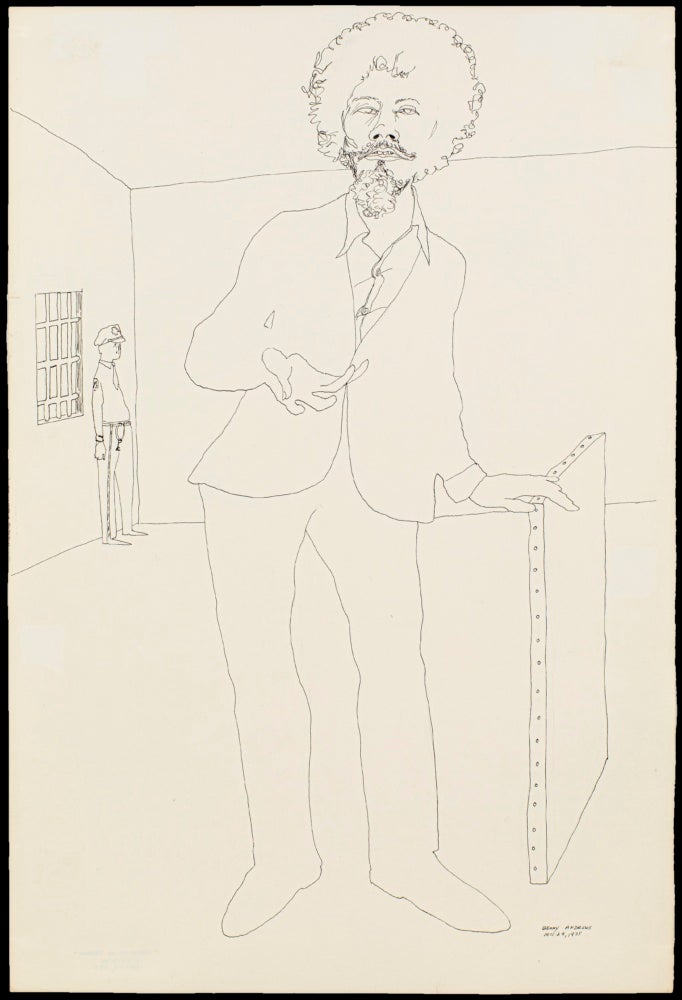

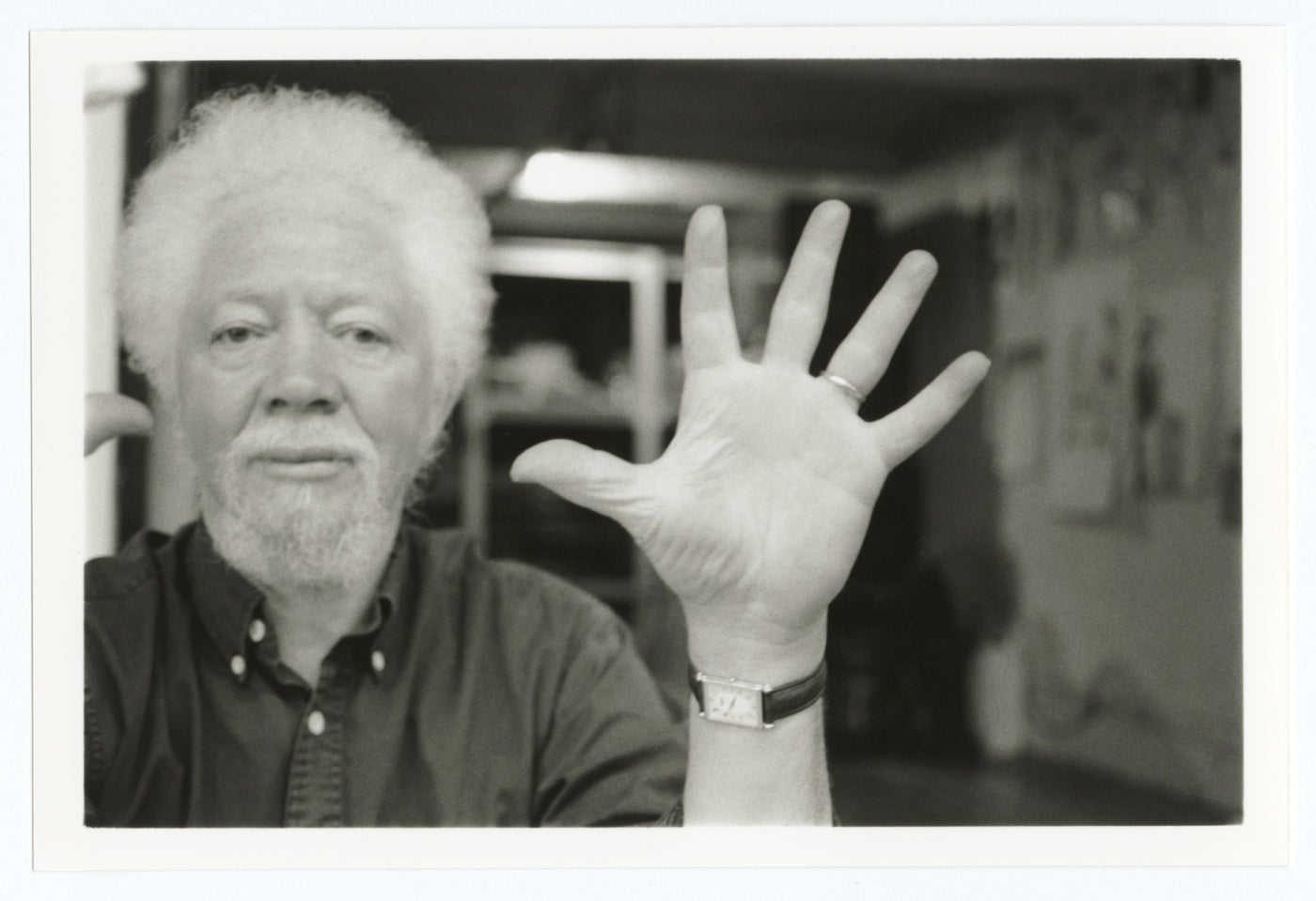

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, NY. Image courtesy of Ruth Arts Foundation, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

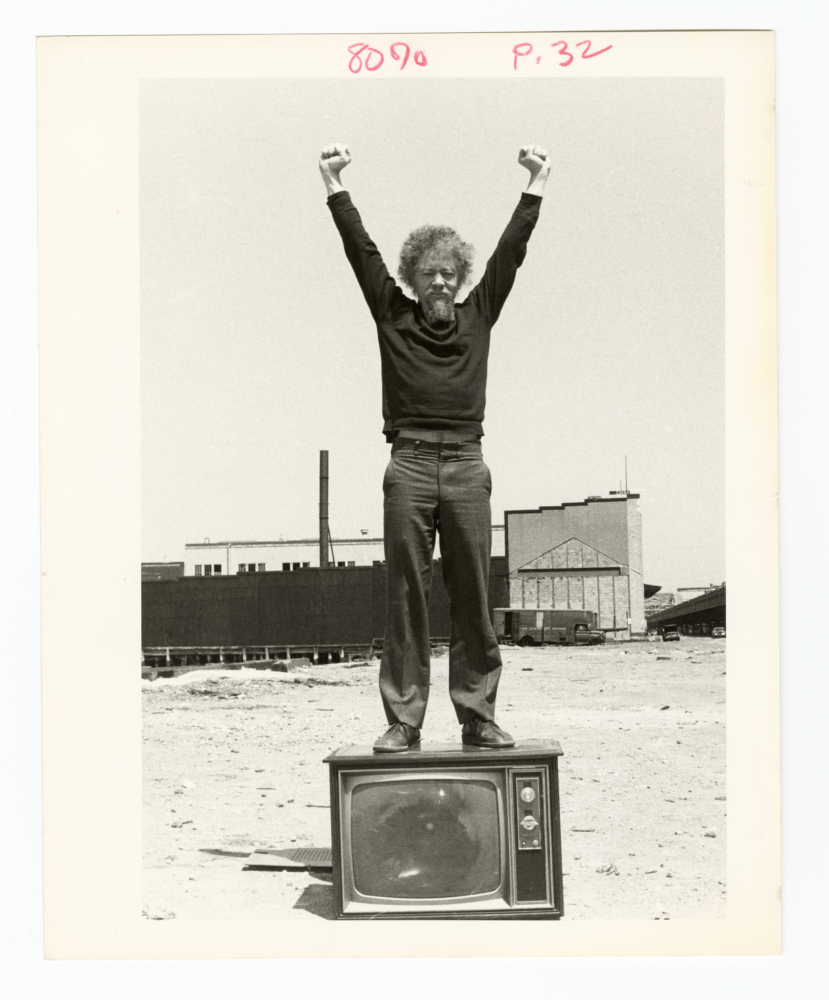

In 1971, a group of men met in a dimly lit room in Lower Manhattan; their voices mixed with the sound of laughter, the shuffle of feet dancing, and the rhythmic scratch of pencils on paper. At first glance, this scene might have resembled an artist’s salon or a lively jazz club—but this was no ordinary gathering of artists or musicians. The room was rather the chapel of the Manhattan House of Detention, more commonly known as the “Tombs.” The men were incarcerated, and the event was not a casual social occasion, but a prison-partnership art class led by the artist-activist and educator Benny Andrews.

Launched in 1971, the Prison Arts Program was developed by the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC).1 This organization, co-founded by Andrews, aimed to increase the rights and representation of Black American artists and arts professionals. While their organizing to protest New York City art institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Whitney Museum of American Art may be what they are most commonly remembered for, nearly two decades of BECC’s work and mission addressed arts education. What began as Andrews teaching a single drawing class in the Tombs soon grew to thirty-seven different programs implemented in mental health facilities, juvenile detention centers, jails, and prisons in fourteen states across the country, including programs in Georgia, Florida, Texas, Mississippi, and North Carolina.

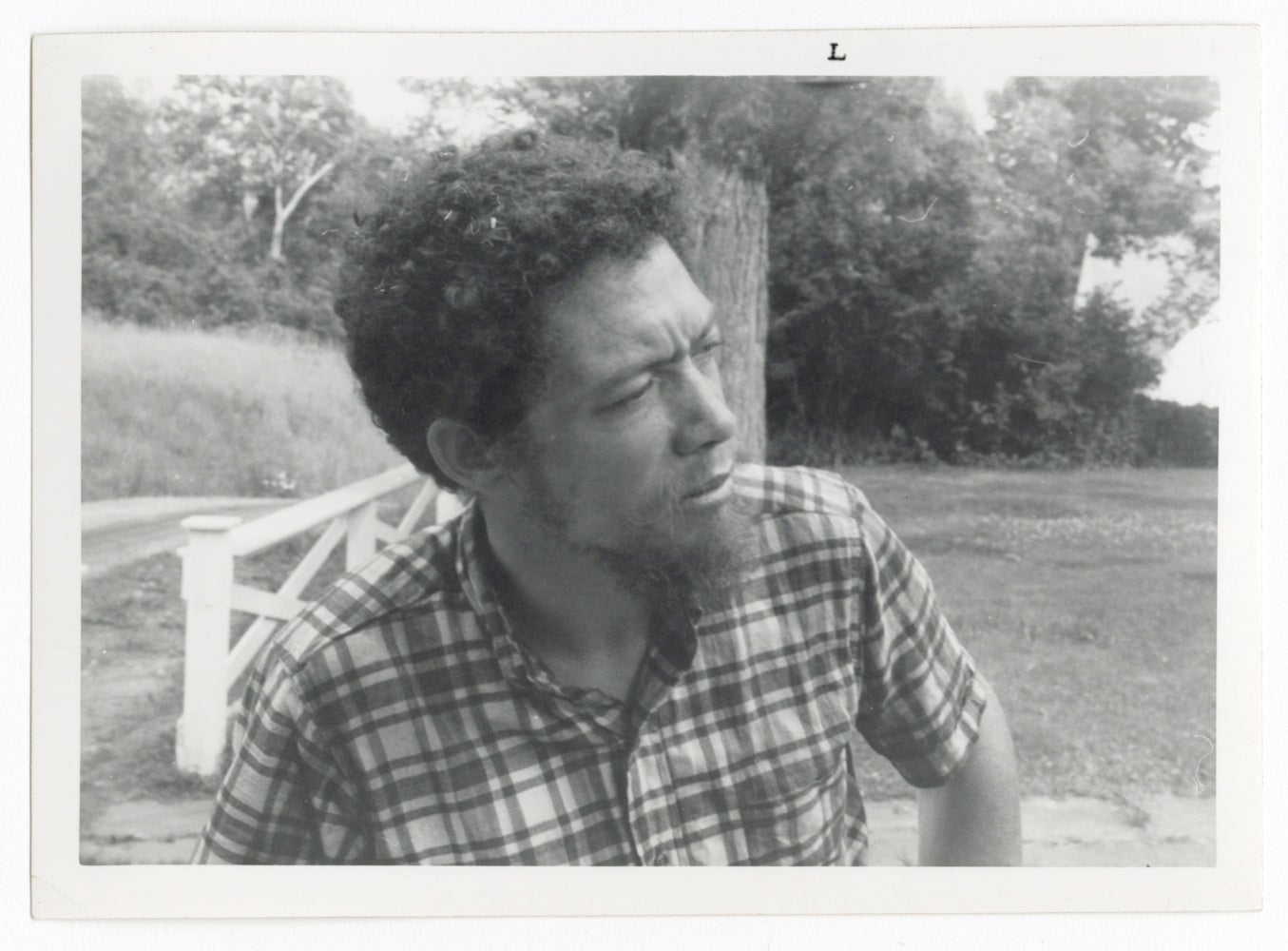

Recognizing the value of education is important to understanding Andrews’s life and practice. His love for education can possibly be traced back to his childhood. Born in Plainview, Georgia, in 1930, Andrews along with the rest of his family worked as sharecroppers on a cotton plantation.2 His mother, Viola, was a staunch believer in education and made a deal with the man that own their plantation to allow Benny to go to school anytime that field work could not be done—predominately during the winter or when it was raining. For him, school became not only an escape from physical labor but a place where his artistic talents were fostered. There, his teachers would allow him to submit drawings and sketches to make up for his missed assignments.3 For Andrews, arts education became education through art. Yes, Andrews had a successful career as an artist, but it would be a grand oversight to ignore his other career as an educator, not only within the Prison Arts Program but also as an art instructor in the Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge (SEEK) program at Queens College.

Walking into his makeshift classroom on his first day at the Tombs, Andrews was aware that the majority of his audience had no interest in art. They, understandably, saw his class as a rare break from their concrete cells, a chance to escape their confinement, if only for an hour. Instead of seeing this disinterest as a hindrance to the class, Andrews leaned into the idea of escapism, using it as a tool to encourage his students to engage with art-making.

Once all of the inmates were settled, Andrews asked the guards to dim the lights. “Before we start drawing,” he began, “we’re just gonna set the scene a little bit.”4 He instructed them to imagine that that they were seated at a table in a swanky night club. “You’ve got your wonderful girlfriend or wife with you,” he continued, “someone you’re really trying to impress.” He went on and on, describing the scene in detail. He told them to picture that the tables were draped in a white tablecloth, with soft candlelight flickering as the big, juicy steak they ordered arrived. As he elaborated, Andrews led his students deeper into their imagination. He invited the students to immerse themselves in the experience to such a depth that they could almost feel the warmth coming off the candles. Later, when Andrews would share with others how he went about starting his classes, he emphasized that it was his goal in those opening moments to make these men believe that they were in another place. A place far from their legal problems, where creativity lived. By utilizing methods of storytelling, he connected his students with the art of drawing.

When the room was buzzing with excitement, Andrews turned to the more daunting task at hand: convincing a room full of self-professed non-artists that they could, in fact, create. He began by asking the group, “How many of you can draw?” As expected, only a couple of hands rose. Unfazed he then asked, “How many of you can write?” In an instant, every hand shot up. This shift in perspective was crucial—if they could write, they could draw. It was the first step in breaking down the misconception that creating art was some inaccessible skill “Now, let’s draw her,” he said, referring to the girlfriend or wife they had just imagined.

With the blackboard behind him, he turned to the group again. “How many of you know how to make the letter C?” All hands went up, and Andrews began drawing two large Cs for the ears. Then he continued, “Who can make Os?” Hands rose again as Andrews made two Os for the eyes. As he continued, sideways Cs became the eyebrows, an L turned into the nose, and another C became a smile—or a frown “if she’s mad at you.” Each shape built on the last, the letters transforming into a simple but recognizable face. With each stroke, the room’s confidence grew. What had seemed daunting moments before now felt within reach, and Andrews had done more than just teach them to draw—he had shown them how to rethink what was possible.

In a series of drafted manuscripts Andrews shares pertinent reflections on his first handful of classes at the Tombs. He reflects on how his teaching practice was able to create an oasis in which creativity and personal expression could thrive. In his second visit to the Tombs, Andrews notes that the chapel was alive with music, one man on the piano, another on the drums, both completely engrossed in their performance. To Andrews, it was as though “the piano player was far away, somewhere with no bars or guards, where he had spent thirty-five years as a brilliant pianist. The drummer, whoever he was, wasn’t mentally in jail at that moment either.”5

Their music, their art, was an escape that transported Andrews’s students beyond their current reality. As the inmates began to draw, the energy in the room grew with each chord. Other students worked feverishly, pausing only to cheer on the musicians or to call for Andrews. He flew through the room, “like a helicopter,” his attention in high demand as the students vied for his feedback.6 The energy was so infectious that even the guards found themselves, departing from their usually strict demeanor, swept up in the moment. Andrews described the guards as “caught up in the feeling of it all, acting like waiters, passing out pencils and sketch pads.” When Andrews asked if the students could move around the room, the guards just shrugged, their expressions almost saying, “Man, the way this session’s going, they could all go free for all I care.”7 In that moment, the lines between prisoner and free man, teacher and student, seemed to melt away, leaving only the shared experience of creation within that brief but powerful sense of escape. The chapel was alive with a rare sense of hope and freedom, feelings that were often hard to come by within the walls of the Manhattan House of Detention.

As outlined in the Prison Arts Program’s initial 1971 proposal to the Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Bronx Houses of Detention, the goals of the program were “to motivate and educate prison inmates with demonstrated and potential talent in art, to offer a program of art appreciation through continuous exhibitions of professional artists’ works along with lectures, slides, and seminars held within the prison, and to support the exhibition of outstanding prison artists’ works in galleries, museums, and centers outside the prison.”8 In describing the purpose of the program, Andrews and his co-organizers often emphasized that their aim was not to produce output for profit or guarantee people jobs. This is not to say that they did not help students who did wish to pursue a career in “artmaking and the wider art world,” many did, some even became instructors in the program.9 However, they rejected the idea that the inmates should create work or “crafts” to be sold by the prison for a return. Instead, they focused almost exclusively on the importance of self-expression for incarcerated individuals. According to Andrews, this philosophy helped them gain acceptance by the inmates. He explained, “Once they realize that [the BECC] are not trying to rehabilitate them or get them to turn out crafts for the prison store, they are more open to the idea of art classes.”10 These philosophies reflected Andrews’s approach to teaching them how to draw. It was not about the quality of work, rather what the men felt they got out of it.

In that moment, the lines between prisoner and free man, teacher and student, seemed to melt away, leaving only the shared experience of creation within that brief but powerful sense of escape.

The BECC’s Prison Arts Program, reflected Andrews’s belief that art had more than just aesthetic benefits, it could impact a person’s life. By prioritizing self-expression and personal growth over commercial gain Andrews created an environment where creativity became a form of escape, empowerment, and self-discovery. Through his innovative teaching methods rooted in forming community Andrews not only brought life and energy into the stark confines of prison walls but also left a lasting legacy that challenged societal perceptions of who could participate in and benefit from artistic expression. By taking art where it was not meant to be Andrews and his co organizers transcended traditional boundaries of art education and the wider art world. Their work serves as a testament to the enduring capacity of art to inspire hope, foster connection, and affirm the dignity of all individuals, regardless of their circumstances.

[1] BECC Newsletter, 1980, box 32, Benny Andrews Estate, New York.

[2] Benny Andrews, “The Art of Benny Andrews: A 1975 Interview with Phil and Linda R. Williams,” The Georgia Review, https://www.thegeorgiareview.com/posts/the-art-of-benny-andrews-a-1975-interview-with-phil-and-linda-r-williams/. This interview first appeared in the fourth issue of Ataraxia, edited by Phil Williams and Linda R. Williams.

[3] Andrews, “The Art of Benny Andrews.”

[4] Nene Humphry (wife of Andrews from 1986 until his death in 2006), in discussion with the author, June 26, 2024.

[5] Benny Andrews, “Toombs: My First Visits to Teach,” 1973, Benny Andrews Estate, New York, p. 2. This draft along with two other essays were ultimately edited together and published as “I Teach Painting in Prisons and I Find a Cry For Love” in the Art Material Trade News, Volume XXV No. 6, June 1973.

[6] Andrews, “Toombs,” p. 1.

[7] Andrews, “Toombs,” p. 2.

[8] “Draft Proposal on Prison Arts Program,” 1971, box 34, Benny Andrews Estate, New York, p. 2.

[9] Nadia Scott, “Where It’s Not Meant to Be: Benny Andrews and the Prison Arts Program,” p. 2. Originally written for the exhibition Benny Andrews: Trouble on view at Ruth Arts in Milwaukee, WI from September 2024 to February 2025.

[10] Benny Andrews, “Should Art Be Taught in the Prisons,” ca. 1970, Benny Andrews Estate, New York, p. 2.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Knock Knock.