Molly Rose Freeman composes intricately patterned murals that vibrate with energy, which is very in line with her dynamic personality. Freeman is a firecracker, super-engaging, stylish, and magnetic. We met in a coffee shop this summer to discuss her recent live painting installation and exhibition “Hourglass” at Beep Beep Gallery. She told me the best place in Atlanta to get my hair cut, and it immediately was like I was chatting with a cherished friend. Freeman, who has a BA in creative writing from the University of North Carolina at Asheville, has big ideas and no trouble executing them. For “Hourglass,” she was able to team up with her photographer friend Dustin Chambers as he created the concurrent exhibition “Installation Portraits” in the gallery’s back room.

Freeman and I discussed the wonders of fluorescent paint, the allure of bioluminescent bays, the sensory adventures of interactive art, and the prodigious creations that can emerge from collaboration.

Sherri Caudell: How did the collaboration with Dustin Chambers come about?

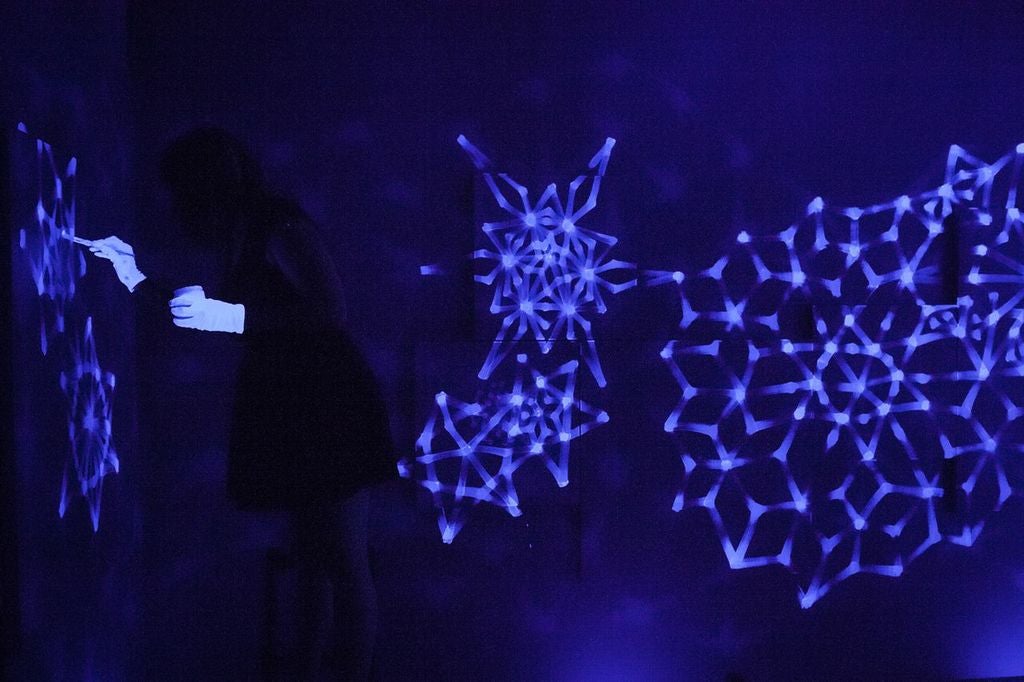

Molly Rose Freeman: I wanted to do a three-walled installation in the front of the gallery and didn’t have a clear idea of what I wanted to do with the back room, but I knew I wanted it to be something that would relate to the front room installation. I was thinking about how this whole show was a way for me to explore what I do normally, which is mural painting, and how that would translate into the gallery setting. I did a weeklong live painting installation for the show. I was painting as people were walking by all the time, and they could stop and watch for as long as they wanted.

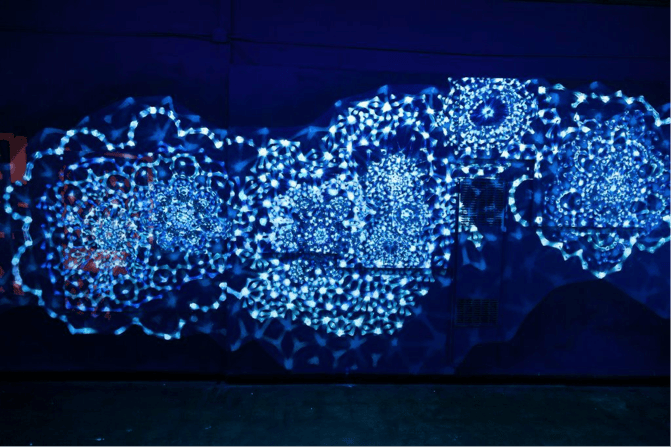

I painted all the walls this really rich royal blue color called Magical Merlin and then painted a grid to start with. There are three different sizes of 14 square canvas panels hung along the walls, and I painted on those as if they were part of the wall. After painting the grid, I plotted out beginning points, seeds sort of, where there are focused areas of light. Then I grew the patterns outward from there, and everything started to grow and join together.

SC: What kind of paint did you use?

MRF: The background was just interior latex, regular house paint. The first layer of UV paint was a mixture of latex and a UV reactive medium, which is clear. Then the brightest paint was two different colors of a special UV paint that I got from a company in California called Wild Fire. I think it’s mostly for movie effects and things like raves. It’s interesting because, the way that you think about color in incandescent light, you have to throw all of that out the window when you are talking about UV light because it’s a completely different spectrum. Like chlorophyll fluorescent is neon red in phosphorescent. Milk fluoresces neon yellow. It’s almost like glazes in ceramics; it’s a chemical reaction.

SC: What drew you to that blue?

MRF: I went to Puerto Rico a couple of months ago with a friend and we went to a bioluminescent bay. We kayaked a waterway that opened up into a big bay full of bioluminescent plankton, and when we looked up there were a billion stars. I wanted to do something to recreate this feeling, not necessarily visually, but I wanted to be able to give people coming into the gallery some taste of that direct experience of light. It’s like a mirroring of these huge systems and then these very tiny systems. That’s partially where the title for the show, “Hourglass,” came from. It also came from the time-based nature of the piece, but part of it was the shape of an hourglass. The show basically came from that moment of experiencing something very large and very small and feeling the connection between those things, these two realms and then this space in the middle where human experience is.

SC: Before working on this exhibition, were you mostly doing murals and public art?

MRF: Yeah, I have a studio, but I like public art. When I was living in Asheville, I had a bunch of studio visits and gallery shows. There is just something about my personality that doesn’t lend itself as well to that practice. I think that part of it is that I like to be very social, and I think I work better collaboratively than I do in isolation. I do a lot of good thinking, get many ideas, and source numerous things by myself. But in terms of the actual creative process of executing something, and bringing things physically to fruition, I like to have other people to work off of. I enjoy patterning because it’s so adaptive, and I think it oftentimes works better when it can react to something, when the pattern comes into contact with a structure or another person’s work. For “Hourglass,” we used public painting to draw people in, and then Dustin photographed the people who were watching.

SC: And that all happened at night?

MRF: Yes, for a week [May 10-17] from 8 to 11pm, we were in there every night. Dustin and I are friends and had worked together a couple of times before, so we bounced ideas off each other creatively. I knew that people would be coming to document from the outside, and I wanted something from the inside too, to get a more intimate view of what the experience was like in the gallery. From the beginning, this was collaborative, even before he started shooting the photos, because he has an eye for light that I don’t have. He also comes from something of a theater background, and he’s worked in computer production, so he knows how to set a 3-D space.

SC: So would you consider it a two-person show?

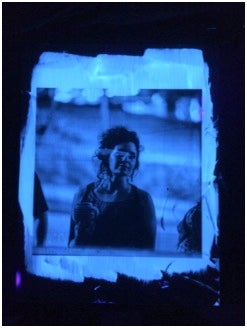

MRF: It did become that. Dustin came in every day with a new idea and these things built upon each other. He really wanted to photograph people looking into the gallery, and he had a black sheet over his head while photographing them from inside. The two of us were sort of locked inside the gallery and we were wearing all black and white gloves so you could see my hands as I was painting and his hands as he was photographing. He got some incredible candid photos because people would look in and they couldn’t see him and they didn’t realize that they were being documented. So there’s a photograph of a guy yawning and a lot of people peering in. Inside the gallery was a bluish-purple glow and then outside, because of the streetlight, it was an orange glow. Dustin ended up cropping the photos really closely, so they are intimate portraits.

Then we debated how to display them. I didn’t want any light pollution in the front of the gallery because I wanted to keep the same mood. He was talking about doing light boxes, and then he was like, “I got it. I can print black-and-white photos on transparencies, and then paint the backs of them with the same paint that you are using to paint the mural so they phosphoresce under the black light.” He went out of town, so I painted the backs of the portraits so you can see the brushstrokes of paint. So it was a physical collaboration too, because it was something that we both had our hands on.

SC: You were still live installing when Beep Beep held Invent Room Pop, the monthly improvised music event curated by avant-garde Atlanta composer and musician Robby Kee, right?

MRF: Yes, it was cool to see people come inside the gallery space and interact with the space, because we had had a kind of sterile, glass-fronted theater box for a week, and the public hadn’t been inside yet.

SC: And then you had a tasting in the gallery one night?

MRF: Yes, we partnered with Dinner Party Atlanta, which is the brainchild of Patrick La Bouff, who started the Lawrence in Midtown. He’s super off–the-wall and very much an idea person. He and Dustin are friends from years ago, when Dustin photographed him for Creative Loafing. These super-fresh, pushing-the-envelope ideas come out of the two of them when they get together. So I had been researching fun food and drinks that fluoresce under black light. I woke up one day and was like, “I want to have a feast in the gallery, but all the food will be glowing.” This was halfway through the install and the show had already opened. We made some little pastries and I did phosphorescent icing patterns on top of them. We did two different kinds of cocktails designed by Navarro Carr, the mixologist at the Sound Table—a vodka lemonade and a gin mojito. Tonic water fluoresces neon blue and then there was something in the mojito mix that fluoresced. The drinks were glowing and we put them into punch bowls, so they were big glowing half-orbs.

SC: I love the interactive aspect of the installation process.

MRF: I want to make work that I would want to see, and I always like work that I can interact with. We’re not just a set of eyes: we have hands, we have noses, and we have mouths. I want to be able to experience installations in as many ways as I can, that is how I make a personal connection to something. I think that when you can feed people, when you can give them some sort of sound to link to the visuals, it’s another way to have an art show. Smells are so good because they’re such memory triggers. That you can bring more than one sense together gives people a fuller experience, which is always going to be more satisfying.

SC: Where do you get your ideas for your patterns? Is it from inspirational images that you’ve looked at?

MRF: Years ago, I was doing more traditional figurative and still life paintings. All of the objects were embellished with pattern. It got to the point where I was like, “This is ridiculous, I don’t even care about the thing that I’m painting. I only care about the patterns.” That was a turning point for me. So I started studying pattern itself really seriously, and I would get source books, like Owen Jones’s seminal publication The Grammar of Ornament. It’s filled with patterns that he’s collected from around the world and throughout history: Ancient Greek, Persian, and Celtic patterns, for example. I would choose a few I thought were interesting. I’ve never felt comfortable using straight edges or compasses, so I would sit down for about six hours and study these patterns and freehand draw them. Once I started to break those apart I was able to internalize them a little bit more and understand the mechanisms of that visual language. Now, I don’t really look at anything— it’s second nature. The circular patterns as opposed to flat allover patterns are really interesting because you get layers of movement— it’s almost like the way a tree grows, it’s got the rings. They have this inherently pulsating feel to them, because that’s how organisms naturally grow.

SC: Are the patterns psychological in a way? Are they a language for you to express your emotions?

MRF: It’s almost like mapping my mental paths. I don’t think as much as I just emote and feel all of the time. By going through the patterning process and by doing this physical repetition, it allows me to slow down into a kind of trancelike state. It’s like a visual tracking of whatever I’m thinking, or whatever I’m feeling at the time. And certain times are much more intense, and I think that you can see that, where points of light are more intense—that’s where I’m focusing more energy. And then there are some that are broader, wider, and more quiet. I don’t know if it’s that direct, but I think that it does show the range of feelings that I can have, especially within a specific time period.

SC: What are you working on next?

MRF: I’m doing a mural for the BeltLine this summer, and then I have a studio at the Goat Farm through the Creatives Project, which is the residency that I’m in. So I want to start being in the studio more, working on some larger paintings. I don’t have another show lined up, but I have some ideas already for the next body of work. I’m going to do a lot of smaller paintings that sort of amass into a larger painting. “Hourglass” made me realize that I want to do more in the direction of performative work, where the collaborator responds to what the other’s doing in a live setting. I’m talking mostly to musicians. I also have a friend who works with computer, so we talked about some lighting design—where the lighting responds to something happening in the space—multisensory, multimedia collaborative installation performances. I share a studio with Lucia Rodriguez; Fatimah Abdullah, who is an animator; and Neda Abghari, who’s the head of our residency. The studio is beautiful, big, and open. Dustin’s studio is also right down the hall, but neither of us has been in the studio that much lately. I slept at Beep Beep for two nights—it was magical, like sleeping under the stars.

Sherri Caudell, a poet and writer from Atlanta, is the poetry editor of Loose Change magazine, published by WonderRoot.