Antonio Darden’s work often looks comical, pulling from contemporary internet culture or media, Spongebob to C-Murder, but a complex and heartfelt energy shines through. Humor is employed to mask a serious confrontation with reality in all its tragic absurdity. Darden hopes to reach out, connect, and help others. He celebrates his loved ones, carrying with him their legacies and outlooks. Darden’s work is some of the most beautiful and gut-wrenching that I have come across in recent years. Together we discussed cars, grief, hope, religion, and the affective nature of music and writing that serve as undercurrents in his work.

Noah Reyes: You reference a lot of car culture in your work. Can you talk about that connection and how that came about?

Antonio Darden: When I think of a car guy, I just think of some dumb, easy, fit, dirty white T-shirt guy. But, it’s just something that was ingrained in my DNA. I come from a long line, at least on my father’s side, of people who built hot rods, people who raced, people who collect their cars. In my hometown, it goes hand in hand with the last name Darden.

What’s nice is like there’s a shared enthusiastic trade amongst the cousins now, it’s like our car is always kept clean. It’s always custom. And so that’s just a piece that I kind of have grown up with. Me and my brother, we collected hot wheels and we played what we called “little cars”, which was a world that we created with the cars that we had. And, it’s just something that my dad taught me, He taught me how to, of course, like change your spare, but he taught me how to change my oil, he taught me how to do a basic tune up, plugs, wires, filters, stuff like that, just so I wouldn’t have to spend the money.

“I think humor is like the crux of its human existence.”

NR: Your work resists a singular style and is quite eclectic. Can you tell me a little bit more about your process in the studio?

AD: I wish I had a studio practice. [laughs] What is that? I’m kind of an assemblage artist at heart. I know that sounds pretty stereotypical. I started practicing this [way] because I would become paralyzed by not being able to create because I don’t have what I need. I collect so much materials and just have all this crazy stuff in my studio, I just started walking around and looking at my scrap bins, looking at little tchotchkes that I saved. I know that paints a picture that I’m a cat lady, but I need some kind of adventure.

I had a mentor [who said], ‘you don’t need a studio practice. Like, why do you need a studio practice?’ I kind of mourn not having that ability to experiment in the process. And so maybe that’s kind of why I have turned to performance lately and even experimentation.

The work that’s hanging outside in the gallery here, I hung for a studio visit. And then a week later I had a party. And so just sitting here for a week, it gave me an ability to kind of play around with it.

NR: How do you think about performance and the role of the performer?

AD: For my performance Last Song (2024), I was dressed up as a cowboy, and there was a soundtrack. It was like I was standing behind a scrim and the back light came on, right? And then I was standing there just like a 90s talk show. And then I walked through these saloon doors that I created on the other side of this floating wall that were like angel wings. I had a mullet on, a cowboy hat, and then I kind of drunk danced to Down for My N’s (1999) by C-Murder around the audience. And that’s all I did, right?

Leading up to it, I was afraid that I would smile while I was performing. I had a studio visit with an artist, Ana Pi, and she made me practice and we practiced together. And so every night I started practicing. And when I was with her, I kept like kind of scrunching my mouth. I trying to look mean like I used to do when I was in the club, back when we used to throw bows like it was a mosh pit. Out of fear, you just don’t wanna be messed with. So she kept telling me, ‘No, straight, no. Don’t do that.’ I didn’t wanna smile.

Right before the performance happened, I don’t know who was performing really, because it wasn’t me. I brought myself together and I went out there and I performed. I was going around the crowd, and then there was one part where I started Crip Walking. After the performance was over I took the cowboy hat off and the wig and hung it on a hook that was already lit. I went and I got this old wooden chair on the backside of the saloon doors on the above the table. On the table was a pair of thick black frame glasses and a long dangly earring. I still had a wig cap on and some thick ski glasses. I took off the ski glasses and I had like this fake piercing on my eyebrow, fake piercing on my lip and then I put the long dangly earring on. I sat in the rest of that [critique] as Arthur Jafa.

There were people crying during the performance. And as I sat there, I stayed in that moment. I stayed completely shut off from everybody. And so people were crying because they didn’t have access to me. I had cut them out. And so I sat there deadpan.

I realized that while I was performing this one time, that was the first time in my life that I wasn’t performing, man. And so I have spent every waking hour and probably while I was sleep too, performing, trying to be funny, trying to be non-threatening, always. That’s what people expected. That’s what I’m trying to get through in writing now, how there’s this expectation that I created with my work, you know?

When people see me dancing to this song by C-Murder, they think that I’m working through something, but really the song is about them. This [character] is who I’ve been calling Funtonio. [The viewers] didn’t have access to Funtonio and they didn’t know what to do with that. I sat there and I just loved it. If I had a cigarette, I would have smoked it because, it was in this moment I was free to be pissed off—I wasn’t vulnerable.

I try to live that life that if somebody is going through something that I’ve gone through, then I’m here to help. I want to be that person, but for that one moment, I was like, dang, this is what it feels like to be completely shut off from everybody else. I just felt so alive. And I stayed there in that. Nobody spoke for like five minutes almost, because they were still afraid.

NR: I’d like to talk about humor, because it kind of weaves itself throughout your work. But I think it never detracts from how serious the subject matter you’re addressing. How do you navigate using humor in your practice to address your subject matters?

AD: I think humor is like the crux of its human existence. With everything that’s going on in the world, in the United States, in all that’s being done day by day, we wake up with something new, crazy, and anxiety inducing. I want to be in that writer’s room. I want to be in that writer’s room because that’s got to be pure comedy. You know, it’s so absurd. A lot of it is the absurdity of how ridiculous our day-to-day stresses are. Our miscommunications and our inability to really see each other even though we like right in front of [one] other. It’s just all so strange. That’s how I process so much, there’s always something to laugh at.

It’s kind of a fault because like in very serious situations I’ll still be laughing, or if me and my wife have a disagreement, my go to is laughter. She says when I get anxious, I’ll start laughing. It’s kind of the beauty or a capsule that can pull you out of where you are. If you deep in the middle of grief, you can think about something that’s funny.

NR: Again, I think about your work RICO (2022), seeing you address the loss of your brother. It’s a very powerful and universal reality to confront, and I thought you did it in an unwavering way with dignity. It is very vulnerable and so how do you think about vulnerability in relation to your work?

AD: I mean, you probably heard me say this before, but nothing that we go through on planet Earth, while we are here is for ourselves. It is to make us into who we’re supposed to be but we also are here to help others. A lot of that comes in humility and facing our faults.

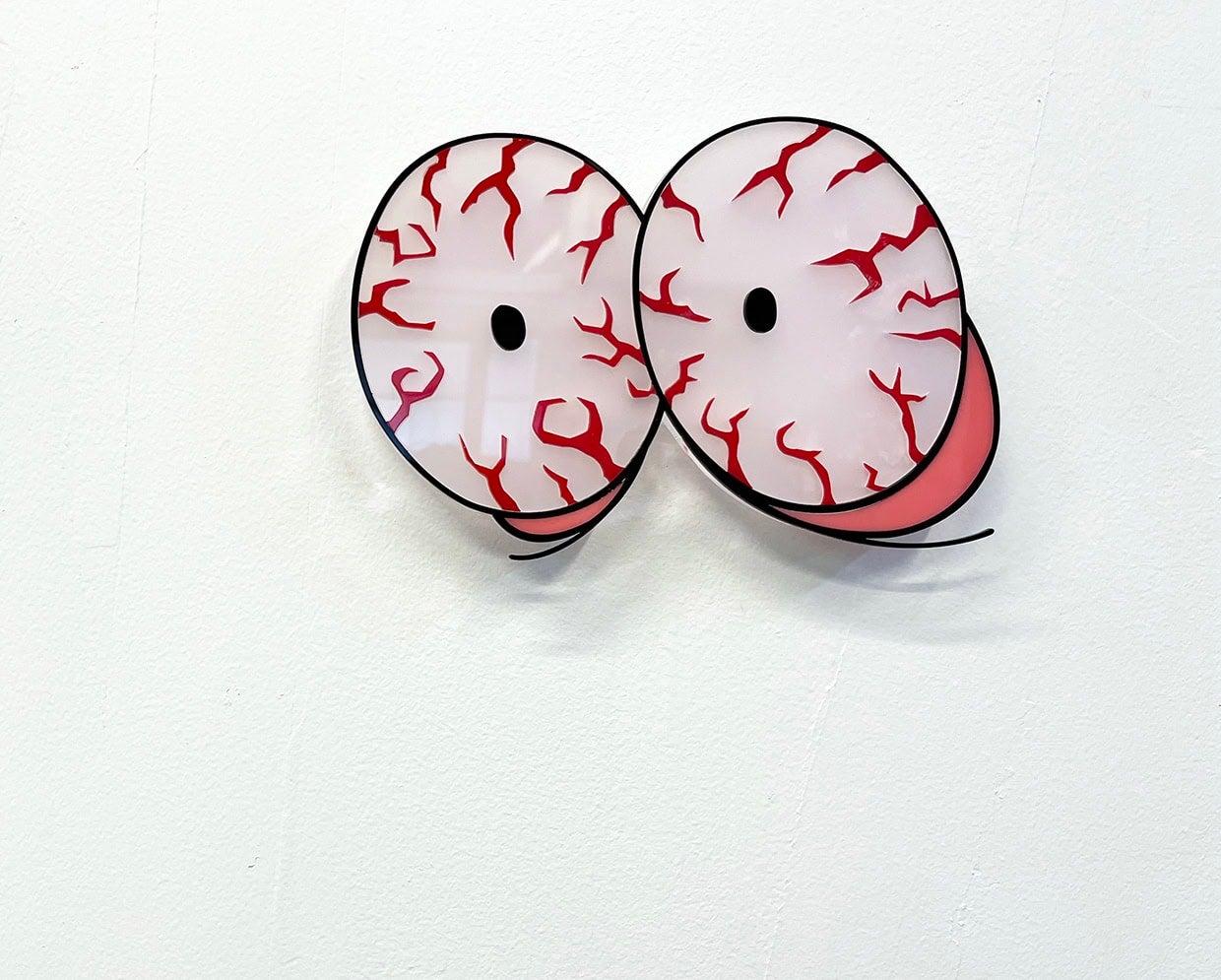

It’s like even in the statement I just sent for [EYES LIKE FIRE at Neue Welt]. It’s kind of rough around the edges like, I just want to show, I messed up. I got a lot of stuff going on, it was hard for me to get out of bed this morning. I know I’m not the only person. One text could just make me be sitting on the side of my bed for like three hours. I want to aid somebody, you know what I mean? That doesn’t come if I’m in a fortress, if I’m not letting people land or if I’m not being true to the stuff that I’m dealing with, because life on earth is tough. If I face it on my own, it’ll be impossible. And I understand that it takes community. and I guess that’s what I’m trying to create, maybe.

Burnaway is excited to continue Burnaway Artist Editions, a short run of art objects created by artists from the South and the Caribbean and intended for a broad scope of discerning collectors.

For our third Artist Edition, Atlanta-based artist Antonio Darden collaborated with Burnaway to create Untitled (Studio View), an isometric and introspective flag modeled after his studio. Inspired by LaShun Pace’s song “There’s a Leak in this Old Building”, the depicted studio is ‘leaking’.

Untitled (Studio View) is available for purchase in our shop.