In 2018 and 2019, when she scuttled up monuments in public parks throughout Illinois, wrapping them in photographs—or, rather, in an algorithmic composite of photographs—Kelly Kristin Jones was pregnant with her daughter. Subverting the passive, immobilized stereotype of an expectant mother, she climbed and cloaked giant statues in public spaces her future daughter might inhabit alongside other children and neighbors. Jones has always been interested in the role photography plays in constructing our idea of being in and from and of a place, as well as how, in our belonging to and claiming place, we are performing an aspirational idea of what that place represents, what it treasures, what it celebrates. I like to imagine that, as she sought to erase problematic monuments in the Midwest and South, being pregnant made her especially attuned to matrilineal inherited history. It was daughters, after all, who initiated the practice of commemorating a white-washed pro-Confederacy version of history in the South.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) was founded in 1894 in Nashville, Tennessee, with the purpose of commemorating and funding monuments to confederate soldiers. Formed in the post-Reconstruction South, the UDC focused its efforts on preserving confederate lore, guiding the narrative of the Civil War in textbooks, and erecting markers and monuments throughout the region. Generations of white UDC women engineered a landscape dotted with monuments to people who fought vehemently in favor of preserving slavery and who inspired generations of continued racial violence in the South. The job of remembering is women’s work, and often the job of teaching, of telling stories, becomes their work too. What, then, of the work of forgetting?

Functioning primarily as advertisement or souvenir, photography’s role in the creation of art is proportionally small, though the dual citizenship it enjoys as both documentation and artifice makes it the perfect medium to hold truth and lie at the same time. Many of the physical actions Jones performs on monuments and historical markers could be aptly described using the language of photo editing: dodging, spot-healing, blending, and layering. But the tools she uses to fix sculptures’ “imperfections” are not blended or hidden; they are presented in plain sight as fundamental parts of the artistic process. Techniques that would usually be applied on a computer screen are enlarged into gargantuan, Claes Oldenburg-like armatures and coverings that are not wholly convincing and, at times, even slapstick in their appearance. They recall the revisionist landscape photographs of Ana Mendieta and Xaviera Simmons while also speaking to the bleak, typographical built-environments in the works of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Although Jones’s works come out of the crisis of what to do with monuments and spaces claimed by white supremacists, they also address the unspoken slipperiness of thinking of images and landscapes as fixed, static entities at all. This mutability is critical in a time when black-and-white ideas about the world and our orientation to it are being rapidly disrupted by a changing environmental and political climate. Approaching photographs and monuments with earnest dynamism is the only way to accept that meanings and memories are ever-changing mash-ups and remixes of collective—if conflicting—memories.

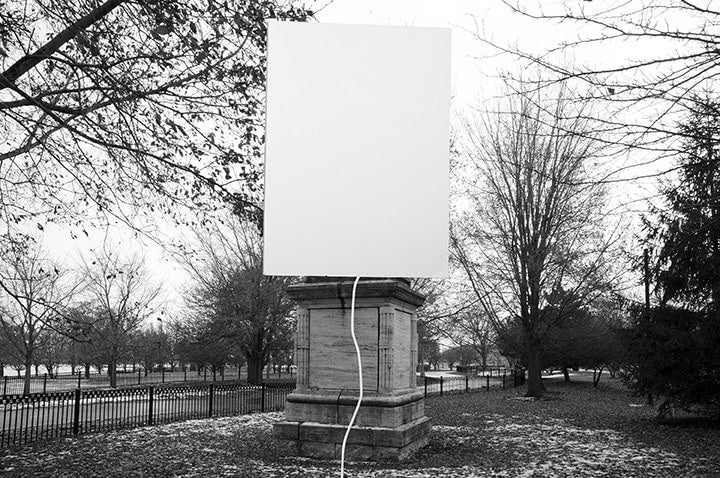

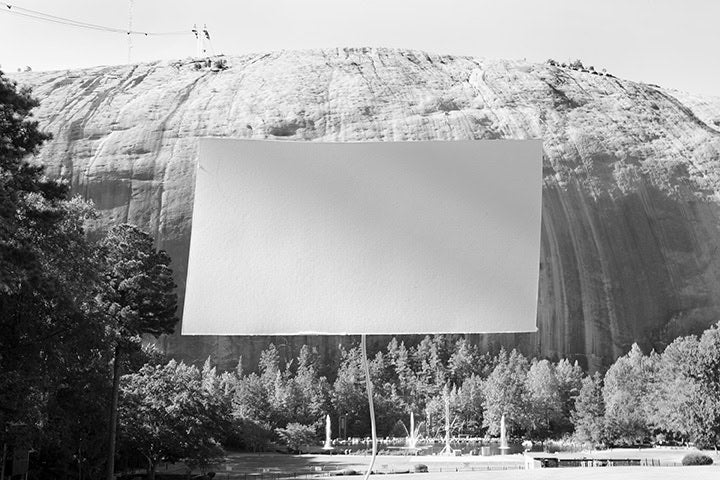

It is the raw potential of landscapes, monuments, and photographs to change, to be “healed,” that drives Jones’s bodies of work. In her “Coverings” series, Jones uses images of the landscape surrounding a monument to make an approximated camouflage covering that is then printed and physically wrapped around that monument. The resulting forms are still quite visible; they read as aspiring to disappear, like a child hiding under a blanket and claiming that they are now invisible. This performative action comes out of earlier bodies of work wherein Jones used the appropriately named “healing brush” in Photoshop to erase monuments and markers from her landscape photographs, the results being glitchy ghosts occupying otherwise bucolic scenes. In the same way that the “healing brush” has limited potential to fix a JPG, Jones’s engineered photographic skins can only do so much to “heal” landscapes occupied by unfortunate monumental blemishes. But the failure to perfectly erase these monuments is exactly the point. Repairing historical narratives will never be accomplished by the swift action of a single artist; it requires the political will of entire neighborhoods, cities, state governments. And yet, Jones’s works propose a strange sort of maternal care: tucking the monument into sleep, into oblivion, into its deathbed under a blanket of printed pixels.

Employing a similar play on the language of the darkroom, Jones’s “Dodging Tools” series brings the corrective magic of physical props to bear on the landscape. Darkroom dodging tools—typically made from wires and scraps of cardboard and paper—are used to shade a portion of a print from the light of the film enlarger. The result is a glowing, lighter region on the print that hides a portion of the photographed subject. Although one can purchase a standardized dodging tool, most are made by the photographer to suit the specific shape and scale of her print. Many are idiosyncratic little shapes quickly fashioned from any spare parts lying around a studio, such as paper clips, masking tape, or scrap paper. In her series, Jones positions these devices directly in front of the camera lens, allowing them to become actors in and subjects of the photograph rather than a hidden production tool.

Jones’s works propose a strange sort of maternal care: tucking the monument into sleep, into oblivion, into its deathbed under a blanket of printed pixels.

These two distinct approaches come together in Jones’s installation Heads of State, in which the silhouettes of statues’ heads are filled with ambient landscape and arranged at varying heights on tripods throughout the gallery. They are the most elaborate dodging tools I’ve ever seen, exactly the shape of the busts they are designed to block. They provide a sense of the scale and physicality involved in Jones’s process. As she leaves most of the photographic wrappings and armatures in situ on the statues after making her documentation, these silhouettes preserve and present the residue of her process alongside the finished photographs.

Directly confronting the sticky mess of inherited history, the Poems for My Mothers body of work complicates the images of men preserved in bronze busts by physically adhering a mishmash of women’s faces to them. It’s more methodical work than wrapping a statue and leaving it to blend (or not) into its surroundings; Jones engineers deliberate, confrontational composites of facial features from found images of women in history books, family albums, and other archives. Some noses, eyes, ears, and lips belong to women with names and preserved histories, while others are anonymous. The resulting face betrays the calm austerity of the original bronze bust and presents something that is grotesque and multi-faceted, revising and challenging the idea of the solitary hero. What would it look like to honor the quiet contributions of many people at once instead of picking an individual representative of a moment or a movement?

Throughout her recent projects, Jones is asking us to see and unlearn what has been hiding in plain sight in our parks, our streets, our neighborhoods for generations, and to imagine what would better represent the American story—what else might honor the pain of nation-craft with as much honesty as we honor its idealized valor? In a moment when plans to put the image of a woman on an American bank note for the first time have been back-burnered by an unabashedly misogynistic administration, and medals of freedom are doled out to the most vocal proponents of misinformation and blatant racism, Jones asks us to look at how the people and stories we have honored and preserved in the past are misremembered today. This act, in turn, asks us what sort of real and implicit monuments we are building into today’s world—will they be as baked with lies and idealizations tomorrow? She understands that white supremacy and misogyny are not the ghosts of nineteenth-century America but still live in the American psyche, limiting any possibility of reconciliation until they are blotted out in the landscape and in our structural understanding of the world around us.

The solo exhibition Kelly Kristin Jones: The End of History is on view at the McEachern Art Center at Mercer University (332 2nd Street) in Macon, Georgia, through April 3. This essay will appear in a forthcoming catalogue accompanying the exhibition.