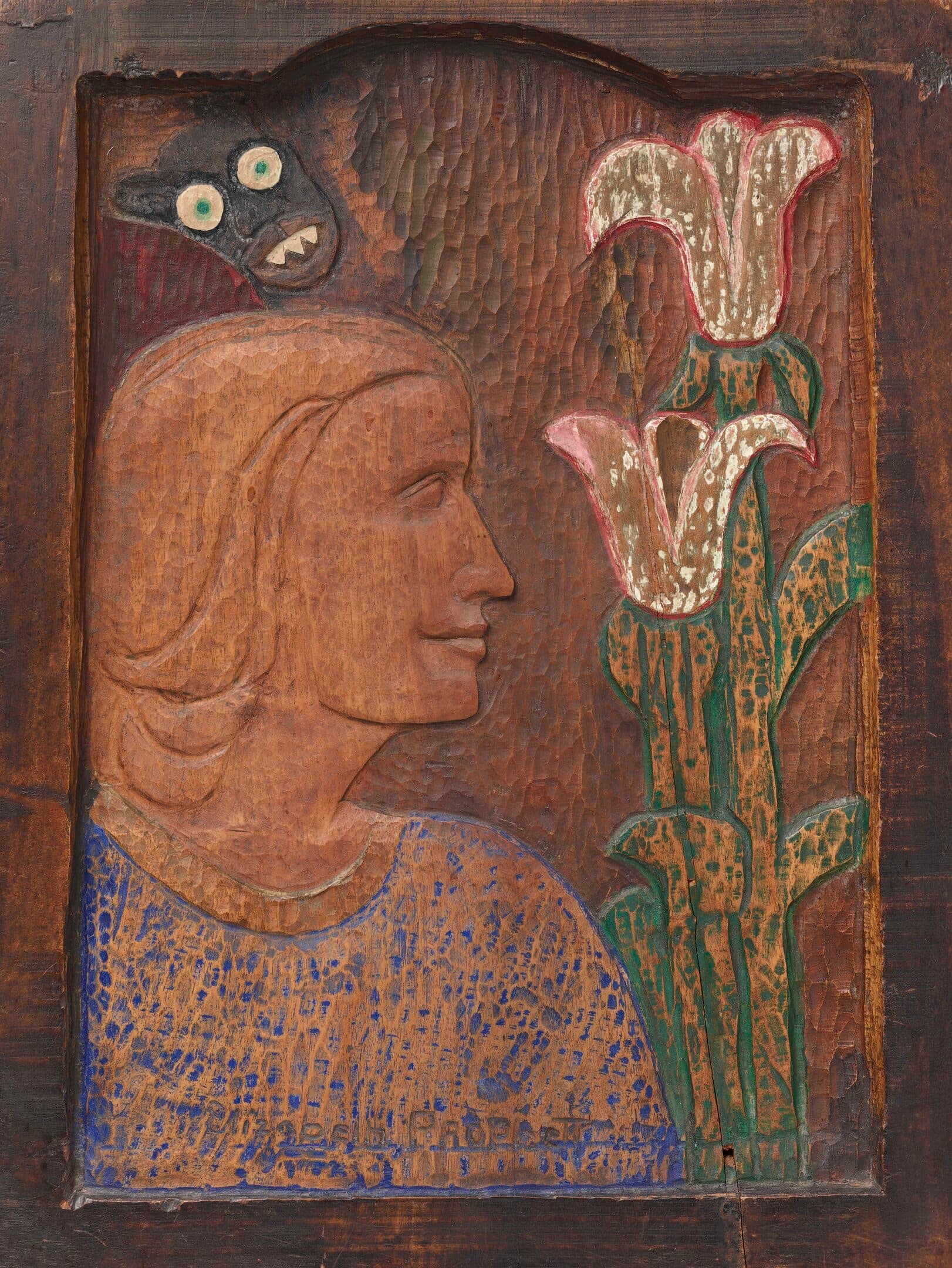

wood, plaster, found objects, photocopies, acrylic, wood glue, cotton string dyed with

goldenrod, 2022, 36 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of Earthen Clay.

Earthen Clay makes space for chance and transformation. He doesn’t pin things down. Wrangling together neon yarns, netting, twigs, pink drawings, and pages from quantum physics texts, his interdisciplinary practice generates a collaborative edge.

Clay grew up in an extremely religious family. Born in Anchorage, Alaska, and also raised in North Carolina, his orthodox upbringing forbid light-hearted activities and imaginative play common to many childhoods. At eighteen, he moved to Nashville to attend Watkins College of Art at Belmont University.

In Nashville, a friend introduced him to a rural Tennessee commune which sustains a rare queer and trans community. Soon, he joined that place in the woods. Though he didn’t come to realize his queer identity until his mid to late 20’s, living there was crucial in allowing him to see himself.

Now, Clay resides in the Northeast, pursuing his MFA at Yale University. Clay wonders: What does it mean to have a connection to a place that you aren’t in and how do you take that with you? He asked friends on the mountain to send him materials, building feedback between two grounds.

wood, plaster, found objects, photocopies, acrylic, wood glue, cotton string dyed with

goldenrod, 2022, 36 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of Earthen Clay.

Since the start of 2023, a historic wave of legislation has targeted LGBTQ rights, education and healthcare in particular. Despite studies which show that gender-affirming care can be life-saving for trans youth, the new laws attempt to ban access. There has also been a heavy focus on regulating curriculum in public schools, which restricts conversations around gender identity and sexuality.

I talked with Clay about speaking out against the laws in his home state of Tennessee, his work, and the impact of creating portals for glimmering, joyful euphoria in the face of oppressive forces.

Blair LeBlanc: The first thing I want to touch on is the fundraiser that was started this summer by Mutual Aid Babes (a mutual aid fund for and by queer and trans rural organizers in Middle Tennessee). Can you tell me more about how you got involved?

Earthen Clay: The fundraiser was organized earlier this year with a sense of urgency. I felt like, this is what I can do. Push the fundraiser online. And it quickly reached its goal. The funds can be accessed without [a] say on who can get them or why. Without deciding one need is more legitimate than another, you know? That feels important.

In Tennessee, it’s already challenging to get any kind of healthcare. When I was first accessing hormones, it was hard to find them consistently. And now, it’s just becoming more so.

A friend of mine was constantly posting every day like twenty or thirty slides on Instagram about the bills, sharing phone numbers, and live updates. They were going to the capital and the hearings and testifying. That was such a powerful moment. I was watching the video of my friends getting up in front of the legislature. And I just felt like, I want to be there with them. But I’m at Yale in Connecticut, so I’ve been trying to think about what I can do. It’s wearing on people, but still there’s a sense of, “They can’t have the South.”

BL: I hear that, I’m always interested to know about other queer people’s perspective growing up in the South. It’s a unique place in that there’s a big conservative population, but also so much space for alternative communities to form.

EC: It’s much more diverse than the popular sense of the South is. It gets reduced to the loudest conservative, Republican voices. I grew up in a really religious family. It was like no dancing, no card playing, no secular music. It was an extreme side of an oppressive religious upbringing.

I didn’t kind of come to realize that I was queer until mid, late 20s. And I was kind of like one of the Covid transitioners. That being said, it doesn’t mean that I wasn’t queer. I had just deeply internalized so much that it was hard to access.

So, when I was eighteen, I moved to Nashville to go to Watkins [College of Art at Belmont University]. And when I arrived, I met my friend CA, who took me to a rural Tennessee commune. And that’s where, even though it kind of took me ten years, I was able to see myself. Being there was so crucial.

It feels so rare to find a place with so many queer people and trans people. At the mountain, you don’t pay rent. But you contribute, still contribute in a number of ways. The community where I stayed was centered around dumpster diving, [anarchy], and consent-based decision making. We were particularly interested in political action.

BL: I feel like I think about found objects and your new work when you mention dumpster diving. I’m really interested in them. One is an almost figurative sculpture, lime green, composed of branches, a hoola hoop, there’s one shoed foot and a drawing. And it has an enchanting quality. In some ways the piece looks like a mythical creature pulled from a forest. There’s playfulness there.

EC: So, I definitely resonate with all of what you’re saying. And it starts from going and finding material or being given material. Last year my friend Susie, she’s at VCU now in the Painting program, but was on the mountain last year. She collected stuff from the communal spaces and sent me all these boxes. So then, when I was making that work last November, I could lift something out and see, this is already doing something. The work then becomes a collaboration.

I’m thinking about: Where is choice coming in? I’m not trying to have control over these things. And it feels exciting to not have that. The object already has some kind of character. It already has a history and a context. So, then I’m responding to that, instead of starting with, “I have an idea and then this is going to happen.”

Someone brought this up recently, that they saw the material as discarded. As in the discarded object or a discarded identity. And I can see that, but for me, it’s more about the beauty and pleasure that are embedded in these things. These things that seem like they might not have that. So, it’s less about this thing being discarded and more about a devotion to this thing that has had another life. And will have even more after.

BL: The devotion to something that has had another life makes me think of how place shapes and changes one’s identity.

EC: I was definitely contending with that when I got here. It was part of why I was asking my friends to send me stuff from the mountain. I was thinking, ‘What does that mean to invoke another place in this institutional space that’s historically been seen as a neutral container.’ And thinking of how I can create a portal and open up space in between.

I want to connect these places, not replicate them. Like one thing I think about a lot is like high-heeled shoes left on the side of the trail or the sidewalk. When you see them the morning after. They are doing so much…to call to some other place and time and space.

BL: Yes, and energy. You mention clothing and high heels in a text-based piece. Could you tell me more about that?

EC: That piece was part of a larger writing that I did for a class, with a prompt on archives. So, it was coming from an experience I had at the mountain.

It was the work week before the gathering and the shitter needed to be dug out so that it could be used for hundreds of people. There’s so much physical labor there and some of it is really gnarly. But people put on music and it becomes this glamorous thing. It becomes almost a Sub/Dom thing of, ‘I’m gonna be doing this thing for you.’ Like people are doing this thing so it goes fast. Then people are having fun, then more people want to join.

So, I was thinking about that in the writing and the flow of it. The people, material, land, critters, metabolic processes. Wanting them all to flow together. The separation being less apparent.

In another piece, I collaged pages from a Karen Barad text about matter, feeling, and being embodied. There, I’m using the physical text as material.

So, I think about language a lot and how it’s complicated. It can be violent in its reductiveness, in its pinning something down. But it can also be open and allow for other things to come in.

BL: I can see that simultaneity. And so now you’re studying for your MFA and at the end of the two-year program, you’ll have a thesis exhibition. What are the current themes and ideas that might culminate in that show?

EC: The primary question I’m coming up against is, ‘What is that physical interdependence?’ I’ve been making a lot of figurative work. Some attach to the wall, some are free standing in the space, some lean against the wall. But I’m not making them with a plan. I start with the material and then think what they are, and then how do they exist together. And that sequence is important, that [I’m] finding out how they exist after they’ve already started to come into being.