Right Here

Right Now

We begin

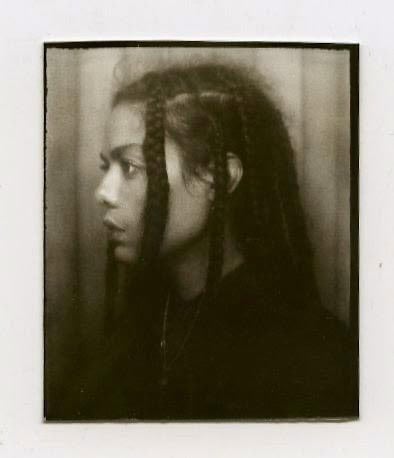

Erik Thurmond sings these words into a microphone, standing under a spotlight among a large crowd. He is performing under his new project Pasquale, wearing a blazer and sunglasses inside, both oversized. I watch this in the form of an iPhone video shared by the artist. His movements are molten, abstracted by flashing lights and the camera’s inability to maintain focus. This is recent performance at the music venue 529. It’s a mesmerizing effect, while also notable to see something like this homegrown in Atlanta.

Pasquale is Thurmond’s Pop music alias, a new vehicle for the artist known primarily for performance art you may find in a gallery or theater rather than a grimy music venue. This isn’t to assume that previous work was boring, stoic, or institutional; Thurmond’s work has always had a sense of humor, a pomp, or joy in the act of performing. Perhaps the most relevant precursor is Pandemia, a band formed with fellow Atlanta artists Sara Santamaria and Parks Miller during the pandemic. During a short but prolific run, the band cultivated an odd ball reputation through a series of memorable performances and a trail of various band ephemera, including lyrics, demos, and a game. The image that sticks in my mind is the event in which the band performs in revealing swimwear behind the former Value Village on Moreland. Thurmond, in an electric yellow brief, climbs on top of a car and smashes it, followed by a crowd of speedo clad imitators. The audience cheers on.

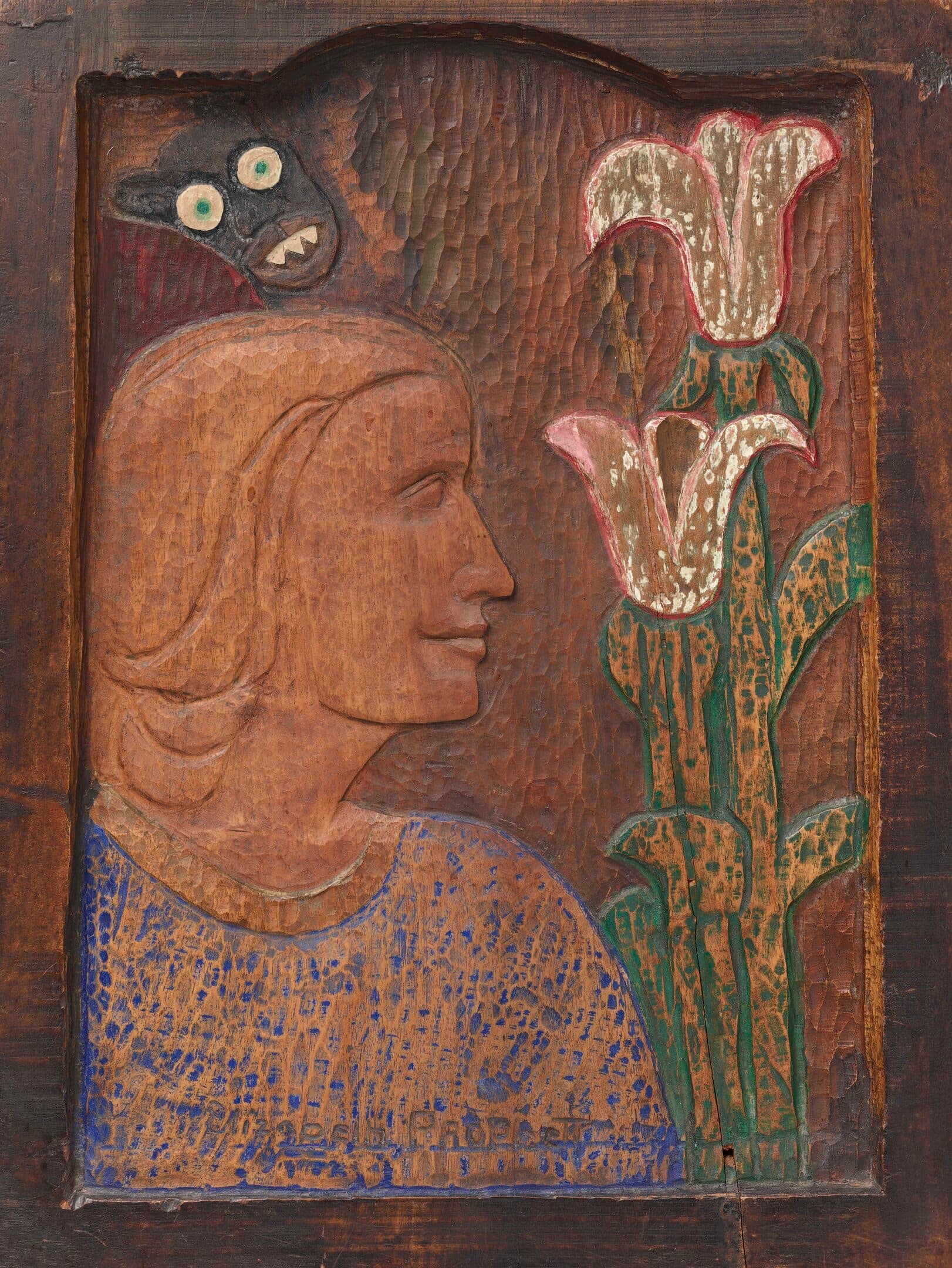

So perhaps Pasquale is Thurmond’s solo breakout moment. He still collaborates with Miller, who brings a lite metallic weight to Pasquale’s shiny melodies. When planning our interview, I ask whether we should take the popstar on a major label route and do a predetermined PR activity together, something a little outrageous that informs the artist’s current work. Pasquale responds with a dense list of things he’s thinking about (Mysticism! Nature! The Divine!), followed by, “Any fun places come to mind?” In the end, we decide on a humble studio visit, in an old garage transformed into a black box rehearsal space.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Jackson Markovic: One interesting detail that I noticed when viewing your performances was the making of the invisible visible, in particular the idea of the stage or the venue.

Pasquale: That move was really intentional, because I’m interested in the audience having more agency than in contemporary performance spaces. I’m wanting my work to be more accessible and thinking about how pop music has this accessibility that contemporary dance and contemporary performance do not. So, I’m using this vehicle of pop music or this kind of Pop star character to bring a lot of the same themes that I was thinking about through dance or through performance into a space or into spaces where people are drinking, are partying, can move around, can dance, can sing along.

I recently performed in a space called Pageant in New York that is very much a dance space and returning to that context was very meaningful in understanding the work. But I think specifically in Atlanta, music venues are so much more available and there’s so much more of an infrastructure for that than there is performance. It’s interesting too because theater spaces and dance studios or dance stages are my first creative language. I think that’s something that marks my work as different [from] other artists that are showing in music venues, because I’m thinking about the trajectory of my body in the space, or the lines of the space, the way that one might think about a ballet piece, but again, it’s music.

JM: I’ve also been thinking about that move towards more performance venues, in relation to the work of José Esteban Muñoz and his theories of ephemera in relationship to performance. He said, “Instead of being clearly available as visible evidence, queerness has existed as innuendo, gossip, fleeting moments, and performances that are meant to be interacted with by those within this epistemological sphere, while evaporating at the touch of those who would eliminate queer possibility.” I’m curious about that quote because performance is explicitly mentioned. Have you noticed the elimination of queer possibility as you traverse these different spaces?

P: I think there’s an interesting tension between me and the recordings or documentation of what I do. And some of that has to do with my own strategies, or lack thereof, where I get consumed by what I’m about to be performing and things like how it’s documented become these like last minute details that I forget to tend to. I think a lot of the power of the work that I’m doing is felt body to body by the people that witness it. And I often get feedback that means a lot to me from audience members where they say, “Watching you perform helps me understand the possibilities of my body, and seeing you liberated enough to sing and move the way that you do up there empowers me as an audience member to try new things with my body, or to at least recognize the potential there.”

JM: That’s something that I find really inspiring in your work. Having studied some performances, things get stuck in my head. I want to emphasize, you said, giving the audience agency and being able to process it in their own time, I thought that was a strong detail in your work.

P: I’m glad to hear that there’s melodies stuck in your head, because I think that’s often how I’m working: What’s the earworm? Or, what’s catchy, and again, deciding that it’s pop, you know what I mean? It’s experimental, but it’s pop. That makes me excited.

JM: Pop music is often so nebulous and undefined. Do you have a working definition for pop music?

P: I am currently reading this book called A Dialectic of Pop [by Agnès Gayraud] and the way that the writer positions it is very broad. So sometimes I say I’m making pop music and friends will say, “Well, I don’t think it’s Pop.” I think that the way that this book is helping me is because it’s music that is popular. I think people sometimes associate it with like, the kind of Britney Spears, Lady Gaga, NSYNC, Backstreet Boys, but those kinds of definitions start to really quickly slip apart because Top 40 music, especially now, includes rap, hip hop, R&B, and rock, and those kinds of trends move and shift through time. I think that there’s a connection between pop and folk music, or obviously pop and rock. It’s music that can touch on big topics, or reach people, even if not lyrically, instead through sound or through rhythm, melodies, motifs.

JM: With recorded media, and especially music, I was thinking earlier about how it’s perhaps unusual to see a movie ten times, but to hear a song ten times is not a lot. It’s pretty normal. Especially pop music, which often has structures or a chorus that repeats. You said that empowers your audience because they’re able to rehearse or know the words. I’m thinking about this transition to a file recording-based media.

P: It moves through my work in lots of different ways. I think there’s always a desire to blow some of the music up into more expansive ambient spaces. For the time being, it’s all very rhythm dance based. My friend Alexa, who runs this space Pageant that I got to perform in, said something about how you can tell a dancer made this music because the sensibility of the beat is something that a dancer would want to dance to. I know when something’s working in a recording or in a song because it’s calling my body to want to dance to it. That’s like one space that repetition is happening, in the repetitive rhythm of a song.

Pop structures, like you said, often repeat choruses or bridges or even verses. The lyrics might be different, but the melody might be the same, and there’s a way in which that pulls a listener into a space of comfort. I know lots of people that re-watch movies over and over again. Maybe not lots of people, but I feel like that’s a type of person who’s deeply comforted by just putting on Mean Girls or whatever and being like, “I’m gonna watch Mean Girls again tonight.” I’m not that way with film. I’ll watch some of my favorites again as sort of like a research thing, but there’s so many movies that I want to see that I don’t ever really go back. But I can [do] an entire workout to one song over and over again.

I got really into mysticism during the pandemic, and I would go out into this tennis court in my parent’s suburban neighborhood. I would approximate what I learned to be the practices of whirling dervishes, as in, spinning over and over again as a way to turn yourself into a doorway to contact the divine. Repetition is also something I think about choreographically in work where there’s moments where a gesture is repeated or a posture is repeated. But because it’s happening through time, even though the form is the same, it’s starting to take on new meaning or it becomes something different because both me and the witness have shifted in time.

JM: You mentioned mysticism, I immediately thought of Choire Sicha, the writer who wrote the press release for Perfume Genius’ album, No Shape. I have a quote here because it felt very kindred to your current project. “God is all around actually and some of these songs are about being equal and some are about the witchcraft of believing. This is church music the same way Prince’s Black Album is—too dirty. It’s femme art pop the way Kate Bush’s The Dreaming is—too scary.” What strikes me about that album in particular, and the ones mentioned, is how the songs seem to transcend their material boundaries as an MP3 or however we may listen to them. Do you have any references that you would like to share that feel relevant to the work?

P: In terms of mysticism, I spent time with Thomas Merton or St John of the Cross, Teresa of Ávila, mystic Islamic poets like Rumi or Hafiz. I think in terms of more direct influence to the work, those Islamic mystic poets. There’s an approach that they sometimes use where they’re writing poems, or in my case, I’m writing songs, that can simultaneously be about an earthly lover or God. That’s not always the valence that I use, but it is a through line where I’ll have an experience, I hook up with someone, or something happens romantically that feels like fodder for a song. And then in the process of writing it, I’m thinking about how it can also be a song about God.