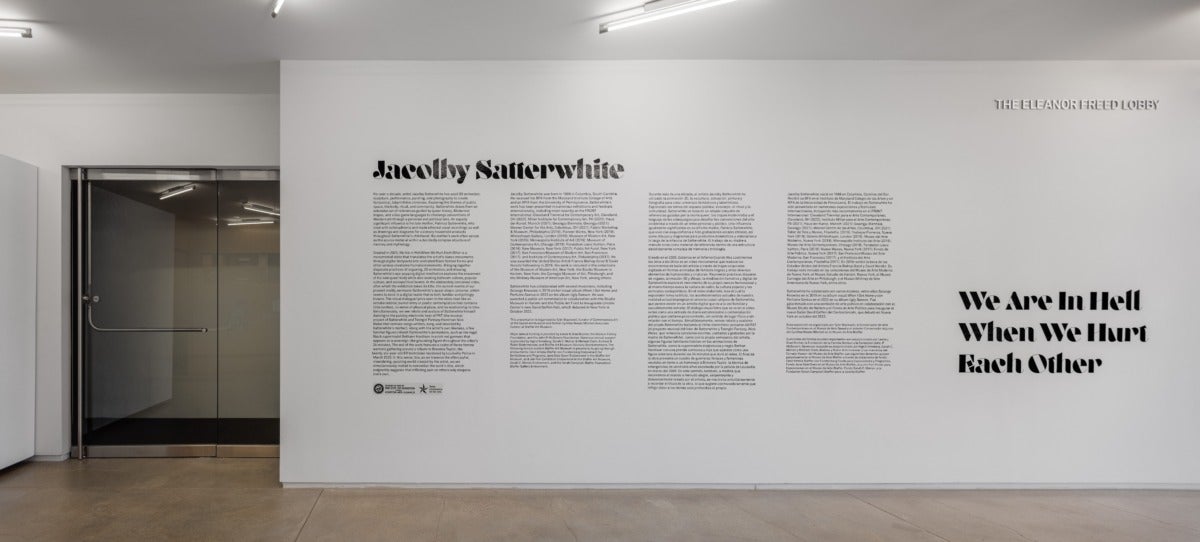

After seeing Jacolby Satterwhite’s We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other (2020), I’ve been stuck on one word: resurrection. The fault is my own. After becoming enamored with the video, currently on view at the Blaffer Art Museum, in Houston, Texas, I started Googling the artist and came across an interview he did for Art21. In the interview, Satterwhite explains playing Final Fantasy as a form of escapism while being hospitalized for cancer treatment as a child. This relationship to technology as a coping mechanism is paired with Satterwhite’s decades-long obsession with the religious iconography of Doubting Thomas in order to come to terms with his own existence. “I’ve been skeptical of my own mortality my whole life,” Satterwhite concludes.

Satterwhite’s response to survival is a roiling virtual Utopian landscape of iridescent lilac stages, candy pink skies, and manicured gardens—an updated Garden of Earthly Delights. Topless femmes spin around in a galaxy of voguing avatars, some of which are live-action footage of Satterwhite himself. It’s a baroque, opulent chaos, the rhythm of which only the residents of this digital galaxy know the logic to. Even its color palette feels like a form of reassurance, a stake in one’s ability to create the idyllic, if only, within one’s own mind. As Patricia Satterwhite, Jacolby Satterwhite’s mother, sings over the virtuosic panorama, the video evokes the idea of a paradise “planting in the air,” spun from the invisible threads of the Internet.

An anomaly in my generation, I can barely work my iPhone. Screens were largely banned from my home so I didn’t play video games, which also means that I didn’t understand their impact. It is only later in life that I learned about the political possibilities of the Internet, such as Climate Fiction (CliFi) augmented reality game Sin Sól, by micha cárdenas or its sinister sister, Lil Miquela, a mixed-race virtual influencer which is as much a tool for cultural vulturism as Sin Sól is a social intervention.

Satterwhite falls somewhere in-between. Having collaborated with icons like Solange and Dev Hynes, he’s no stranger to mass consumption. However, the foundation of his work is still rooted in the deeply personal and the strange. We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other has less of the sly capitalism of Lil Miquela or the academic tenor of Sin Sol. There is an unclassifiable joy to Satterwhite’s avatars, a literal multiplicity as opposed to marketable insularity. Through his digital landscapes, Satterwhite creates a literal new world order in which golden butterflies can fall from the sky, the dead can be revived through animated objects, and digital avatars can be your avengers. As Michael Bullock put it in PIN-UP Magazine, “The artist draws on his technical virtuosity to reclaim the video-game environments of his childhood, re-inhabiting them with his own community all through the sharp lens of art history.”

We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other breathes new life into the emancipatory potential of the Internet by linking it integrally to personal experience, seeing technology as a response to our lives, rather than its natural extension, and looking not at how we all have become cyborgs but why. The most banal writing on the Internet argues that there is no difference between IRL and online. Satterwhite suggests something more than trite manifestos on techno-fusion. Combining the personal, art historical, and the visionary, his works are as much about the past—personaland art historical—as the present or future. Can projects like these resuscitate the Utopian vision of the early Internet? Can they mimic our emotional landscapes as well as our lived ones?

Immersive: a word echoed in almost every review of Satterwhite’s work. Beyond immersive, his digital landscapes orchestrate a call and response between lived and digital experience. In many ways, We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other is a lesson in perspective. The video game isn’t something that separates one from lived reality. It’s a tool that allows one to see it from different vantage points. The real world is merely footage in this surreal universe. On a music festival screen, an industrial cityscape and smoke stacks roll, a far removed scene from the rose-tinted open fields of We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other. Satterwhite’s dancers gyrate unbothered in front of clips from a Jerry Springer fight, not engaged in the show’s aggression, and instead absorbed in their own movements. In the Art21 interview, Satterwhite explains, “I’m a millennial with an addiction to Instagram and my iPhone. I lean into it, use it as material and try to make it tactile and poignant and make it feel like skin.”

There is something deeply moving about this urge to reanimate your loved one, to use technology like a time machine.

Watching We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other (2020) feels like wandering into a memory. The work is scaffolded by Satterwhite’s reverence of his late mother, Patricia Satterwhite, who suffered from schizophrenia and died in 2016. The piece is accompanied by a soundtrack of pop songs, featuring his late mother’s acapella cassette recordings, which Satterwhite developed into a concept album in collaboration with Nick Weiss of Teengirl Fantasy. Throughout her life, Patricia Satterwhite recorded 155 acapella cassette tapes while institutionalized as a way to calm her episodes. She also created a mountain of drawings of possible consumer products that she hoped would one day appear on the Home Shopping Network. In the video, designs for products such as “pizza with Pringles seasoning” are animated and stalk across the screen.

Satterwhite’s work highlights the ability of gaming to map affect. In her essay “The Fantasy of Healing,” Vanessa Angelica Villarreal recalls using the game The Witcher to process her divorce. “Already these weren’t just characters,” Villarreal notes, “they were two people with a history.” Later on in the piece, Villarreal cites studies that show video gaming as a more effective PTSD intervention than talk therapy.

The video’s sensory quality is amplified by the matriarchal power of Patricia Satterwhite’s ethereal mantras. A section of We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other features steely fembots who whip their long braids to shatter looming monsters into pieces. “I will never go back to the way I used to be,” Satterwhite sings, as the fembots calibrate their hips to avoid, and then destroy, descending disco balls. One can’t help but read the scene as corrective, as a way to go back in time and amend the past. There is something deeply moving about this urge to reanimate your loved one, to use technology like a time machine.

In a conversation for VICE with Solange, Satterwhite credits his elemental sensibility to where he grew up:

“I’m from Columbia, South Carolina, which is country. It is magical. I grew up in the church, and with a lot of Holy Ghost carrying. It was a specific kind of shame for me, as a queer person, because I was afraid of it, because I felt judgment. What’s funny about moving to the North, after leaving the South, is finding out how much we all have in common. I’m not talking about when you could find a meme and just pick up on a trend, but the fact that we are generationally mapped in a similar way. I find it super powerful, like, whenever I find other people who grew up in those regions and find out that we have the same kind of structure socially. It’s distant family. Do you know what Outkast said about the South? André 3000 said northern rappers are about skyscrapers, elevation, longitude, and structure. In the South, it’s about the air, wind, and the flow. I never forgot that.”

After the loss of his mother, Satterwhite claims that his work turned towards themes of generation, healing, and resurrection. The ritual movement in We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other implies the human urge to keep trying, to reroute pain. The video starts out with the textures of home—model and activist Bethann Hardison sits in a large wicker chair, fanning herself in front of an engine red house. “You’re not alone / We’re in this thing called love,” sings Patricia Satterwhite. “Love will find a way home.” The viewer gets the sense that this is it: that homespace, an ever-morphing landscape of nostalgia objects, fuchsia skies, and avenging, dancing bodies.