“You didn’t see me on television, you didn’t see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come.”

Ella Baker

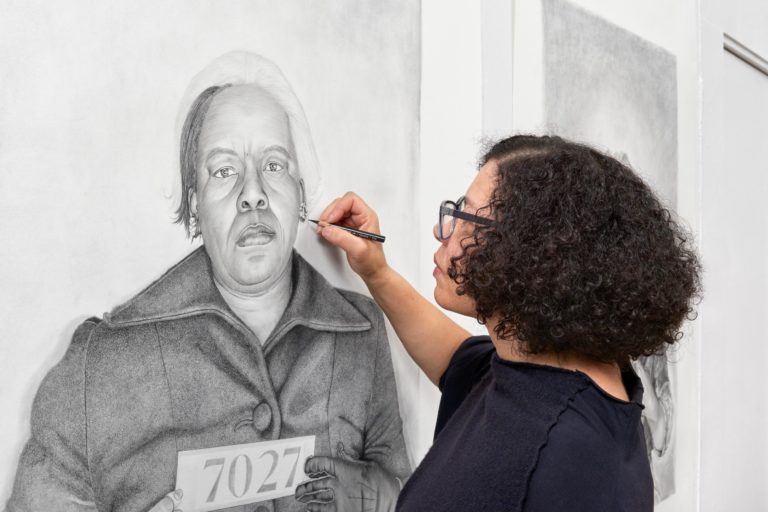

Lava Thomas’ intimate portraits of figures who are often excluded in conventional retellings of African American history demonstrate the artist’s virtuosic ability to see people for who they are, not merely for who they are purported to be. In Lava Thomas: Homecoming, exhibited at the Spelman Museum of Fine Art from August 17—December 3, 2022, three bodies of work come together in a demonstration of Thomas’ deep commitment to revealing personal and cultural narratives that deserve recognition and warrant critical attention.

This fall, I met with Thomas and Dr. Bridget R. Cooks, curator and Associate Professor of Art History and African American Studies at UC Irvine. We discussed Southern family origins, the supposed sanctity of photography, and serendipity’s sweet magic, an idea apropos to the timing of this interview’s publication. Earlier this month, we celebrated the sixty-seventh anniversary of the Montgomery Bus Boycott campaign that lasted from December 5, 1955 to December 20, 1956. In the following conversation, which offers an extensive deep dive into the exhibition’s background and its historical resonances, I speak with Thomas and Cooks as we reflect on the Black women and men who have lit the paths before us, paths that have often led us back home.

Bryn Evans: This exhibition is the Spelman Museum of Fine Art’s first show since the institution reopened due to the ongoing pandemic. After debuting in Montgomery, why was it important to bring these bodies of work to Spelman?

Bridget R. Cooks: We really consider Spelman the Mecca for Black American women. It’s such an honor to be involved in a process of sharing Lava’s work in that space. It’s incomparable — there’s no place like Spelman, and we knew that the community would understand the significance of having Lava as a Black woman artist making the work and appreciate its gravitas. The level of conversation and questions that the students and faculty had in particular was head and shoulders above the kind of conversation that you’d have presenting this show at a mainstream museum.

Lava Thomas: I’m so incredibly honored to have my work at Spelman and to be in a space where Black women’s worth, value, and excellence is fostered. It means so much to me as an artist, as a Black woman, and as someone whose main focus is portraying Black women through portraiture.

BE: I was so lucky to be able to spend a semester at Spelman via domestic exchange. And I agree that the conversations you’re able to enter with are a lot different than those that are encouraged at predominantly white institutions. Blackness is not an anomaly or an outlier or anything like that at Spelman. Instead, the college is a space where we are encouraged to discuss its nuances.

Before Homecoming, The Black Index, debuted in 2021. That show considered Black self-representation, particularly in response to the violence of colonialist imagery and the dehumanization of the Black body in fine art. Bridget, you dedicated The Black Index to your mentor David C. Driskell. Knowing Driskell as a founding father of African American art history, I’m interested in hearing more about how he influenced your thinking around world-making and arts capacity for structural change.

BRC: I was so influenced by David C. Driskell. He had one of those personalities that made you feel like you were close, and there are hundreds of us that feel like we were close to him. I used to tell him that he seemed to be whatever age I was. He had this amazing way of communicating with people. He also reinforced the idea that there’s room for everybody in terms of Black artists, art historians, curators, etc. There’s so much work to be done, and no one person can do everything — so welcome people, help prepare them, be a resource, do what you can because there’s room for everyone. He was exceptional in so many ways: as a curator, as an institution builder with the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland College Park, as an artist. He really showed me how dynamic the field is and how you need to cultivate all of your talents.

BE: I want to dig a little bit deeper into The Black Index, because that exhibition acts as a sort of predecessor to Homecoming. Was The Black Index the first time you both began working together. How did you meet?

BRC: I think it was at MoAD (The Museum of the African Diaspora) in San Francisco. And Rena Bransten, Lava’s dealer, had sent me a catalogue of her exhibition with the mug shot portraits. Then Karen Kienzle, who is the Director of the Palo Alto Art Center, had asked a colleague to send it out to me.

LT: All of that happened without my knowledge. We met at a conference at MoAD. I can’t remember the topic of the conference, but Karen introduced us. Shortly after that, Bridget invited me to participate in The Black Index. That’s when we first began working together. The experience was absolutely amazing. The show traveled during the pandemic, so Bridget created online programming around the exhibition that was just stunning. And I believe you received an award for that?

BRC: [Laughs] Yes, thank you. It’s true. Because of the pandemic, we had to shift our whole concept of what programming would be because we couldn’t have events in-person. I was able to raise enough funds to hire filmmaking teams to make different films featuring the artists, and then some of the artists were also involved in online conversations. Those were really fantastic. They’re all on theblackindex.art website. I did receive—along with my exhibition manager Sarah Watson, who’s the chief curator of the Hunter College Art Galleries—the Award for Excellence in Online Programming from The Association of Art Museum Curators.

BE: Period. Lava, I also want to discuss Decatur (2022), which recently debuted at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Art. With this work, I’m thinking about Southern Black archives and the relationship between ancestry and memory. I would love to hear you talk more about the impetus for this body of work.

LT: I grew up listening to my grandmother’s stories of her childhood in both Decatur and Vernon, Texas. And so a lot of that family history was passed down to me orally. My grandmother would take the Greyhound bus and back travel to Decatur and Vernon. She would do that every year, and she never took any of her children or grandchildren with her. This was her time to reconnect with family and friends. She always came back refreshed and full of more stories.

I visited Decatur, Texas for the first time in 2019. I was invited as a visiting artist at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. During my time there, I traveled to Decatur to look up some of the landmarks that my grandmother mentioned. I found them, including the street my family is named for and the segregated one-room schoolhouse that my grandmother and my great-grandmother attended. It only went up to the fifth grade, so they moved to Vernon in order for my grandmother to continue her education.

A few months later, completely out of the blue, I was contacted by the Wise County Genealogical Society to attend the posthumous military funeral for my great-great-great-grandfather. My grandmother didn’t really talk about my great-great-great-grandfather, so I didn’t really know very much about him. When my family traveled to attend the funeral, I discovered so much information about him. He served in the Civil War as a private in Company K, 5th U.S. Colored Infantry. When he was discharged, he settled in Decatur, Texas as a free man and changed his name from William Eckler, the name of the man who enslaved his father, to Charles H. Arthur. Years later, when he applied for his military pension, the process was complicated because he had changed his name. His assertion of self-autonomy and self-sovereignty complicated his ability to receive his pension, and he waged a legal battle that lasted for almost a decade, generating a document archive that tells his life story. The photograph that was given to his fellow soldiers to prove that he was in fact William Eckler is the basis for the portrait. That is the anchor for Decatur. I’ve also included fourteen of the documents, affidavits, and depositions, in his own words, in my great-great-grandmother’s own words, and in his fellow soldiers’ own words, that really tell the story of his life and his military service.

BE: Thank you so much for shedding light on his story. It seems like such serendipity that you would be invited to the memorial service after your visit to Fort Worth.

LT: Honestly, it was crazy when I think about it. But now at this stage in my practice, I really trust the process. Because things like this happen all the time. All I have to do is pay attention and follow my own curiosity.

BE: The earliest work in the exhibition is Looking Back and Seeing Now. It is a gorgeous tribute to church mothers, deaconesses, ushers, and first ladies, which are all women that I grew up around. It feels very close to home. With the title, you’re drawing on the Black Pentecostal tradition of call and response, as well as the Bono Adinkra symbol of Sankofa, which I know is significant to you, Bridget. The work is kind of like a floating altar. I’m reminded of my upbringing as a preacher’s kid, a preacher’s grandkid, and a preacher’s great-grandkid.

BRC: Wow, that’s a lot. Let’s think about that for a second.

BE: I come from preachers and teachers, specifically within the Church of God and Christ. That’s the denomination that I grew up in. My grandfather wanted a peaceful transition of authority, and he was looking for someone who would be willing to take up the church. My father told him that he would accept the calling. I grew up in a small, close-knit church. So there is a sense of familiarity and comfort, where church is a second home for me and I’m very grateful that I’ve had that experience. I also remember how it felt when I realized that this place that I considered a home, that I considered holy, was also targeted with acts of terrorism. I remember learning about the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and Mother Emanuel AME.

Looking Back and Seeing Now exhibited at the Berkeley Art Center, a month after the Charleston tragedy. What was your intention with this installation? Did you find that it took on new meanings in the weeks and the years that followed?

LT: When the tragedy happened, I was putting the finishing touches on the exhibition and getting ready to install it. Going back to what you said earlier about the Black church, it makes me so happy to hear that you see the exhibition as a tribute to the church mothers, the deaconesses, the ushers, because that is who my maternal ancestors were. My grandmother was the church pianist and a choir director. My great-grandmother was the organist. My aunt was the usher, and I always say that I was raised in the bosom of the Black church, even though I’m not a church-going woman today. I’m incredibly grateful that I grew up in that tight-knit family because the community was very much like a family and a second home. My grandmother was part of the Church of God in Christ, but the rest of my family were Baptist. So I grew up in both traditions. And there was in my family, [chuckles] there was always some tension.

BE: [Laughs] I know it.

LT: There was some tension because my grandmother, you know, being from the Church of God in Christ, was very strict and sort of judgmental. The rest of my family were all very social and belonged to a huge Black church in Los Angeles. My grandmother always liked to belong to small storefront churches where she felt she could make the largest contribution.

The intention for Looking Back and Seeing Now really evolved over the period that I created the work. It grew out of finding my grandmother’s photo album. I was looking for sheet music, and her home is still in our family. I was looking at her piano bench, and I found her photo album. She had passed a decade prior, so it was a big surprise. The photo album was so old and brittle that when I opened it, it was literally falling apart. The women’s photographs that I looked at when I initially opened the album seemed to stare back at me with such intensity that I knew I had to create a body of work around that.

I created those initial portraits very large. And I thought a lot about the history of portraiture—when Black people have been historically portrayed, it’s been in a secondary position and a position of subjugation. So I wanted to make these portraits very large, and I wanted to make visible what had been hidden for such a long time. As I was putting the finishing touches on that exhibition, the Charleston massacre happened, and it did immediately bring up the Birmingham bombing. It also brought up other acts of violence against Black churches, and the grief and the rage was just overwhelming. I didn’t want to visualize the grief and rage. Instead, I wanted to create space for contemplation, a meditative space, so I transformed the gallery into a space that would evoke the prayers, the resilience, and the strength of my foremothers who were Black women from the South.

BE: Thank you. I love the work, and I am so excited to bring my family to see it. My mama always packs a tambourine in the car trunk.

LT: I wanted to use artifacts from that time in my life, like artifacts from the Black church, instruments that had real meaning for me. Playing the tambourine in church for me was just ecstatic, right? I grew up immersed in that music. The Sunday after the Charleston massacre happened, people took to the streets playing bells—they took to the streets playing tambourines, and it was this act of defiance. As if to say: you can hurt us, but you can’t destroy us. In that moment, the tambourine became a unifying symbol. It was a symbol of defiance. It was a symbol of resilience.

BE: Yes. And you think even of the war cry, you know? Bridget, how was the installation process? The work really activates that exhibition space.

BRC: We are grateful for digital technology and telecommunication because we had to do it over FaceTime. We had a great team of people in the gallery. Liz Andrews, the Director of the Spelman Museum of Fine Art, is someone who I knew from Los Angeles. It was great to have her and her curatorial assistant, Jasmine Wilson. And then there were two preparators. You never know who’s going to install the work, but I have found that people have so much respect for it. The labor and the care that goes into making the work and preparing it has an impact on viewers, and they understand it has value. Everyone wants the work to look as good as possible in its unique space. This is the sixth institution in which I’ve been able to present Lava’s work, so there’s a kind of agreement and care that goes into installing the work. Having said that, we all have to be flexible to an extent because each gallery is really different. The shape of the inverted pyramid of tambourines is different from where they were shown before. You come to terms with how the artwork is going to take shape and how people will experience it. There’s a way in which you’re part of a discovery process. With the Spelman Museum iteration, we really wanted to make sure that the tambourines were a vista, something that people could see through the glass doors before they even got to the space itself. It would be something that piqued their interest and drew them into the gallery. And I think it does that really well.

BE: It does. Theaster Gates: Black Image Incorporation preceded Homecoming at the Spelman Museum. With that show, there was a similar sense of solemnity and sacredness to the archival images. For instance, you had to wear white gloves to enter the space. I love that spatial continuation, because both shows offer viewers an opportunity for exploration. Lava, in a conversation with Faith Adiele, you describe yourself as a seeker. Can you tell me more about that?

LT: I mentioned earlier that I’ve come to trust my creative process and that the work offers its own path. As long as I am paying attention and following it, I discover something new. When we spoke about the serendipity of my travel to Decatur as a visiting artist, and then visiting Decatur two months later to attend a military funeral, those events led to this body of work that taught me a lot about my family history. My family’s origin story begins in Decatur, Texas, because my great-great-great-grandmother was enslaved there. I’d have to do a different kind of research to find out what her actual origins were. Looking Back and Seeing Now was the result of a discovery as well—looking for my grandmother’s photo album and that generated another body of work.The Montgomery Bus Boycott portraits were the result of looking at women activists in the United States and discovering mug shots that were with the famous mugshot of Rosa Parks, and not knowing who these other women were. My research led to Jo Ann Robinson’s memoir. It’s just a series of discoveries, a series of searches, and a path that the work takes me on.

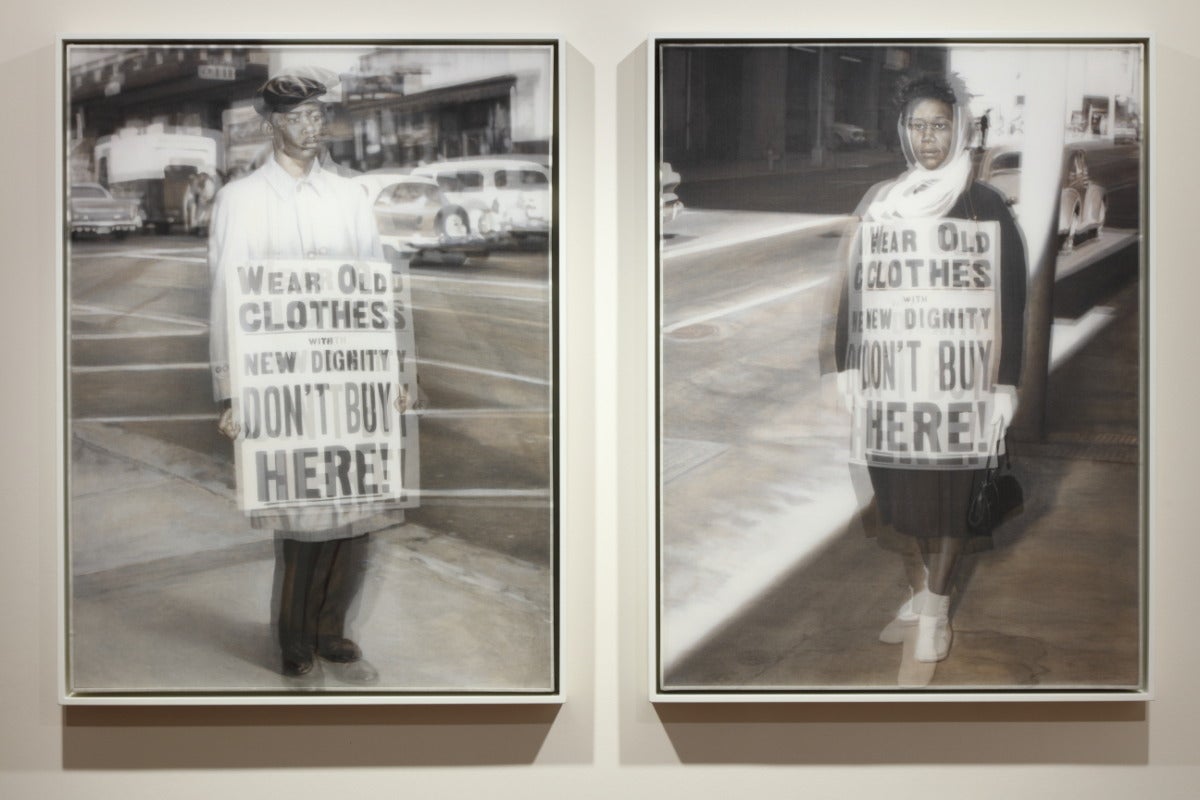

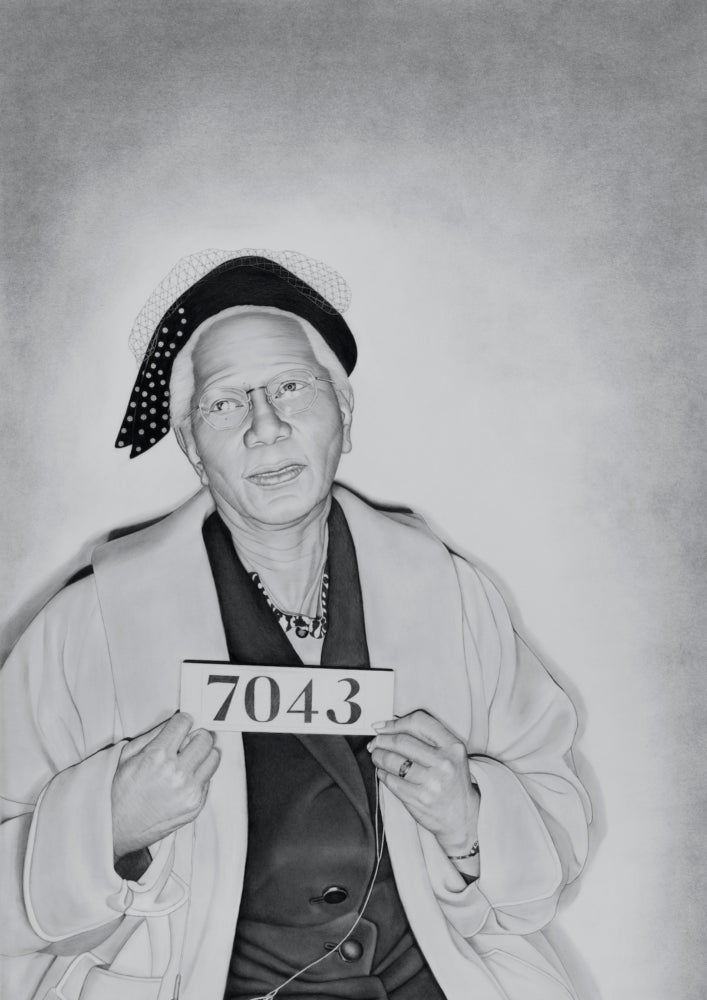

BE: Jo Ann Robinson is really the mother of the Montgomery bus boycott. She used her position with the Women’s Political Council to distribute thousands of notices calling for a boycott after Rosa Parks’ arrest, and the campaign commenced only a few days later. Some viewers might find the mug shot portraits objectionable, preferring instead to imagine the women outside of a carceral state. What does the context of arrest provide the portraits?

LT: I wanted to tell the story of the women’s bravery, sacrifice, and willingness to break the law to end Jim Crow segregation. I also wanted to honor them in the moment that they were being arrested and when their image was actually being added to the criminal archive. Mug shots are meant to criminalize and to dehumanize, but I’m subverting that intention by transforming the mug shot into commemorative portraiture. And I’m creating each portrait with such care, respect, admiration, and regard. That’s what the state was trying to strip from them. The portraits also reveal the ways that the women themselves subverted those attempts, by the way that they dressed and their refusal to hang the booking numbers around their necks. That story really wouldn’t be told in a portrait if we were looking at a conventional portrait and then reading that information on the wall text.

BRC: It was really inspiring to study Lava’s work because you could see how these were everyday people, in a way. That is how movement has to happen. When we look at the details that are restored in Lava’s work, as a result of the research that she did and the time that she put into making the portraits, we can really think about each woman’s story and their personal archive. Lava’s portraits force us to stop and wonder— how did you get that detail? How does that lace look like that? How did you get the hair? We wonder about the artistic process but then we also wonder about the women themselves and see that they have their own lives. When I got to Spelman, I was looking at them all over again and noticing things for the first time. I found myself totally drawn into the works, as if I was seeing them for the first time. The most recent studies in museums say that viewers will look at an artwork for 1.2 seconds, and I just don’t think that’s happening with this exhibition.

BE: The pencil drawings are invitations for slow looking. It’s really interesting, given that, with mug shots, you almost don’t want to meet the gaze of the person who is deemed criminal. The very act of looking becomes a transgression. Lava, your use of pencil and the enlargement of these portraits is really subverting that detached social interaction by saying: “Look a little closer. Come right here.”

LT: The way that they’re drawn, with the accumulation of hundreds upon hundreds of strokes, is really a metaphor for sustained labor over time. The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted for over a year. It was thirteen months, and it took that long for segregation on Montgomery buses to be deemed unconstitutional. My technique, in addition to hanging the life-size portraits at eye level, encourages viewers to engage with them individually and really recognize the humanity of each woman. Each expression conveys so much emotion, and there’s a vast range of emotion that’s expressed. From Jo Ann Robinson, who looks like she’s posing in a conventional photograph, to somebody like Lottie Green Varner, who has this look of defiance. It is important for viewers to take in the humanity of each woman, despite the fact that the mug shot’s intention is to dehumanize them.

I would like us to be able to imagine how it is that we are here today as a direct consequence of the collective imagination of poor Black women who walked.

BE: I am thinking about this difference between the mug shot and the portrait, and it’s reminding me of the idea of a photographic memory. We insinuate that photography holds a certain kind of truth when we say that someone has a photographic memory, as if they’re remembering a moment or scene exactly as it appeared. But I believe that photographs can lie. There’s a lot left out of the frame. Do you all think that photographs are reliable?

BRC: I always ask my students to think about what happened in the six minutes before the photograph was taken. The exercise is something that I do to try to imagine what happened leading up to the exact moment, since those things are often left out of the picture. So much of seeing is interpretation. And so I don’t believe in objectivity in photography because photographs are taken with a machine of some sort, and yet, there is a person behind the machine who makes the decision. I think it is really quite subjective, and because of that, I don’t think that they’re completely reliable. On one hand, let’s say you take a photograph of your room. You’re looking at the picture and may notice things that you hadn’t noticed before. There’s ways in which photography makes some things visible, but it also makes some things invisible. A perfect example is the mugshot portraits. If you were to look at some of the original pictures, you’d see how so much information isn’t there, how it doesn’t tell the whole story. Part of that is emotional and spiritual. It’s about the conversations that we’re having in front of Lava’s work that we couldn’t have if we were only looking at the mug shot. In that way, they’re also recontextualized. We’re not looking at them as solely objects of persecution within the sacred space that Lava and the curatorial team have created at Spelman. All of that changes photography and maybe answers the question by saying that photography is not reliable.

BE: Lava, would you like to add anything?

LT: Bridget said it all.

BRC: [Laughs] I could go on and on.

LT: I use the archive because I want to relay something specific, so I’m always making those changes. I’m always adding information and tweaking the information that I find in the photograph. I’m not really thinking about the photograph’s unreliability. I’m thinking more about how I’m going to use the source material to convey something very specific that I want to say.

BE: Right. And recognizing that the photographer is doing that as well.

LT: Yes, particularly with mug shots.

BE: Last year, the Getty Research Institute hosted programming for The Black Index, including your conversation with Dr. Leigh Raiford. In closing, you quoted Angela Davis, a Birmingham native. She provides an invocation to the Black women who organized the bus boycott. “Not only Black women,” she points out, but “poor Black women. I would like us to be able to imagine how it is that we are here today as a direct consequence of the collective imagination of poor Black women who walked…” How does Homecoming respond to Davis’ call for a class-conscious understanding of the present day? The fact that this survey is exhibited in Atlanta’s West End, albeit within the context of an elite college, rather than in Midtown or Buckhead seems necessary and intentional.

LT: When I approach my work, I always think about accessibility. One of the reasons why I work in portraiture is because everyone can understand it and appreciate it. You don’t have to have a degree in art history or cultural studies in order to appreciate my work. It offers various levels of entry. You can appreciate the skill level, you can even go further and appreciate the history that I’m revealing, but it has something for everyone in all age groups. That’s not necessarily true for all museum exhibitions. I’m portraying Black people so that when Black folks visit, they immediately see themselves reflected in the work that’s hanging on the walls. They feel a sense of belonging.

Going back to the Montgomery Bus Boycott—its success relied on the entire Black community of Montgomery. The majority of folks taking the bus were domestic workers. Without them refusing to take the bus, the Montgomery Bus Boycott would not have been successful. It also required Jo Ann Robinson, who was a professor of English at Alabama State College and president of the Women’s Political Council, to have the foresight, leadership, and initiative to organize that initial one-day boycott. It really took an entire community, slicing across class lines, for the boycott to be successful. You had to have folks who had cars in order to drive folks to work so that they wouldn’t need to ride the bus. Any movement for change’s success is dependent on the entire community across class lines. Everyone has a role to play.

BRC: Because I study museums, and I’m so interested in museum history and Black people, I might write about the difference in contexts of showing Lava’s work at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts and at Spelman. They are quite different spaces. The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts does not have a strong record for featuring the work of Black artists. And it’s a beautiful space, though the city buses will not drop you off at the museum. It’s not a place that’s frequently visited by Black people. When I think about the show at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, I think of it more as an intervention. It is a different kind of exhibition than what is usually shown there, but they have shown Lava’s work before in a group exhibition.

LT: Yes, Personal to Political traveled there, and I was a part of that show. Bridget, you’re absolutely right when you talk about the inaccessibility of the Montgomery Museum of Fine Art. You drive down this long boulevard that’s tree-lined, and then you’re driving through rolling hills, and then you see the lake, and then you see a very stately building with columns. It all speaks to a kind of exclusivity. So for the opening night of Homecoming, to have families that were descendants of the women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, to have all these Black folks enter into the space—the pride and the joy was palpable.

BRC: It meant something very specific to show that body of work in Montgomery. There was a feeling of a kind of justice, and that is where the title of the show came from—homecoming. It was initially about showing the portraits of the women in the city where they had lived and where they were arrested. It takes on another resonance as a homecoming when it goes to a space that protects Black women. Both spaces are important. Mainstream museums have a very long way to go in terms of social equity and recognizing Black value. Now, I am watching the museum to see what’s going to happen next, because it seems like they’re doing exhibitions that are addressing anti-Black racism and starting to include topics that are relevant to African American people. My primary job as a curator is to make the artists happy. I work with artists who I want to make happy because I think their work needs to be seen by everybody. The other part of my work as a curator is interested in pushing. With Lava’s work, you can push because it’s so strong in multiple ways. It’s possible to create a situation with art by the right artists, to allow the work to signify and reach people who maybe won’t go to Spelman. I like to have a broad audience, but I also realize that because museums have always been segregated, either officially or unofficially, the work has to go to different kinds of spaces.

BE: It makes so much sense for the exhibition to begin in Montgomery, and it sounds like the opening night was very spiritual in a way.

LT: It was celebratory. Spiritual really is the word, in that the spirit addressed the idea of justice. We were all teary-eyed. I appreciate both experiences and also understand the necessity of having the work in each venue. I’m really inspired by Elizabeth Catlett’s work and her ability to marry technical virtuosity with content in regards to Black women and our lived experience.

BE: The immutable photographer, curator, and scholar Dr. Deb Willis was an early mentor to you, Bridget. She supported your development as a curator, and you found inspiration in her books. A few months ago, I was chatting with Tiana Webb Evans, who was also mentored by Willis, and we were discussing the significance of finding mentors who encouraged our contributions to the field. How has this community-mindedness informed your teaching and curatorial projects? I’ll also extend it to you, Lava, since I heard you describe Bridget as a mentor for you.

BRC: Dr. Willis is someone who gave me a break. She gave me a chance to succeed or fail. I knew her first through her book on J.P. Ball and Reflections in Black. I was able to introduce myself to her, and she invited me to apply for a position working with her at the Smithsonian on the National African American Museum Project. She wanted me to help create and support the first exhibition that they were going to put on. Later, that project became the National African American Museum of History and Culture. This was over twenty years ago. Deborah Willis is a woman of few words, and you listen very closely. You want to make her proud of you, and you don’t want to make her regret giving you a chance. So much of working with her has taught me how important it is to be thorough in your research, to try to be one or two steps ahead as much as you can be. And a lot of that comes with experience—you become better and more skillful. She’s someone who, just with a look and very few words, communicates expectations. I’ve never met anyone quite like that, especially not in the field. Her mentor was also David C. Driskell, so I got a double dose of support. At some point I felt like we were all doing the work, even though they were mentors. She had the similar ability as Driskell to generate at least one generation, of young Black women in particular, who feel that she is their mentor. I mean, how is that possible? She’s powerful and influential in that way. I still feel, of course, that I’m being mentored by her. I also feel like, at some moments, we’re peers in the field, that we’re both well-respected and responsible figures in this work. I mean, the only reason really that I’m in this whole profession is because of her.

LT: Wow. That says so much.

BRC: It really is true.

BE: I feel the same about making her proud. One of my first opportunities in print publishing, Women and Migration(s): Volume II, came out of my relationship with Dr. Cheryl Finley at Spelman, and it is co-edited with Dr. Deborah Willis, Dr. Kalia Brooks Nelson, and Ellyn Toscano.

BRC: Dr. Finley and I are sisters in that way. The content of our work is different, but we’re both professors, we’re both curators and we both have had Deborah Willis as our model. I don’t even remember the first time I met her, but either Deborah Willis was in the room or within the first five minutes, we mentioned that we worked with her. Then it was like, oh, okay, we can expect the same kind of insight from each other.

LT: Both of you are so fortunate. Because I attended predominantly white institutions to study art, where there were no Black professors or Black women as faculty to take me under their wing, I’ve had to go out and find my own mentors. And then I have mentors from afar, people who I admire or who have been influential, but not necessarily hands-on mentors. And then I look for folks, like Bridget, where there’s just a certain level of professionalism and a very high standard. This idea that there’s room for everyone goes so against the way that artists are trained. Despite all of that, there is room for everyone. I’ve been fortunate to find levels of real generosity and folks that have been willing to take risks with my work, so I appreciate you, Bridget.

BRC: I appreciate you, too. You pick and choose who you work with, and that makes it such a pleasure.