Art history is brimming with stories of masterpieces lost to time—nothing lasts forever. This may be because of negligence (Marcel Duchamp’s original 1917 Fountain was misplaced), tragedy (Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1850, was lost in a fire a year after its creation), or acts of war (Courbet’s The Stone Breakers, 1849, was destroyed in the bombing of Dresden). This potent absence adds to the mythology of the work, inviting a sense of reverence. Viewers want to see what is not there. But what happens when an artwork meets an unglamorous end? In 1952 a dull coat of paint abruptly wiped away a mural whose raw, grim, noisy call could be heard from Mexico City. John Wilson’s The Incident did not survive intact, but the memory of the mural is seeping back into public consciousness.

A reproduction of the lost mural is the centerpiece of the traveling exhibition Reckoning with The Incident: John Wilson’s Studies for a Lynching Mural, which was on view last fall at Atlanta’s Clark Atlanta University Art Museum and opens this week at the Yale University Art Gallery. John Woodrow Wilson (1922—2015) was an American artist from Roxbury, Massachusetts, where his parents arrived as immigrants from British Guiana, known today as Guyana. From a young age, he was making and showing art at the Boys Club, where his teachers helped him receive a full scholarship to the Museum of Fine Arts School, Boston. In 1947 the James William Paige Traveling Fellowship facilitated his move to Paris to work in the studio of Fernand Léger. Wilson returned to America three years later and participated in what was the only national exhibition of African American artists that year, the Third Annual Atlanta University Exhibition hosted by Atlanta University, now known Clark Atlanta University. At a moment when Abstract Expressionism maintained its darling status in the mainstream art world, Wilson embraced social realist murals as visual tools for his own activism.

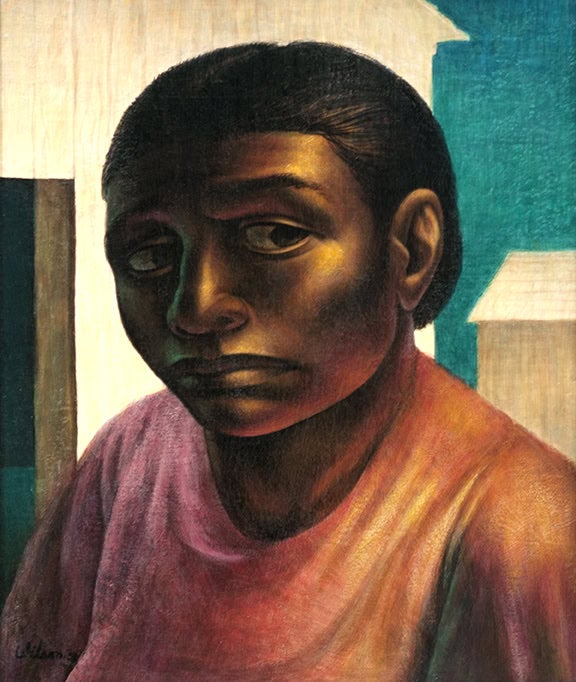

oil on Masonite, 21 1/2 by 18 inches.

Wilson had been aware of racial injustices from a young age. His father was an avid reader of the New York Amsterdam News, a weekly African American newspaper from Harlem, which Wilson claimed contained images of lynchings in “every other issue.” He would later be drawn to the work of the famous Mexican social realist and muralist José Clemente Orozco. Wilson lived in Mexico from 1950 through 1956, attending La Esmeralda, the national school of art in Mexico City. While taking a mural painting course taught by Ignacio (Nacho) Aguirre, Wilson painted The Incident, a street-level fresco that towered over passersby at two times human scale. The work was a masterpiece of mortal terror, showing a Black family watching through a transparent window of their home as Klan members in full regalia cut down the body of a lynched man.

Between 1877 and 1950, there were more than 4,000 murders nationwide of African Americans, and large mobs killed 360. All but four American states saw lynchings. These atrocities, acts of racial terrorism, were never punished. Victims were mostly unacknowledged. In The Incident, Wilson attempts to give them a voice.

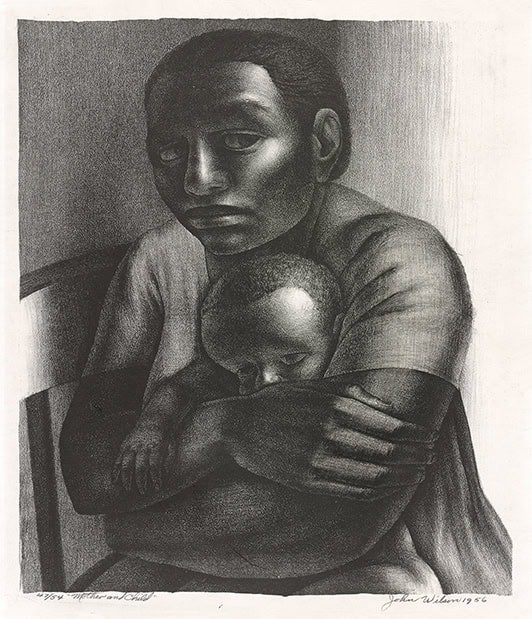

lithograph, 21 3/8 by 17 7/8 inches.

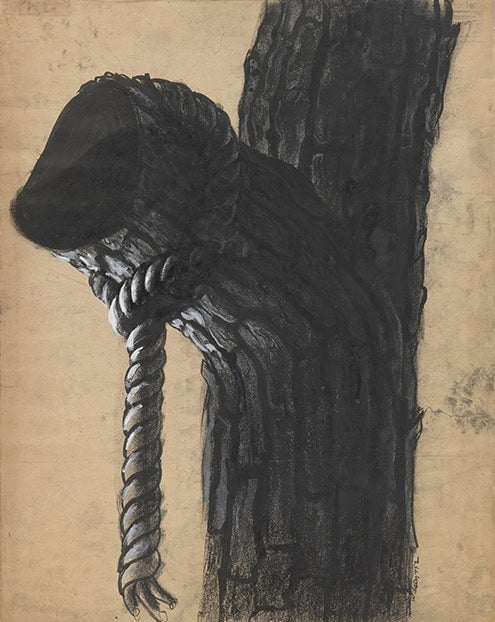

lack crayon, India ink, white watercolor, and charcoal,

23 1/4 by 18 1/2 inches.

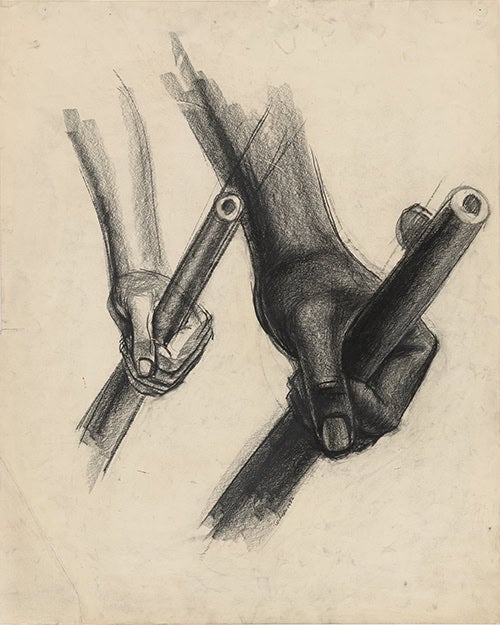

The mural was conceived in two parts. To the left, inside the house, a petrified mother sits in a chair, clutching her child. She sits with her back to the barbarity outside, sagging, as she tries not to look, but her eyes fail her, peering backward. Just a toddler, the baby’s eyes are open wide. Her body appears to inhale the child, squeezing him tight to her stomach, with his arm poking through her embrace. A figure implied to be her husband stands above them, wearing a crisp white shirt under overalls, his left hand grasping the barrel of his shotgun. His hand is substantial, formidable, as is the broad open muzzle of the gun. There is a coolness, a toughness, to his spirit, a beauty to his defense of their dignity. They are not hiding, but terror has come to their doorstep.

The right panel depicts four ghoulish Klansmen cutting down a hanged black man from the stumpy, lifeless tree. A wooden cross is overwhelmed by orange and yellow flames. The deceased man seems enormously tall in comparison to his killers in their pointed hoods. His body is limp, his neck rolled back, facing the heavens. His colossal right-hand lolls on his left knee; the distorted fingers are splayed-out nearly the width of his waist. Below the knee, his left leg has snapped, now gruesomely bent in an unnatural direction, indicating the removal from the tree was not gentle. A ham-fisted Klansman stand over him with a fluid bullwhip spilling to the ground, snaking over itself in asymmetrical loops. It is a captivating detail: the whip knows no justice, and its reach has no end.

Reuniting twenty-three preparatory sketches, the exhibition unveils how compulsively he fixated on every gesture, each aspect of the mural. There are oil paintings, lithographs, and drawings in chalk, crayon, graphite, and gouache. Some of the pictures are fast and fleshy, with weighty crayons and charcoals showing black and white fists tensely gripping their gun barrels side-by-side. In these sketches, the hands float in perpetuity, a highly honed standoff, neither side relenting a smidgen of power. The broadest range appears in the representations of the mother and child. Sometimes the mother’s glassy eyes stare straight ahead; sometimes they feel vacant, on the verge of a break. In two oil paint studies, Wilson illustrates her peeking up. In the light, her worn eyes meet ours, and then she is bathed in a ghostly shadow. She is unable to watch the titular incident, focusing instead on the embrace of her child, trying to remain calm amid the storm. In lithographs on view, the rest of the world fades out of focus. In these drafts, time slows down, and it is just the two of them. These painstaking sketches show Wilson’s passion, his absolute need to create something monumental expressing the reality, and revealing the resilience of all African American families.

Wilson wanted this work to be accessible to everyone, to live beyond the confines of a museum or collection. As history has been compressed, forgotten masterworks of art such as this are frequently omitted from the books. Now sixty-seven years after the erasure of The Incident, the mural’s subject matter is still inescapable. It is past time to revisit Wilson’s work. Bringing these artifacts together marks a long ripple through time, drawing images of the fuller American experience slowly back to shore.

Reckoning with “The Incident”: John Wilson’s Studies for a Lynching Mural opens at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, on January 15. The exhibition was previously on view at the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum from October 6 through December 6, 2019.