Everything tells a story, and all stories are worth listening to in the end. Materials can conjure memories of personal experiences, of communities, and those who came before one. The colors and forms these materials take on create infinite points of connection for people to see themselves within another person’s story and image. This conjuring and creation of infinities is a sacred practice that self-proclaimed Southern polymath Anthony Suber is deeply familiar with in his work. We conversed at his studio, a rowhouse built in the 1800s that sits in the heart of Houston’s historically Black Third Ward. In a space that felt like a portal through time, Suber and I conversed about the nature of his artistic practice, his community-based work, and his hopes for the future.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Zahrah Butler: One of the many reasons why I feel compelled by your work is the way you blend concepts of time, space, and connections to one another. Your work strikes a very careful balance between providing just enough grounding in time, spaces, and people to feel as though you’re reaching inward to invoke your own ancestral narratives and lands, whilst connecting to a greater narrative about Southern Blackness. I’d like to know more about how you came into crafting this aspect of your artistic practice.

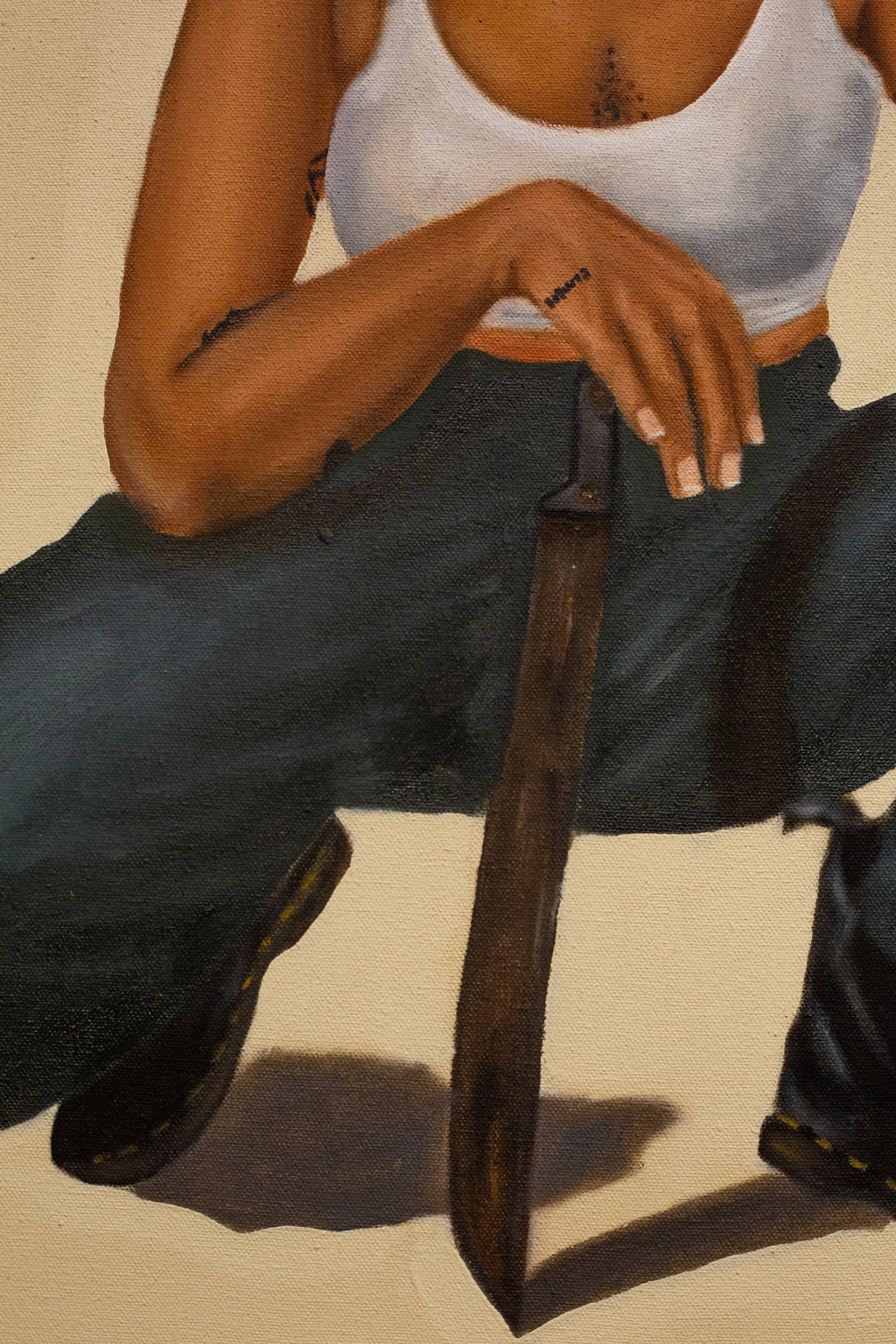

Anthony Suber: My father was an artist and my grandfather was a carpenter; I was always curious about their work. I would sit with my father and he would teach me whatever he knew about art or composition. Watching my grandfather helped develop my own curiosity for making things, crafting with my own hands. From the interest I developed in cosmology, I started to see a connection between being an artist and the sacred power that comes from creating. On the other hand, my grandmother was something of a family historian. I’ve spent time thinking about how I could tell the stories she collected in a way that connected to my contemporary experience of being a Black man in America. That led me to my artistic practice, where I embed pieces of my family’s stories and East Texas origins in what I depict. The way I use different materials, textures, and colors allows me to draw out other people’s stories and experiences, creating unique ways for them to connect to my work.

I’m also very interested in the idea of genre-bending—what happens when we take the established norms of art and challenge what people would typically expect? That’s how I started doing things like the wearable items, the masks, or even site-specific installations that pushed past just being a painter. I think reinventing myself in my art-making process allows me to reintroduce myself to the world and find better ways to bridge these stories, timelines, and connections.

ZB: I’m glad you brought up the masks! Your exploration of form feels most memorable for me in the way you depict the human body as a playground for abstraction. In particular, you investigate the abstraction of identity through masking, especially in the way your male figures tend to wear masks or lack facial features entirely. What causes you to constantly return to this idea of masking oneself?

AS: It’s a representation of who I have been and currently am, alongside the Black men in my family and community. Masking is a way that we craft ourselves in society, but the meaning and exploration of the masquerade can take on a lot of different forms. In a tangible sense, masking or dressing up in garments changes people’s perceptions of how to show up in a space, whether or not one should be there, and how space is physically navigated. Lots of ancient African cultures utilized masks for storytelling and transcending time. In this way, I feel that the physical masks I create alter the space I wear them in and those who I can connect to across the work. More metaphorically, Black masculinity requires people to engage in a more intangible masquerade as a coping mechanism and means to survive. Ultimately, masking is a phenomenon with historical and contemporary connections that speaks to a universal experience, even for people outside of the Black community.

ZB: Continuing on the topic of wearable forms, I feel uniquely drawn to this category of your work as a lover of fashion and adornment. Your wearable pieces allow people to become agents and actors in the presentation of the piece, but they also begin to make questions of form more tangible and complicated. The exploration of form and engaging audiences then becomes grounded in the faces, bodies, and people you have in mind while creating. Considering this, who would you say your artwork is for? Does it change based on whether a piece is two-dimensional or wearable?

AS: Hm. First of all, I think it’s for myself. Even then, I feel like the echoes of my reality are connected to other people’s lived experiences. So much of the work has come on account of self-discovery for myself, and I hope it creates the same for other people. Even now, you’re providing an interpretation of my work that reflects your experience.

Still, so much of who the work is for is temporal. What is thought of art, how it is valued and interpreted, are all dependent on who one is as it is encountered. That’s where the variety of material comes in as a tool for connection. My goal is for people to move outside of who they are in their first encounter with the work and be shifted into a state of memory. If the material creates a sense of synesthesia in their mind, that’s what I hope to do. It’s memory work. It’s breaking through the amnesia of something they might have forgotten.

There’s a much larger net that I’m trying to cast with my work that even allows people outside of my diaspora to connect. There are vastly more things that connect one another than diverge from one another. In the vastness of experiences, there is room for art that transcends experiences, time, and connects with other people in a meaningful way.

ZB: Another theme that’s present in your work—and has been in this conversation—is the concept of Black masculinity and the invaluable experience of Black men communing. I know you’re the Creative Director of the Black Man Project, here in Houston. Could you tell me about your work with the project and what it’s meant to you and your artistic practice?

AS: Everyone involved provides great creative contribution, especially Brian Ellison, the founder of the Black Man project. Brian, Marlon Hall, and I were in a church community together. Brian had a desire to help Black men with their mental health through building community, and it came at the right time. I was juggling a lot in my life, and this project allowed me to be in a space where I could take care of myself and be in a space with other men who were doing the same. The Black Man Project also allowed me to extend my reach through my creative practices. We traveled nationally, hosting salons to have men come together and discuss their emotions while equipping them with the tools to continue the work in their community afterwards.

Since COVID, we’ve had the chance to settle more in Houston and engage with other institutions. For example, we’re currently partnered with the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH), where our Wellness Ambassador, Rashad Sanders, hosts meditations and yoga workshops. The beautiful thing about this collaborative phase of the project is the way we’ve been able to birth other efforts. Now we have the Black Woman Project and we’ve been working with children to build more family-focused programming.

ZB: That’s how I first encountered the Black Man Project, at the MFAH with the Kehinde Wiley show that was up at the time. When I visited, I remember thinking that I’d never seen that many Black people in the MFAH before. For the first time, I felt like I belonged there.

To that point, it’s in an interesting time for arts, humanities, and cultural heritage workers. With cuts in federal funding, departments and institutions cutting down staff, and the costs of gallery and studio space increasing, it feels like the places that felt like spaces of belonging are shifting and slipping from our grasp. I’m curious, as an artist and community worker, what does space mean to you? What would you say makes a space yours?

AS: It’s akin to having your own vegetable garden, you know what I mean? Where my studio has been in Third Ward has allowed me to truly be in the community. This is where I’ve felt the most at home.

“There’s something so undeniably powerful about being able to walk down the street and see your history. This space has allowed me to imagine what it was like to have a community before colonialism, where you’re surrounded by the griots, the cooks, the artisans, and everything you need. When you have a space like that, it becomes yours.”

Third Ward represents the best of what I desire for the community to be, and its resilience gives me confidence that we will build a better future.