Miami used to write its name in orange ink. Now, our basketball and soccer teams wear pink and blue, and the Florida government owes local homeowners thousands of dollars for chopping down their citrus trees in the early 2000s.[1] The Works Progress Administration–era Miami Orange Bowl stadium, which looked from above like a halved clementine, was neglected for decades before being consumed in the city’s hunger for redevelopment during the 2008 financial crisis.[2] In its place, the dome of LoanDepot Park was laid like an unhatched egg on the horizon of Little Havana, its simple whitewashed walls initiating a new architectural era for a city with a distinct built environment and an economy facilitated by its willingness to demolish and transform itself at a moment’s notice. And yet, the citrus fruit persists, springing up at almost the same speed as new apartment buildings. It ripens for locals under freeways and on dumpsters in gigantic, unmissable, vibrant orange on almost every forgotten wall in town.

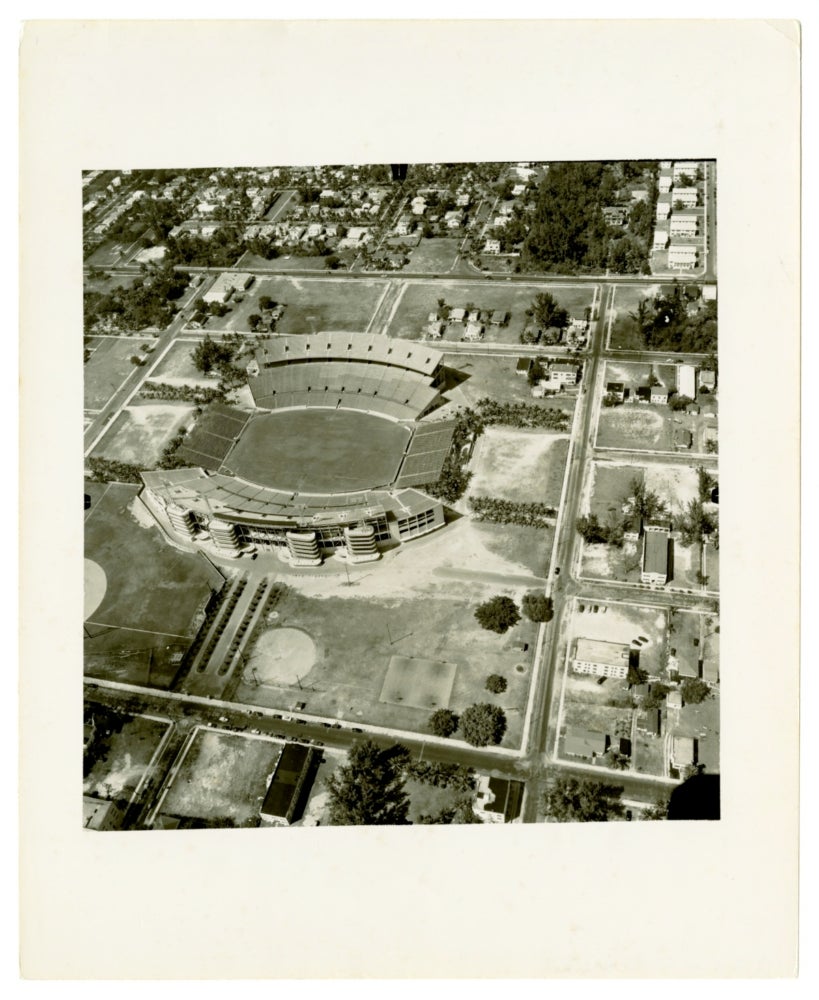

Atomik (Adam Vargas) is one of many taggers in Miami who compulsively mark the urban landscape. Like a chaotic gallery wall, his work mingles with other writers on abandoned buildings known as “penits.” Though the term originated in the 1990s from a building on Fontainebleau Boulevard in Doral that was rumored to have been constructed as a penitentiary, it has since been used to describe dozens of sites that function as temporary canvases for communal works of hyperlocal art. These contributions are now so successfully camouflaged in the landscape of the city that they have become essential to its character.

Because historic buildings are often neglected in Miami, Atomik has painted on many razed structures iconic to the city. In 2014, his work could be seen on the walls of the Miami Herald building, specially fortified to protect the presses against hurricanes in 1963.[3] They were no match for the casino company that bought and destroyed the structure ten years ago, leaving a parking lot in Downtown that is currently for sale for more than a billion dollars.[4] Other buildings are left to rot to avoid preservation costs, and the lack of memory or care for their history allows them to be transformed, however momentarily, into something new and beautiful by artists like Atomik. There is no grant money funding these projects, but there is community dedication. One of the largest and most used penits in Hialeah had several inches of layered paint on its walls at the time of demolition. The building had begun as a contaminated Superfund site due to chemicals from the printing of Hustler magazine there in the 1980s.[5]

Wynwood Arts District aestheticized the graffiti scene in Miami, inviting international artists and developers to play with the style of DIY graffiti culture that local writers (the community term for street artists) had originated. These artificial installations, like Wynwood Walls, directly evoked the space of the penit for touristic consumption. Atomik himself admits that his work benefitted from the gentrification of Wynwood. His rapidly multiplying oranges have become a symbol of the city, and an accepted part of everyday life as well as a reference point for visitors. But even in Miami, which has built an international reputation for street art, Atomik is regularly arrested when painting, particularly because his work adorns occupied as well as abandoned buildings.

As a tribute to the demolished Orange Bowl stadium, Vargas painted his first version of the orange character originally based off Obie, the mascot of the Orange Bowl, on the side of the derelict Miami Modern Furniture Store in North Miami Beach, the artist said in an interview. Now, all that remains of the building and the mural are two so-called MiMo arches visible from the Golden Glades Interchange. With his old crown replaced by a teardrop and a stylized grin, Atomik’s character can now be found hiding in businesses even when you’re off the streets. “So, as a graffiti writer you’re kind of trained to just . . . bomb. And copy and paste and put your name everywhere,” said the artist. “So, I took my graffiti habits and my graffiti approach and applied it to this character. And it’s kind of a relentless campaign that just never stops.” Atomik’s bombing recalls the public branding campaigns of companies like Coca-Cola. But money can’t buy this kind of advertising, or the position that the character can hold in the psyche when seen day after day after day. By camouflaging his work within the urban environment, Atomik has created a character that is arguably more iconic than any singular building in Miami’s rapidly evolving skyline.

Downtown Miami and Brickell may be a rare trip for many people who live in the area, but locals from Homestead to Hollywood Beach know Atomik’s work on sight. At least until it disappears. “A lot of my work gets painted over, knocked down, demolished,” he has said. “I’ve been doing them since 2008, 2009, 2010, and I don’t have any from that initial run that are still up. . . . Canvases, that’s a different thing, people have them in their collection. But work on the street doesn’t last long here in Miami.” Atomik himself often paints over other artists’ work, especially if it is damaged, though he tries to completely cover it when he does. Many of his still extant pieces linger above the freeway and Metrorail tracks in “billboard” bombing locations, becoming new landmarks in themselves.

Over the intersection of Biscayne Boulevard and the 79th Street Causeway, his moniker and signature orange are visible for miles in three directions. The history of the structure bearing his work feels comically representative of the city—the building began as an office of the Gulf American Land Corporation, which sold swampland to gullible Northerners,[6] then became the local headquarters of Immigration and Naturalization Services. For decades, it was a site of pain and historic protest for many in the Miami community—lines often stretched around the block. In 2000 during the nationally controversial Elian Gonzalez adjudication, a plane was chartered to fly around the building to advocate for the boy to remain with his relatives in the United States.[7] Eight years later during the same financial crisis that took the Orange Bowl, the government left, taking with them the iconic gold MiMo aluminum siding that distinguished the building from the newer towers up the boulevard. A few years after that, Atomik was able to access the roof with another artist. On the west side, they painted on a small ledge against a hundred-foot drop. “It was crazy . . . and I never would have thought it would last this long,” Atomik reflected. Painted on three sides of the roof, the unmissable mural is now one of his oldest pieces that still exists. After fifteen years of vacancy, the building is as likely to be called the “Atomik building” as it is the “INS building” by the thousands of commuters who pass by the work daily.

Once you start to recognize Atomik’s signature figure, it’s difficult to go anywhere in Dade County without encountering it. He also paints on canvas as well as foraged street signs and other Miami rubbish, and his work can be found on keychains in tourist shops and hung on gallery walls. Each Friday night, he drops a free piece of art in a different neighborhood for fans or passersby to pick up. Because of the approachable price point of much of this work and the sheer volume of oranges that Vargas has painted in the last fifteen years, it’s not unusual to find yourself confronted with a smiling Atomik figure within private residences. The color orange has been used in construction for decades because it demands attention, and passersby wearing Atomik’s bright shirts or spray-painted shoes instantly stick out—even in the colorful world of Miami.

The ubiquity of his character can feel unsettling. In some neighborhoods, it’s difficult to escape its orange gaze. This time of year, even the jack-o’-lanterns on neighborhood stoops recall the ghoulish grins. But Atomik’s character has also grown beyond the city; Vargas has painted his orange in countries across the world, and his style of “bombing” was influenced by other artists in the international and local street art communities. When I lived in Chicago, I would visit his mural because the orange itself was so deeply associated with the character of my hometown. More than a thousand miles away from the neighborhoods where I first encountered his symbol, I felt I was still in on a private Miami joke.

[1] Associated Press, “Florida faces $1.2 million verdict for killing citrus trees,”Tampa Bay Times, June 8, 2022, https://www.tampabay.com/news/florida/2022/06/08/florida-faces-12-million-verdict-for-killing-citrus-trees/.

[2] Drew Maglio, “An Ode to the Orange Bowl,” State of the U, November 22, 2019, https://www.stateoftheu.com/2019/11/22/20965502/miami-hurricanes-ode-to-miami-orange-bowl-stadium-game-hard-rock-stadium-super-bowl-national-title.

[3] Andres Viglucci, “Miami Herald’s iconic building is history,” Miami Herald, April 21, 2015, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article12269438.html.

[4] Jeff Kleinman, Photos: Waterfront land at one Herald Plaza in Miami, Miami Herald, April 27, 2023, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/downtown-miami/article274777916.html.

[5] I am grateful to MiamiGraffiti.com for collecting much of this history.

[6] Ana Claudia Chacin, “How the revamp of Miami’s INS Building became an epic disaster,” Miami Herald, April 11, 2023, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/immigration/article272336928.html.

[7] Ibid.