“I had no idea that was up there! I thought it was a normal historic house!” says artist Joni Mabe, imitating common reactions to the museums located on her property in Cornelia, Georgia, approximately an hour and a half northeast of Atlanta. The incredulity being parroted by Mabe—who is often called the “Elvis Babe” or “Queen of the King”—is understandable given the unassuming appearance of the early twentieth-century, two-story structure sporting a National Register of Historic Places plaque in its front yard. The prominently displayed plaque describes the lives of Robert Lee Loudermilk and his wife, Phanettia Callie Henderson Loudermilk, and the building’s importance to local residents, travelling salesmen, WPA workers, railroad employees, farmers, and other laborers. At second glance, one detail of this historical marker seems unusual: among the list of sponsors including the City of Cornelia and the Habersham County Historical Society, Georgia rock band R.E.M. is listed first. Why should a rock band take interest in an historic house?

“I had no idea that was up there! I thought it was a normal historic house!” says artist Joni Mabe, imitating common reactions to the museums located on her property in Cornelia, Georgia, approximately an hour and a half northeast of Atlanta. The incredulity being parroted by Mabe—who is often called the “Elvis Babe” or “Queen of the King”—is understandable given the unassuming appearance of the early twentieth-century, two-story structure sporting a National Register of Historic Places plaque in its front yard. The prominently displayed plaque describes the lives of Robert Lee Loudermilk and his wife, Phanettia Callie Henderson Loudermilk, and the building’s importance to local residents, travelling salesmen, WPA workers, railroad employees, farmers, and other laborers. At second glance, one detail of this historical marker seems unusual: among the list of sponsors including the City of Cornelia and the Habersham County Historical Society, Georgia rock band R.E.M. is listed first. Why should a rock band take interest in an historic house?

As you approach the front porch, you might notice a second plaque reaffirming the building’s historic status. In the corner to the right, something looks out of place: the bust of a white male figure with dark, wavy hair, a piece of which droops downward in the front.

After paying ten dollars for admission, you’re guided by Mabe to the back of the house’s entryway and into a room on the right. The room is filled to capacity, containing a bed, dressers, jewelry, dresses hanging on the walls, hundreds of buttons, government-issued bags, hats, photographs, chairs, decorative pieces, a sewing machine, a chest, a stove, and a crib—all dating back to the first half of the twentieth century. Mabe explains that her family has owned the house for four generations and that her great grandparents and grandparents ran it as a boarding house between 1920 and 1980. A rope separates the room and objects from the viewer, and small cards read “Do Not Touch” in English and Japanese. The room exudes a kind of reverence for the lives of Mabe’s relatives. When asked why she starts the tour with this history, she explains, “It’s sort of the history of me. It’s a personal touch to tell about the house—why this house… It would all be lost if I didn’t share it.”

As a graduate student at the University of Georgia in Athens during the early 1980s, Mabe spent much of her time in the printmaking studio. One day, she crossed paths with a handsome undergraduate who was in the studio working on a project for his lithography class. She told him his lips looked like Elvis’s.

After his death in 1977, the Mississippi-born American singer Elvis Presley had become a quasi-religious figure for Mabe. She began making artwork inspired by the singer, which she then traded for rare Elvis-themed memorabilia and purported relics he had allegedly left behind. Eventually, her final graduate project was comprised of such Elvis-related artworks, which often employed appropriated images, glitter, and sequins to create mosaics reminiscent of religious icons. “It was sort of a scandal!” Mabe says now. “Nobody had ever done their master’s on Elvis.” In 1984, her work was included in a group exhibition at Nexus Contemporary (now known as Atlanta Contemporary) called I Wanted to Have Elvis’s Baby But Jesus Said It Was a Sin.

During the late 1980s, Mabe journeyed across the United States showing her Traveling Museum of Obsessions, Personalities, and Oddities, a zany, kaleidoscopic sideshow that grew out of her fascination with Elvis. In November 1992, upon returning to Georgia from Los Angeles, she discovered her mother had sold the family boarding house to the people operating the hardware store located next door. Horrified, she immediately began trying to purchase the dilapidated house back from its new owners. After finally settling on a price of $22,500, Mabe moved back into the house in January 1993. “I ordered the National Historic Places plaque way ahead of restoration,” Mabe says. “I was determined. I worked like a dog.”

The same month Mabe returned to Georgia, her old friend Michael Stipe—the boy whose lips she had said looked like Elvis’s—released the video for the song “Man on the Moon” with his band R.E.M., which had transitioned from college radio airwaves to the top of international charts following the release of their seventh album, Out of Time, the previous year. In the video for “Man on the Moon,” Stipe lowers his hips and gyrates in an imitation of Mabe’s patron secular saint, crooning, “Hey, Andy, are you goofing on Elvis?” Stipe and the other members of R.E.M.—Bill Berry, Peter Buck, and Mike Mills, who had also known Mabe in her Athens days—helped pay for the iron marker identifying the Loudermilk Boarding House as a historic site.

It took Mabe nearly seven years to restore the property, and she re-opened the house to visitors in 1999. “I installed it on the idea that when you build it, they will come,” Mabe says. Her travelling show, once called the Panoramic Encyclopedia of Everything Elvis, is now permanently on view as the Everything Elvis Museum, just a staircase away from the historic boarding house museum below. “Maybe people will come here instead of me travelling all over the place,” Mabe says.

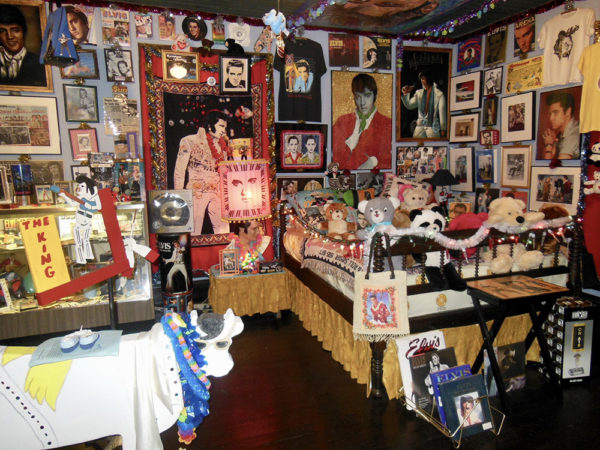

The Everything Elvis Museum occupies every inch of the second story of the 1908 building, enveloping you in an immersive cabinet of curiosities devoted to Elvis culture, fandom, and Mabe’s own Elvis-inspired art. From downstairs, you see that something colorful and bright awaits: the staircase is lined with photos of Elvis, teddy bears, license plates, knickknacks, and at the top, a glittery artwork showing the King himself. Like Mabe’s work, the collection incorporates artistic prints, tinsel, lace, fake flowers, newspaper clippings with headlines such as “Picture of Elvis Cured My Cancer,” old photographs, candles, and every imaginable object emblazoned with Elvis’s image, including an apron, a blow-up doll, a flip book, mittens, and dresses made by Mabe.

Comprising just four rooms and a hallway, the collection takes an intensely physical yet spiritual form. You’re asked to believe that you’re seeing the actual wart from Elvis’s hand, a vile of his sweat, a few strands of his hair, dirt from his grave, and a shirt he once loaned someone. There is something visceral—even freakish—about the kind of Elvis worship depicted in Mabe’s Everything Elvis Museum. In Erika Doss’s 1999 book, Elvis Culture: Fans, Faith, & Image, she writes:

…a veritable Elvis religion has emerged, replete with prophets (Elvis impersonators), sacred texts (Elvis records), disciples (Elvis fans), relics (the scarves, Cadillacs, and diamond rings that Elvis lavished on fans and friends), pilgrimages (to Tupelo and Graceland), shrines (his Graceland grave site), churches (such as the 24-Hour Church of Elvis in Portland, Oregon) and all the appearances of a resurrection (with reported Elvis sightings at, among other places a Burger King in Kalamazoo, Michigan).

While the belongings of Mabe’s family members are held at a reverent distance downstairs, with a rope preventing you from getting too close, your interaction with the Elvis paraphernalia upstairs is an unsupervised, immediate experience, with nothing separating you from what’s on view. Beyond the visual and tactile elements of the collection, songs by Elvis play in the background of every room. The experience is comparable to that of a pilgrimage to a Catholic cathedral, although one adorned with kitschy relics from pop culture.

“With Jesus there’s a guilt we carry because he had to die for our sins, and with Elvis we made him a prisoner of his fame,” Mabe argues. “We killed him, you know? He was religious himself, yet he was a sex symbol. He combined the two long before Madonna did in the 80s. He was a contradiction. When you talk about religion, sooner or later, you’ll talk about sex, so he combined those two.”

Throughout the museum, images of the confederate flag are mixed in with those of Elvis and other public figures. One image in the stairwell depicts Elvis in front of a glitter mosaic of the confederate flag. Elsewhere, Elvis stands before the flag with his belt, which usually proclaims his trademark slogan “TCB,” or “Taking Care of Business,” but is here replaced with “CSA,” or Confederate States of America.

For Mabe, who did significant research on her family history while restoring the Loudermilk Boarding House, her ancestors’ confederate background is simply a matter of fact. When asked about her relationship with the contentious symbol, Mabe replies, “I’m Southern, and Elvis is Southern. I didn’t choose who my ancestors were.” She follows this statement with a story about one of her confederate family members who was captured by the Union Army and switched sides as a result. He didn’t tell his Southern family about what had happened after the war, but according to Mabe, “He kind of redeemed himself.” As with Elvis’s pious yet sensual nature, Mabe is comfortable in this kind of duality and contradiction.

Indeed, the two museums—The Loudermilk Boarding House Museum and the Everything Elvis Museum—are all the more fascinating because of the way they contradict each other. Mabe’s juxtaposition of a historic boarding house and a pop culture fun house achieves her stated goal: “I’d like for [visitors] to go in and appreciate the building as historic and an antique, and then to get a kick out of the Elvis museum having nothing to do with the historic building. Sort of two opposites,” she laughs. The contrast between the two is jolting, yet as creations of the same artist, both collections have a similar effect in their presentation: the contents of each occupy as much of the available space as possible and possess a sort of kinetic energy in their arrangement as mosaics of cultural and personal memory.

But Mabe’s obsessions extend beyond her historic property, or at least as far as the road in front of it. In addition to Elvis, it turns out that roadkill is among Mabe’s primary artistic inspirations. “The idea of flattening something completely fascinates me,” she says. In order to create certain artworks, she has done just that: flattened objects such as aluminum cans, a tricycle, and a shopping cart by running them over with her car, often directly in front of the Loudermilk Boarding House. Using these components, Mabe creates sculptural assemblages that appear both nostalgic for and critical of romantic notions of Americana.

Four of these assemblages and two of Mabe’s glitter mosaics are included in the 2019 Atlanta Biennial, A thousand tomorrows, co-curated by Institute 193 founding director Phillip March Jones and Atlanta Contemporary curator Daniel Fuller.During a curators’ tour that took place two days after the biennial’s opening, Jones compared Mabe’s assemblages to those made by self-taught artists Lonnie Holley and Joe Minter, who have also recently shown their work at the museum. In doing so, however, he identified a key difference between those artists’ work and Mabe’s: where Holley and Minter imbue castoff items with new significance, Mabe’s assemblages seem to question the preexisting associations with the flattened objects that comprise them. Instead of creating new meaning, her artworks invoke and playfully deconstruct elements of pop culture whose meaning seems resolved and stagnant, or, in other words, flat.

[su_spacer]

After all, what could be more flat, culturally speaking, than Elvis? Even at the time of his death, when Mabe first became fixated on him, Elvis was uncool. “Back then, it was like he was Wayne Newton. It wasn’t hip to be an Elvis fan,” Mabe has said. In dedicating so much of her personal resources and creative energy to preserving and reimagining the singer’s image, the artist has shown that the cultural significance Elvis represents is anything but resolved and, more broadly, that whatever is dismissed as insignificant kitsch actually contains layers of latent meaning.

Regarding the objects she flattens like roadkill, Mabe says, “I usually do rubbings of them when I’m finished, and when I do a rubbing it looks 3-D.” In a certain metaphorical sense, this is also what she has done with the museums she operates out of a century-old boarding house in Cornelia, Georgia: drawn unseen dimensions out of cultural relics that would otherwise be seen as trash on a country road.

Artist Joni Mabe’s work continues to be on view as part of A thousand tomorrows, the 2019 Atlanta Biennial at Atlanta Contemporary, through April 7. The two museums Mabe operates in Cornelia, Georgia—the Loudermilk Boarding House Museum and the Everything Elvis Museum—are open from 10 am through 4 pm on Friday and Saturday, April through November.