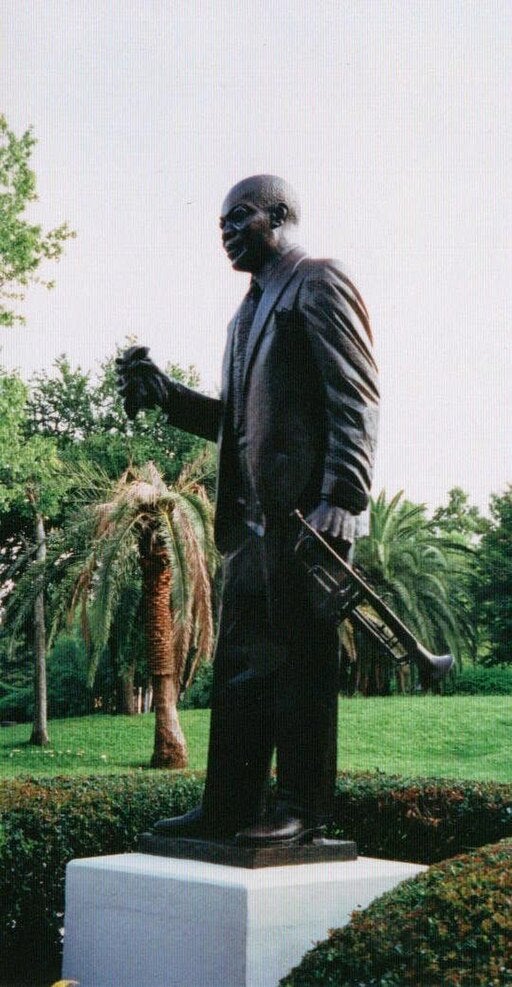

Refusing to acknowledge myself as myself to a stranger that morning on the way to Opelousas has lingered. It had not been a premeditated act. My appearance on the California African American Museum’s social media was made in association with the discussion of Helen Cammock’s I Will Keep My Soul (2023), an artist book and film featured in the eponymous exhibition at the museum and at Art & Practice in Los Angeles and presented as a project of the Rivers Institute in New Orleans. The exhibition includes a film, which opens with my voice, reading from “Our Lady, Prodigy of Miracles,” the short story I contributed to the publication. I appear at other times on camera. I have not at present seen the full film, but recently read a review by AX Mina in Hyperallergic: “The film is nominally centered on the story of the late artist Elizabeth Catlett’s struggles to establish the Louis Armstrong sculpture in Armstrong Park in New Orleans in 1976. That said, Cammock achieves this depiction through interviews with unnamed subjects, who wax poetic on different aspects of life in New Orleans. Without context, viewers see the city through the lens of the speakers’ stories rather than their specific titles, accomplishments, and histories.”

The archive of war can be a hydra. Cut the head of one untruth in an attempt to assert your own and two more may sprout. I’ve questioned since reading the quoted article: Why it is more valuable, comfortable, or “true” to take information from “anonymous,” historyless Black subjects? Whose freedom is at stake when context and being are rendered separate; one given primacy over the other? I’ve been preoccupied with Vulcan, Antoine, and Fanchon, too, who undoubtedly bore different identities before arriving in the Americas, who perhaps resumed those identities in Cuba, or maybe even created entirely new ones as fugitives—living parallel alongside their previously free and enslaved selves. The trio present to me another perspective— some slippage in the desires to claim and prescribe the boundaries of their lives.

memory #2

“Did anyone grow up being told ghost stories?” one of my colleagues asked the group as we jotted down notes from our documents from Keywords for Black Louisiana.

“I did,” I answered. “I got told a lot about the French Quarter.”

“Oh, I mean Black stories. Not those stories,” she replied.

“I mean the quarter wasn’t always like that, remember? Black people lived there,” I said.

Palms are an ever-present motif in the mythos and reality of daily life in New Orleans and the date palm’s relative, the palmetto, with its hardy leaves are ubiquitous throughout the landscape. New Orleans is a city heavily syncretized with Catholic and West and Central African belief systems, including Islam and the Indigenous cosmologies of the land’s original inhabitants, and palms and palmettos play key roles in its ceremonies, masses, and processionals. In my childhood years, the days we attended mass at the St. Louis Cathedral were special. A kind of silent visitation with the previous beings in our familial lineage. I was never afraid of what I felt in Père Antoine’s Alley. Born in the province of Malaga, Antonio de Sedella, more well known as Père Antoine, arrived to New Orleans from Spain in 1774 as an official of the Spanish Inquisition. Despite his official title, the Capuchin friar held a reputation as a minister to the condemned and enslaved. He both baptized and officiated the marriage of Marie Laveau and ministered to yellow fever patients alongside her.

In 1791 and 1795 in Opelousas, two conspiracies led by the enslaved people at Point Coupee to revolt and burn plantations would be uncovered. There

are many stories that have been told in New Orleans for centuries by both those hawking dollars from tourists and those whose families have lived in it since and before its inception. Yet, New Orleans keeps its secrets—still. Some are so sacred they are never told, only held in the fire of hearts—in the latent memories of a culture. Some say you may see Père Antoine and Marie Laveau in the pews of the St. Louis Cathedral, or walking the alley in the cool fog that comes off the river once summer has ended. You may hear about Père Antoine’s refusal to ring the cathedral’s bells, where he was a pastor, because of a prohibition about doing so on Good Friday, leading in part to the spread of the Great New Orleans Fire of 1788, which destroyed the French Quarter and much of the original structure. The new church was completed in 1794 and Père Antoine resumed his position as priest the following year. Outside the small cabin where he lived behind the cathedral, a date palm grew.

[1] Barton, George A, “The Origins of Civilization in Africa and Mesopotamia, Their Relative Antiquity and Interplay,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol 68, N.4.

[2] U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Emerald Mound. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/natr/learn/historyculture/emeraldmound.htm.