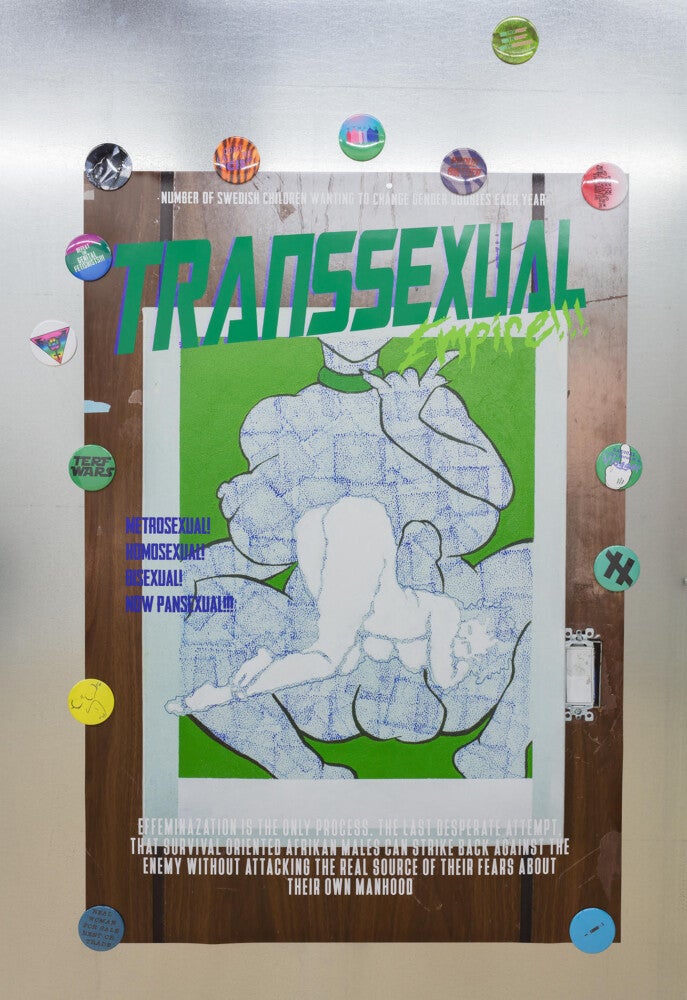

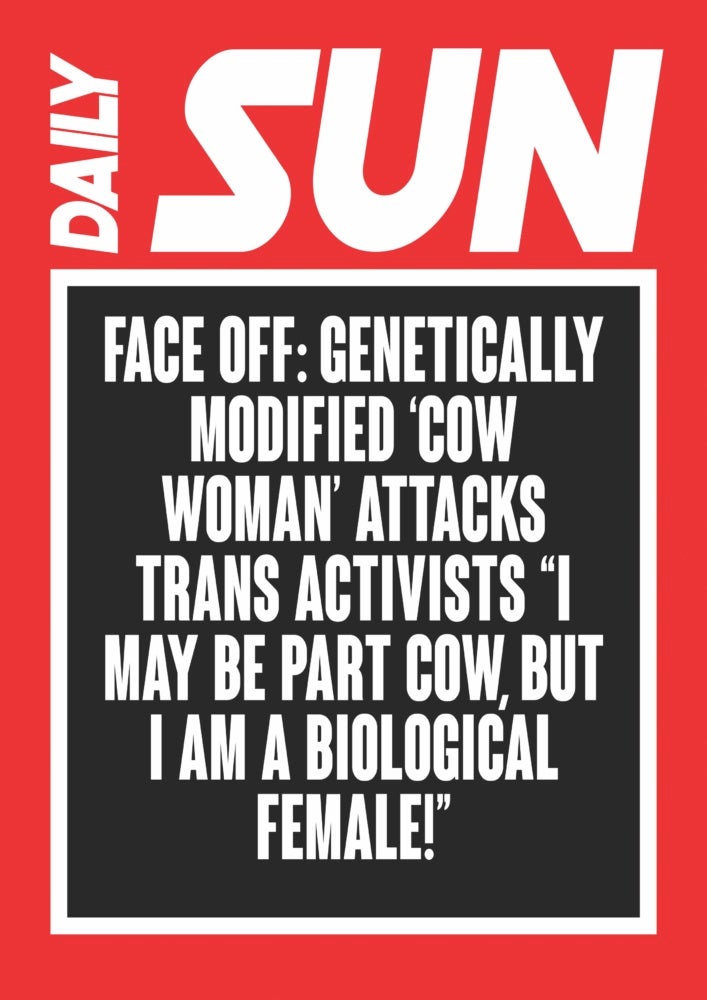

“POST PUNK! POST CLOTHES! HARD CORPOREALITY” reads a stylized Bulletin dated “Wedmesday Marc 26 2045.” The false headline is from Juliana Huxtable’s 2019 show at Reena Spaulings Fine Art in New York City. The poster serves as a mission statement for the Bryan-College Station, TX, born artist’s extensive output, including but not limited to photography, poetry, music, and DJing. The show, titled INFERTILITY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX: SNATCH THE CALF BACK, wasn’t an introduction to Huxtable’s work, instead, a deepening of existing motifs with a new emphasis on photography. Next to the bulletin is a self portrait of the artist as a defecating cow, Cow 1 (2019). Photographed from behind, she looks over her shoulder with a dissonant expression, neither shocked nor repulsed. Body paints are applied in a pink and purple cow print, as well as an additional top layer of paint rendering her lower half as fully bovine.

Despite applying apparent layers of both paint and digital illustration, Huxtable’s work exists as a single flat surface, vacuum sealed composites of humans with other animals. In the repeated action of flattening, she critiques shallow renderings in fashion and larger media tropes with the same glossy veneer often reserved for magazine spreads; rather than negate visibility altogether, Huxtable uses the tools of the media in which she participates, reveling in the erotics (and fun) of self-portraiture. The flattening is realized through camouflaged patterns, perverse symbols, and mediums of digital reproduction. She’s not using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house, to use Audre Lorde’s more succinct metaphor, instead building her own, freakier house.

Beginning with the tools of studio photography, tools which emphasize the flat image, Huxtable imagines herself as animal and humanoid avatars via body paints and other prosthetics. She then prints the pictures on canvas and applies further details in layered paint, a process that recalls early animation cels. The bestial works are a direct but strange response to the conservative speculation that people using gender affirming hormones will eventually go so far to transition into animals.1 In another work, HISS PLAY (2022), Huxtable is a towering serpentine figure with a human bust, wearing both tiger stripes and cheetah spots; a new species to meet the moment. Through visualizing this irrational thought experiment as photographs, Huxtable embodies something stranger, more corporeal.

Huxtable’s patterns act as a camouflage for the wearer, by definition a flattened approximation of nature; it is easily reproducible and adorns military garb, trendy garments, or faux animal pelts. In Cruising Utopia (2009), José Esteban Muñoz addresses Warhol’s camouflage self portraits, wherein camouflage’s utility in mimicking nature is instead used to point to the instability of what is natural, or “call[ing] the natural into question.”2 To augment these patterns in neon Huxtable draws attention to both the wearer and the changing landscape in which they exist, even in human-made conditions. An example in nature can be found in the evolution of the peppered moth during the industrial revolution, a Darwinian vignette in which darker variations of the moth became more common as their color made them blend into newly soot-covered trees. Nature is able to respond to the manmade, making the dichotomy more an ambiguous exchange than rote cause and effect.

She’s not using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house, to use Audre Lorde’s more succinct metaphor, instead building her own, freakier house.

To question of the supposedly natural feels especially potent when regarding coverage of Huxtable’s early career, as it paralleled new cultural conversations about LGBTQ+ Americans, from same-sex marriage to new gender identity options on government identification. She is rightfully skeptical of these milestones, giving the example of H&M’s 2019 pride campaign featuring transgender actress Laverne Cox: “[…] If Laverne Cox in a H&M campaign implies ‘that’s a win for all trans people,’ it is assumed visibility is the same as the shifting of political, economic and cultural resources.”3 Huxtable’s work in part parodies these conversations, as she created falsified ephemera mimicking the intersection of activist slogans and corporate speech.

Huxtable’s profile rose after participating in the 2015 New Museum Triennial: Surround Audience. Vogue would call her the “star” of the show.4 Though the exhibition wasn’t her debut, having already been a known figure in New York City’s underground, it did bring her a new, substantial media coverage. Her work in that show included two self portraits riffing on Nuwaubianism, an American new religion with headquarters in Putnam County, Georgia. The religion began as a branch of Islam, but would grow to include a wide array of motifs, most notably those of Ancient Egypt. She would describe these references as a way she could “code images.” “[…] I tried to think how I could create images that abstracted a political impulse into symbols—but symbols that still retained clear political associations.”5 She gives the example of the black panther, the symbol appearing in artworks in her childhood home even though her family didn’t necessarily agree with the radical politics of the Black Panther Party with which the animal is often associated.

Demonstrated by Huxtable’s reference, the flattening, the lessening of associations and other meanings within a symbol, of the black panther into a universal pro-Black symbol allowed it to seep into households that may not adopt the entire message with which it originated. It is equal parts a defanged assimilation and a smuggling of symbols through banal borders like the domestic sphere. The modern equivalent may be her works proliferation on the internet, her artworks increasingly viewed as jpegs on websites like Contemporary Art Daily and fashion magazine Dazed and Confused. Part of the growth and subsequent success of the work is that it is a digitally flat artifact, easily reproducible images that lose nothing in their flattening.

It feels like a giddy secret, then, that Huxtable uses her platform and her work to embrace something so messy and liquid within a clean, slick format. The medium acts not as a seductive lure for unsuspecting viewers, but as necessary and embedded; form is not a means to an end but the thing itself. The flattening of viscera, “LIKE SNOT, MUCUS, CUM, SHIT SWEAT – THE UNITING ELEMENTS THAT FORM THE BASIS OF REALITY,” to quote one of her poems, into polished images may be her greatest trick.6 It’s a worthy paradox, beings with the indexes of reality (SNOT, MUCUS, etc.) trapped in fictitious flat surfaces, somewhere between the supposedly real and fake. It’s funny even, to render these actions within the languages of both fashion and fine art, yet beyond the implied shock is a real claim to bodily autonomy and freedom. The hyperbolic characters act as greater conduits for the material elements of reality.

Huxtable proves that flattening and imaging can exist without the compromise of complexity or dignity. Transgender people have been required to flatten themselves into an increasingly rigid gender binary due to a hostile wall of legislation in North America.7 In her own thought experiment, she asks: What does it look like to disregard those oppressive forces and share the result? Huxtable’s applications of twisted symbols and patterns, her smearing of viscous substance on fashion magazines, builds a flat surface on her own terms, one that is both, rather than neither, a photograph and a painting, or a cow and a human. The complexity lies not under or around, but within the flatness of the work.

[1] “Or, if you let men identify as women, or women identify as men, then you might as well let anyone identify as an animal, as a dolphin or a tarantula. So, I asked myself, what is at work in the anxiety surrounding that?” Bella Spratley, “Juliana Huxtable – Play With Truth.” Metal Magazine, 2020, https://metalmagazine.eu/en/post/juliana-huxtable.

[2] José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity: (New York, New York: New York University Press, 2009), p.138.

[3] Spratley, “Juliana Huxtable – Play With Truth.”

[4] Mark Guiducci, “Meet Juliana Huxtable: Star of the New Museum Triennial,” Vogue, February 27, 2015, https://www.vogue.com/article/juliana-huxtable-new-museum-triennial.

[5] Juliana Huxtable and Che Gossett, Existing In the World: Blackness at the Edge of Trans Visibility, in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, Critical Anthologies in Art and Culture, ed. Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2017), 39–55.

[6] Juliana Huxtable, Mucus In My Pineal Gland (New York City, New York: Capricious & Wonder, 2017), p.7.

[7] “2024 Anti-Trans Bills Tracker” Trans Legislation Tracker. Accessed on September 26, 2024. https://translegislation.com/

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Crush.