Georgia-raised, Nashville-based photographer Kristine Potter’s project Dark Waters has borne large scale photographic prints, a video piece, and a book by the same name published by Aperture in 2023. Over eight years in the making, the project re-animates the murdered women from historic murder ballads vis-a-vis studio portraits. These figures are presented alongside images taken in and around the Southern locations named for these violent acts: Bloody Fork, Troublesome Creek, Blackwater Swamp. Potter’s work is currently on view in Atlanta at High Museum of Art’s exhibition Truth Told Slant and in Bentonville, AR, in a solo exhibition at the Momentary, Kristine Potter: Dark Waters.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

JENNIFER DUDLEY: I had been lucky enough to see your show at The Institute of Contemporary Art in Chattanooga back in—

KRISTINE POTTER: Two-thousand-and-COVID?

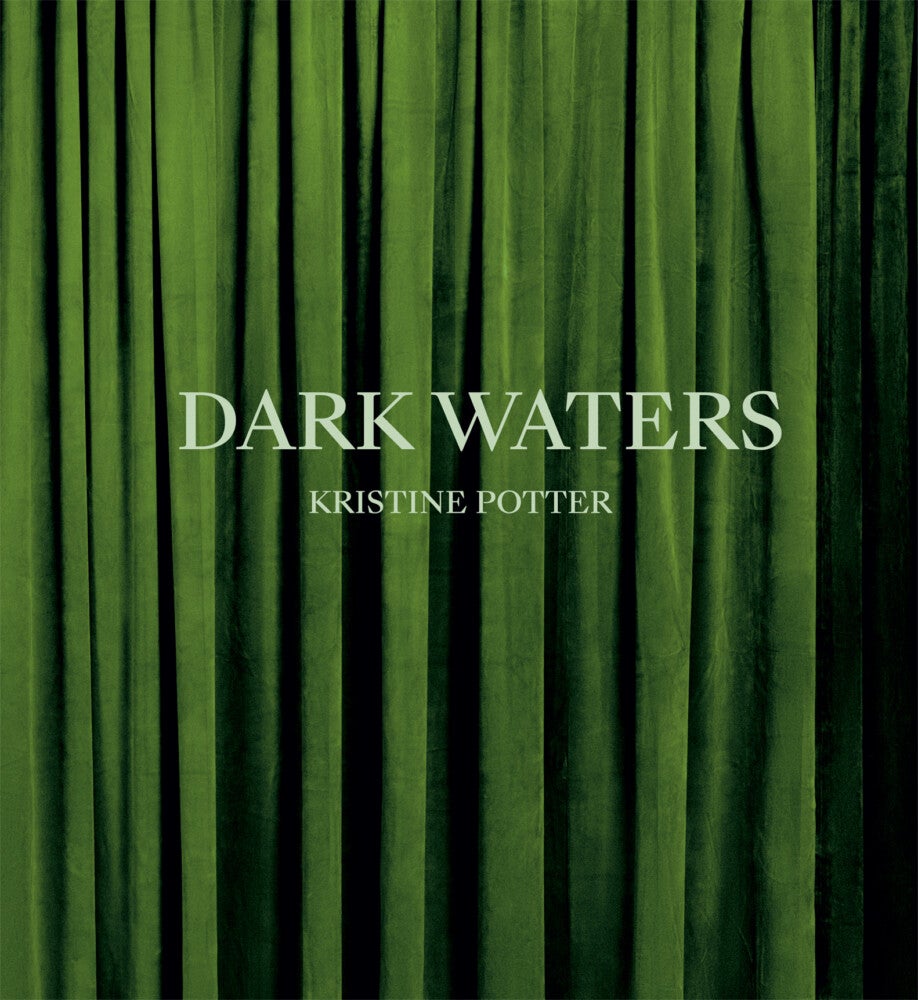

JD: Exactly! And the exhibition was black and white, no color. But as soon as I see your new book, Dark Waters, there is this shock of a green cover. And it’s amazing. Since then, I’ve heard you talk about the color of the cover in terms of the forest canopy, that green curtain that happens in the landscape. I love that connection. But my initial connection to this gorgeous green curtain was to this Bronzino painting that hangs in the Frick, the portrait of Lodovico Capponi. And to Holbein’s Ambassadors. There’s something very painterly about that cover, but then you open the book and the images are speaking a different language, a photographic language. You have a background in art history—you got a BA in art history at the University of Georgia along with your BFA in photography. What is your relationship to that painterly language?

KP: It’s a good question. I actually worked at the Frick for a year.

JD: Oh, I had no idea!

KP: Yeah, and I had this desk job, digital asset management. I basically was putting metadata on files all day and it was just mind numbing. So I would leave my desk every day, at least twice, to go roam the Frick and visit “my Vermeer,” I would say. I love painting and I love the history of Dutch painting and I love the portraiture—the lighting that comes from the Dutch masters. I thought a lot about that when I was making the portraits for this work, these stark studio portraits. But in terms of the green, I think of influence as that it’s just all part of the soup. It’s like part of my visual language, it’s part of what I’ve studied or what I have spent my time looking at. When I look at the world photographically, I’m thinking about light and form, not thinking about color. In fact, I find color very distracting photographically. But the book was an opportunity to make an object, an experience for the viewer. For me, that’s where color can become really operative and instructive. The choice of green was to mirror the canopy in a grown-over forest. The kind of dark, dark green that you can encounter. How even if you look at your skin, it’s reflecting that green, it covers everything. The color was meant to reference the forest, but the curtain was meant to reference the stage, the performance, so that as you open the book, you understood you were coming into something of a performance. The studio portraits in this work that point directly to a history of performance.

JD: The book has three different kinds of photographs. I found landscape, documentary photography, and the studio portraits. I was especially interested in, well, I don’t want to say pulling back the curtain but—

KP: You have a good pun.

JD: Ha! But I was curious about that process, curious about your distance from the South and leaving Brooklyn, where you had been for ten years at that point.

KP: Thirteen years.

JD: You were living in Brooklyn for thirteen years, but leaving to photograph the Southern landscape, then coming back and doing the studio portraits in Brooklyn. How did that distance from the South affect the way that you then kind of crafted the earliest versions of the studio portraits?

KP: The concept for the studio portraits was always meant to be what I call a psychic space. So not real space, not real place. They were meant to represent the ideas in the mind. So they’re not situated in the South. I am so interested in place, and place geographically as much as place culturally. But for the studio portraits, well…I thought I was crazy for making them because I’m not that kind of photographer, right? But I really wanted to see them.

JD: And what is “that kind” of photographer?

KP: I work in the world. I always thought my job is to be in the world and make sense of it with the camera. I’ve always been taught that the world is more interesting than anything you could come up with in your own mind. And I believe that to a large extent. I really do. But I was struggling with the question of, how do I represent what’s in my mind? How do I represent my mental or psychic preoccupations if I’m not seeing it in the world? Or, if what I’m negotiating when I’m making work in the world are these thoughts in my mind. For this work, the thoughts were about vulnerability, about being alone out in the world, being alone and encountering someone in the forest or wherever. Those preoccupations color the way I move through space. They affect what I feel like I can accomplish in the world sometimes. How do I make pictures about that? So yeah, they needed to be built. I don’t think of them as Southern, and I don’t think of them as connected to the South or place. That’s expressly why they have a black endless space to them.

JD: When you open the Dark Waters book, the first image is The Medium (2017). It hints that it’s through her that we see the images, we enter the book through the medium. What is your interest in the medium as it relates to the oracle of Greek mythology?

KP: I don’t know if I’ve thought about it mythologically. I do think a lot about a sixth sense and intuition. I think it’s a very-close-to-true statement that every time I have ignored my sixth sense, I’ve gotten in trouble. One of the things we learn as we age is to trust that instinct to not fight it. Call it Spidey-sense, call it whatever you want. The medium is being able to hear yourself clearly.

JD: I was thinking about representations of women who’ve held power, like the medium. I am reminded of how women who’ve held power or owned property would be accused of witchcraft. I am wondering about the medium’s relationship to the witch as having some extra, intuitive powers.

KP: Yeah, women’s power has always been vilified by men in whatever way, and sometimes also by women who can’t escape a patriarchal mindset. It’s not surprising that we are groomed to move away from those powers. It makes perfect sense that, in this society, this wouldn’t be encouraged or broadly accepted. That it’s not frou-frou ideas, but something real…I mean, that’s cynical. And I don’t mean to be cynical. I just think we live in a society that disempowers women in all kinds of ways.

JD: Yeah, that could be perceived as cynical. But when I hear this, I just feel that you’re speaking the truth. Thinking about women artists, the success of women artists and how that can be played as troublesome to the patriarchy. There is a connection between the troublesome women in the murder ballads referenced in this body of work and you as an artist. You are generative, creating voice. You’re getting ready for a large exhibition at The Momentary at Crystal Bridges and you’re collaborating with musicians. How is that going?

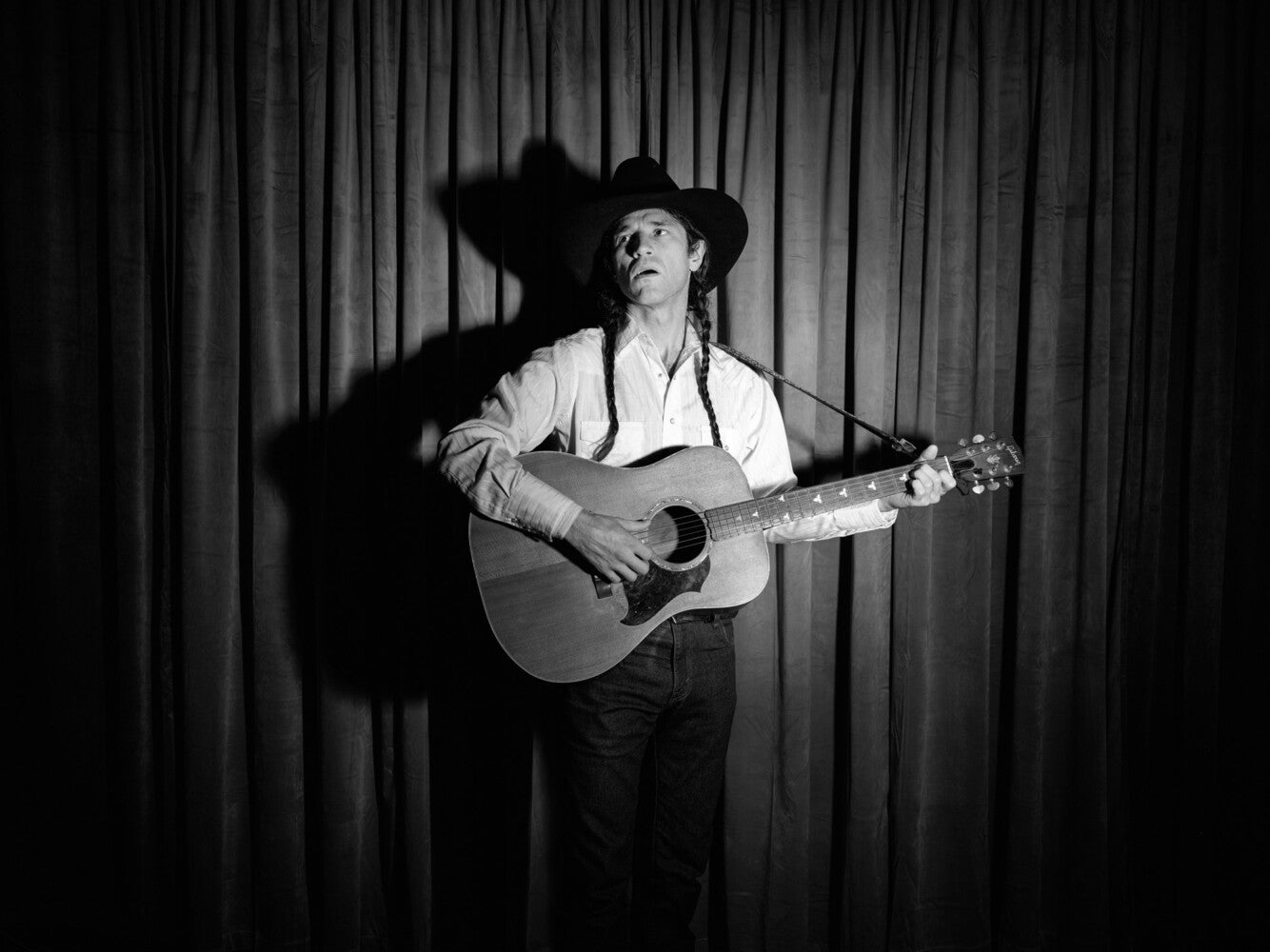

KP: It’s so fun! I’m collaborating with Heather McIntosh, someone we both know from Athens, Georgia, who now is living in LA doing all kinds of amazing things. I’m trying to think of when I started this conversation with her… I knew The Momentary would be the place just because it is an institution that’s so interested in multimedia experiences. I thought, well, I already have a video component—it’s these men singing murder ballads. And that’s meant to stick in your mind when you move through the photographs. But I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting to give women voice and to build some soundtrack built entirely of women’s voices—and bodies, as it turns out. What I’ve always known about Heather since we worked in Dixie Blood Mustache a million years ago was that she’s interested in thinking outside of the box with experimental musical ideas. She’s hired in some amazing singers and has just done some interesting things rhythmically with clapping and humming and breathing. I think we are trying to create something that might blow by like the wind. It will move directionally through the space—it will be gone just as soon as it was there. It’s a new way of thinking about making, it’s a new way of accompanying the photographs that I’m excited and nervous about. I want to get it right.

JD: I’m thinking of other photographers from the past that have had so-called soundtracks, someone like Nan Goldin. Are there other photographers that you’re thinking about as you approach the sonic component?

KP: No, I’m not. I feel rudderless in this idea. Nan, whose work I really admire, was using Bjork and, before that, New Wave. Songs that were of a generation, songs that had narrative component to them that you knew, that you could sing. I’m creating something much more abstract. I wouldn’t even call it musical, although it has a musicality, I suppose. It’s more of an abstract sound environment, like this ephemeral wave just washed over you and left.

JD: You spoke previously about photographing these dark, lush landscapes so that every detail is in focus and discernable. It’s not just a technical prowess, it’s from a drive to see into the distance, to know what’s behind the forest canopy, behind the curtain. To be safe. To have a map.

KP: Yeah, at the end of the day, I would like to think I’m kind of a photographer’s photographer. I’m interested in describing the world. I’m interested in how tools affect the way I can see the world. When I came to photograph the South, I wanted to work in this lower tonal range, to talk about darkness, talk about the effect of darkness. And I didn’t want it to be obscured. So I had to change my tools, to use tools that allowed me to work faster, to be more agile, and to describe darkness. I’m not interested in describing the South as this hazy, obscured place. I think the most mysterious thing is a well-described place. That’s where I enter the landscape, not trying to be mysterious through omission, but to be mysterious—if that’s the right word—through description.

JD: It also makes me think again of different outcomes. The history of the South has been told so frequently that way. By obscuring…or by omission.

KP: Especially photographically. And I can appreciate that history. But if I’m going to pull a chair up to the table of art history, what’s my contribution? It can’t be what she just said, right? This certainly felt like a space where I could contribute that felt different, that felt specific.

Truth Told Slant is on view at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta through August 11. Kristine Potter: Dark Waters is on view at the Momentary, Bentonville, AR through October 13.