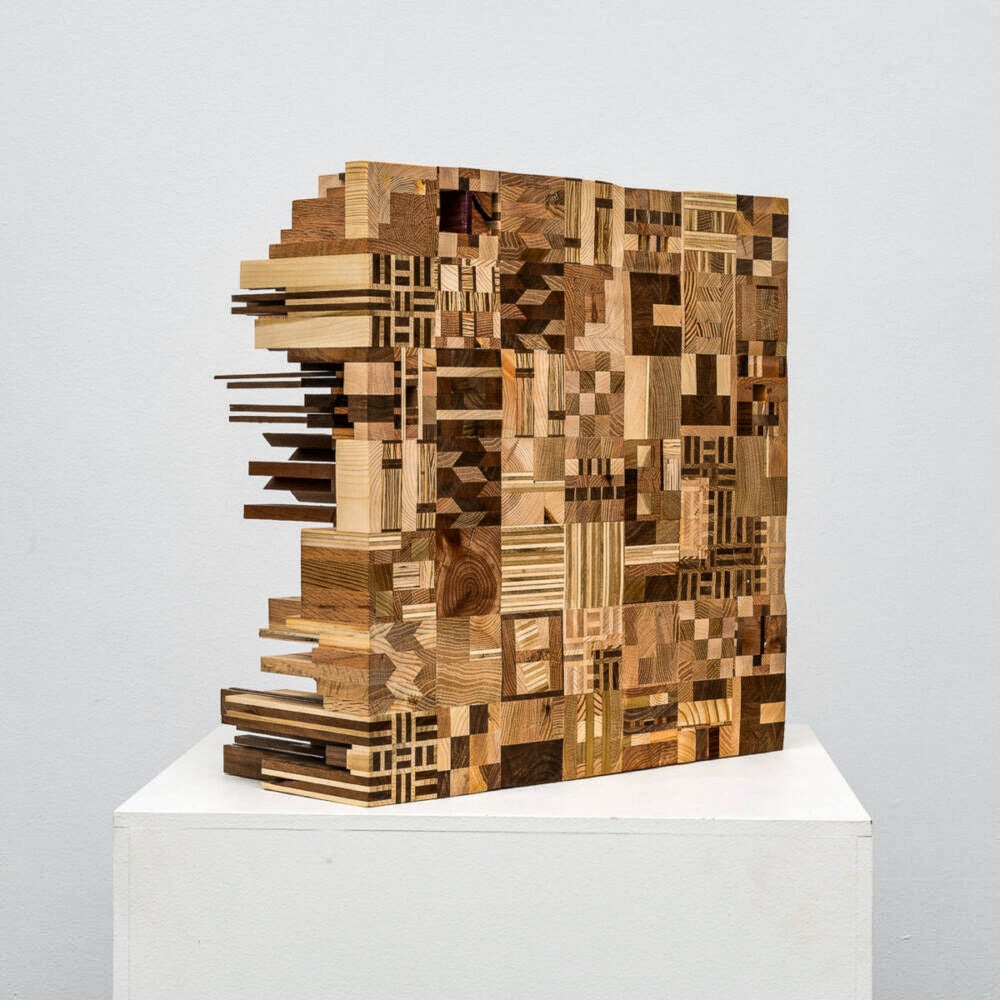

The African diaspora’s long history of pattern and printmaking is overlooked and underappreciated within galleries and art education. Today, there is a significant emerging artist with a culturally hybrid lens who intends to rectify this omission. Ato Ribeiro, a multidisciplinary artist born in Pennsylvania, raised in Ghana, and educated in the heart of Atlanta, builds a diasporic bridge he is uniquely suited to construct. Ribeiro’s understanding of the significance of storytelling via patternmaking as an art form has fueled his series of wooden textiles, wherein he utilizes discarded wood to address the treatment of the Black community and centers the Adinkra symbol of Sankofa, meaning “go and retrieve it.” I sat down with Ato to explore his life and works.

Burnaway is excited to present Ato Ribeiro’s work at the New Art Dealer’s Alliance fair in Miami, on December 5-9th, 2023, at Ice Palace Studios.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Amina Daugherty: Ato, you were born in Philadelphia and raised in Ghana. Something that stood out to me about your work is your desire to represent what you call a, “contemporary sense of cultural hybridity.” Could you elaborate on what that means in the context of your work?

Ato Ribeiro: When it comes to art, we all have our entry points and we all have our origin stories. I think that all of our origin stories are very international. We embody the experiences of the traveled interactions that we possess and who we integrate with, who we associate with, the places that we go. This understanding has opened up ways for me to see [our shared experiences], [as a form of] quilting.

AD: You have described your work as a bridge between your West African and African American identities. How did you go about finding the connection points between these two parts of yourself within your pieces?

AR: My work largely deals with unpacking my upbringing. In Ghana, I grew up surrounded by African American iconography like The Wiz, and I grew up visiting the Dubois Center near my home. But these things didn’t have as much significance to me until I came to America and explored them more in the context of the community. I felt like in both worlds, people often did not understand why a person, piece, or movie was significant to the other community, which made me feel alone in my hyper-awareness. So, in my pieces, I have the opportunity to slowly work through these connections and relate elements of our shared histories.

AD: How did you develop your process of turning discarded wood into elaborate finished works of art and how has that process evolved?

AR: My process is very different than it was in the beginning, but there are a lot of throughlines. When I started, I was a student at the Atlanta University Consortium (AUC). While I went to Morehouse, as an art major I spent a lot of my time working under Spelman’s Frank Toby Martin, an amazing professor. I remember during my directed study in sculpture, I vented to him about how I thought Georgia State had better facilities than us, and he said “Yo, I’m making museum shows with the same equipment you’re using. You have no excuse.” So that made me realize that it wasn’t the materials that were limiting—it was my mindset. Learning how to work with what I perceived as less and not making any excuses was huge. That’s when I became fascinated with discarded wood, it allowed me to change what was seen as nothing into something greater. In the beginning, I used a lot of free magnolia seeds and Banksia pods I found around the campus and in the West End.

When I got to grad school, I had a job as a shop tech at Cranbrook in their woodworking facility and fabrication studios. I had the space and time to get familiar with table saws and chops saws there. As I got more comfortable, I started noticing how much waste would come from other students after they finished working on a project. So, I just started collecting them. As I got better at it, I also had a chance to see all of the cool pieces that other people were working on and built confidence in working with the scrap materials that came from them. I find it incredible that all of this came out of necessity and evolved during a part-time gig.

AD: Patternmaking has long been an integral part of communication and storytelling within the African Diaspora. We have the use of patterns in braids as maps to freedom and African Fractals representing the hierarchy of a community. Your work in particular honors this tradition through the use of Ghanaian Kente Cloth and African American Quilts. What is most impactful to you about continuing the tradition of pattern making and what kinds of narratives do the patterns that you create carry in them?

AR: My dad is a mathematician, so pattern making feels extremely natural to me. By the time I got to grad school for printmaking, I realized that it essentially boils down to the patterns of communication used to relay messages to the public. Like how a king has a certain pattern of speech, and his bishops are the only people who know how to decipher it, so they can pass the messages along. Or how on social media, knowing how to access certain speech patterns through trends determines who has reach and impact and who doesn’t. Thinking about it in that sense, I became fascinated by how patterns and systems of documentation highlight some histories and omit others. In my studies, I became very frustrated by the realization that printing history acknowledges very Eurocentric histories like lithography, but omits virtually all else. Any student in America would assume that Africa never participated in the history of printmaking, and thus never participated in, nor contributed to, this significant method of communication. But we’ve been participating in this from the beginning. We’ve always used textiles to share stories, such as strip weaving practices, Adinkra symbology, and African American quilting. We have always found ways to re-contextualize materials that deal with how the rest of the world communicates with us, and how we communicate with it. So, I believe it is my job is to spend time making the world remember our significant contributions to this field by reimagining traditional mediums.

AD: Though much of your work celebrates the patterns in Kente Cloths and quilting, in those pieces I also pick up on the shapes and movement of the city, different skin tones of the diaspora in the colors of the wood, and even the connection between Black people and the land. At the same time, another viewer may not pick up on these things. What is your experience knowing that the narrative of your art is colored by the specific experience with race and ethnicity that each viewer has?

AR: I want to preface this by saying that no response to the work is “wrong”. For example, there are a lot of associations with architecture reflected in the work that you don’t have to be African American or of the Diaspora to appreciate. But if you can understand the modular nature of the works, and if you can understand the materiality of the pieces, you can get more out of them. If you can understand why the type of wood used or the shading is significant to the history, your experience will be robust. But the beauty of art often is being able to project your own life experiences and cultural competencies onto it. That’s what makes it communal and communicative. My goal is to make viewers appreciate the art so much that they are willing to do the research and learn more to understand why the choices made are significant and powerful, stepping outside of their cultural biases and making room for new information.

AD: As someone uniquely suited to bridge gaps between Africans and African Americans with your art due to your background, what are ways that artists can accomplish this in a respectful, thoughtful, and authentic way?

AR: Listening is the most important thing you can do to create art that successfully bridges gaps between communities. No matter who you are, no matter how much you think you know about each culture, the best practice sometimes is to shut up and open your ears. Because ultimately, you are accountable to each community to represent them well and fairly, and so the conclusions you draw and similarities you point out will have consequences. If you can take the time to step outside of your own biases and experiences and listen to other members of the Diaspora, you can create art that has the right kind of impact. My other advice is to give things a try and know that sometimes you will fail. No matter how hard you listen, something can fall through the cracks. But if you are intentional and diligent, your efforts will be appreciated.

AD: You seem to have made your way through several states including Vermont, Maine, Michigan, and now Georgia. Where is somewhere that you found inspiration that you did not expect?

AR: Yes, there have been a few places that have had that effect on me—New Mexico and Arizona immediately come to mind. They both have this odd, everything-looks-photoshopped-and-very-surreal quality to them. But visiting as a Black man, there is this association with histories outside of your own that you’re never told about but that you can feel clear connections with, histories that may feel so familiar. In New Mexico in particular, when I went through the pueblos and experienced different rituals, I noticed similarities in real time without understanding how to access them fully. I want to continue to explore those connections through more of the Southern United States. I would love my work to be a bridge-builder between these histories.

AD: Where do you see yourself heading next?

AR: First and foremost, I would like to go back and recharge in Ghana. I would love to find a way to have friends here come to Ghana to see that it is a remarkable place. I would also love to be able to go to Haiti. I’ve never been, but my two older brothers have. My mother and her siblings were born there. Their mother is Haitian, and my grandfather started an airline out there, so there is a lot of family history out in Haiti, but I was not old enough to experience that. I’m glad actually, because it is on a pedestal in my memory. There are a lot of places in the Southern Hemisphere that I would love to experience…but you know, money… so, baby steps.

Burnaway is excited to announce our solo presentation of work by Atlanta-based artist, Ato Ribeiro at NADA Miami, 2023! Come see us Tuesday, December 5th through Saturday, December 9th, 2023 at Ice Palace Studios, Miami.

Ato Ribeiro (b. 1989) is a multidisciplinary artist working in a variety of media including sculptural installation, drawing and printmaking. He was born in Philadelphia, PA and spent the formative years of his life in Accra, Ghana. He is currently serving as a 2022/2023 MOCA GA Fellow, was the 2017 Mercedes-Benz Financial Services Emerging Artist Award recipient, Artist in Resident at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, Germany, and received Fellowships at Vermont Studio Center in Johnson, VT and Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture in Madison, ME. He earned his B.A. from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, and his M.F.A. in Print Media from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.