I found History Painting #1 (for B.N.) sticking out of the mud. On September 27, unprecedented water from Hurricane Helene swelled the Swannanoa River, raising it 19 feet in twenty hours.1 There were no witnesses inside the Southside Studios building, where my studio space was, as it flooded. I picture what happened there, working backward from the evidence.

I see water pouring into the sides of the building, in the darkness of night, eventually lifting every painting on my studio walls off its hooks, dumping the contents of my shelves, mixing my paint, my tools, the clay and glaze buckets from my ceramic projects, and twenty years of sketchbooks, drawings, prints, paintings, catalogs, false starts, weird experiments, and beloved successes into a dystopian studio tea.

My space is on the river side of the building. Eventually, the water filling the entire warehouse must have drained back out through my studio, leaving a pile of my life’s art inventory facedown, dumped in the center, and covered in two feet of mud.

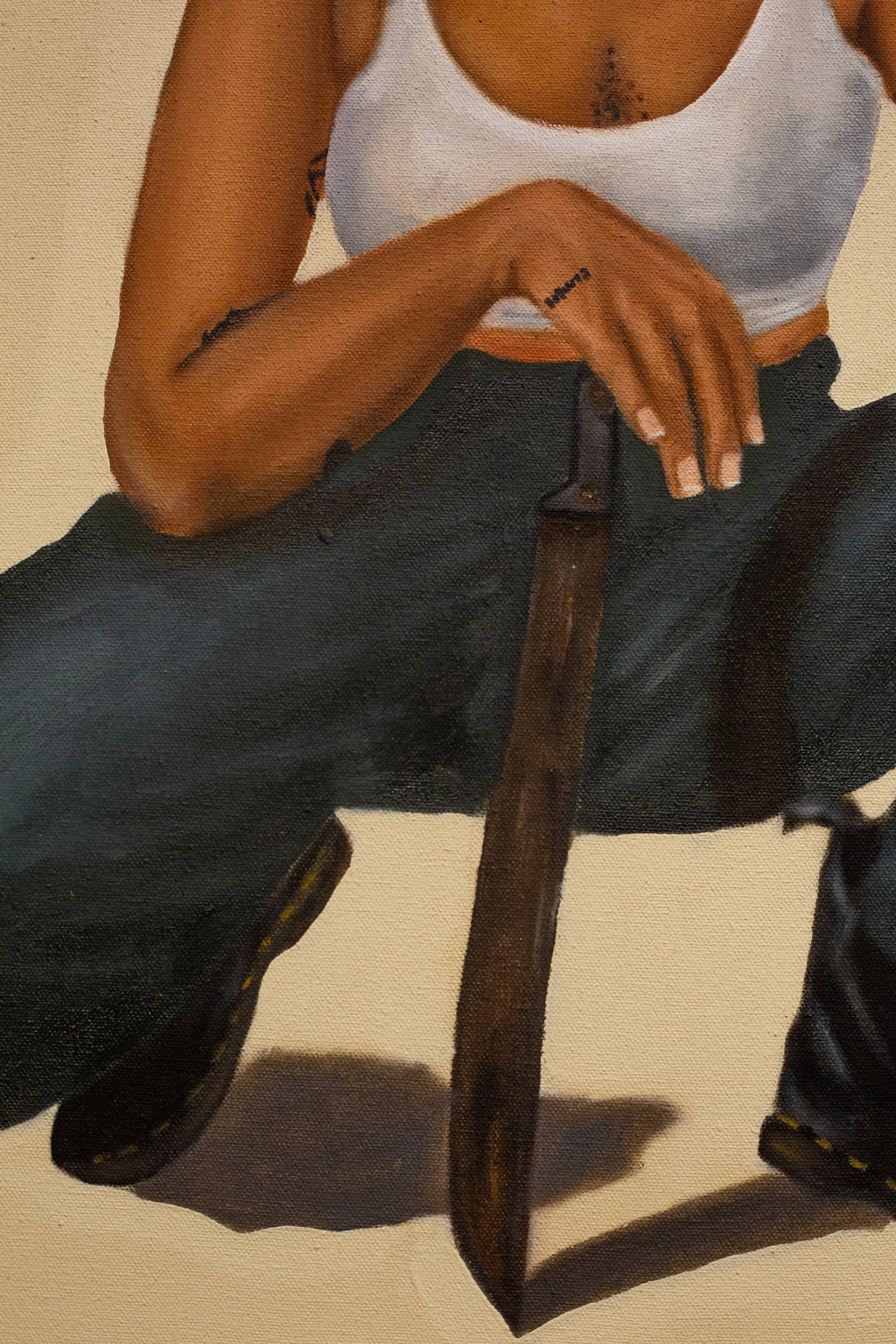

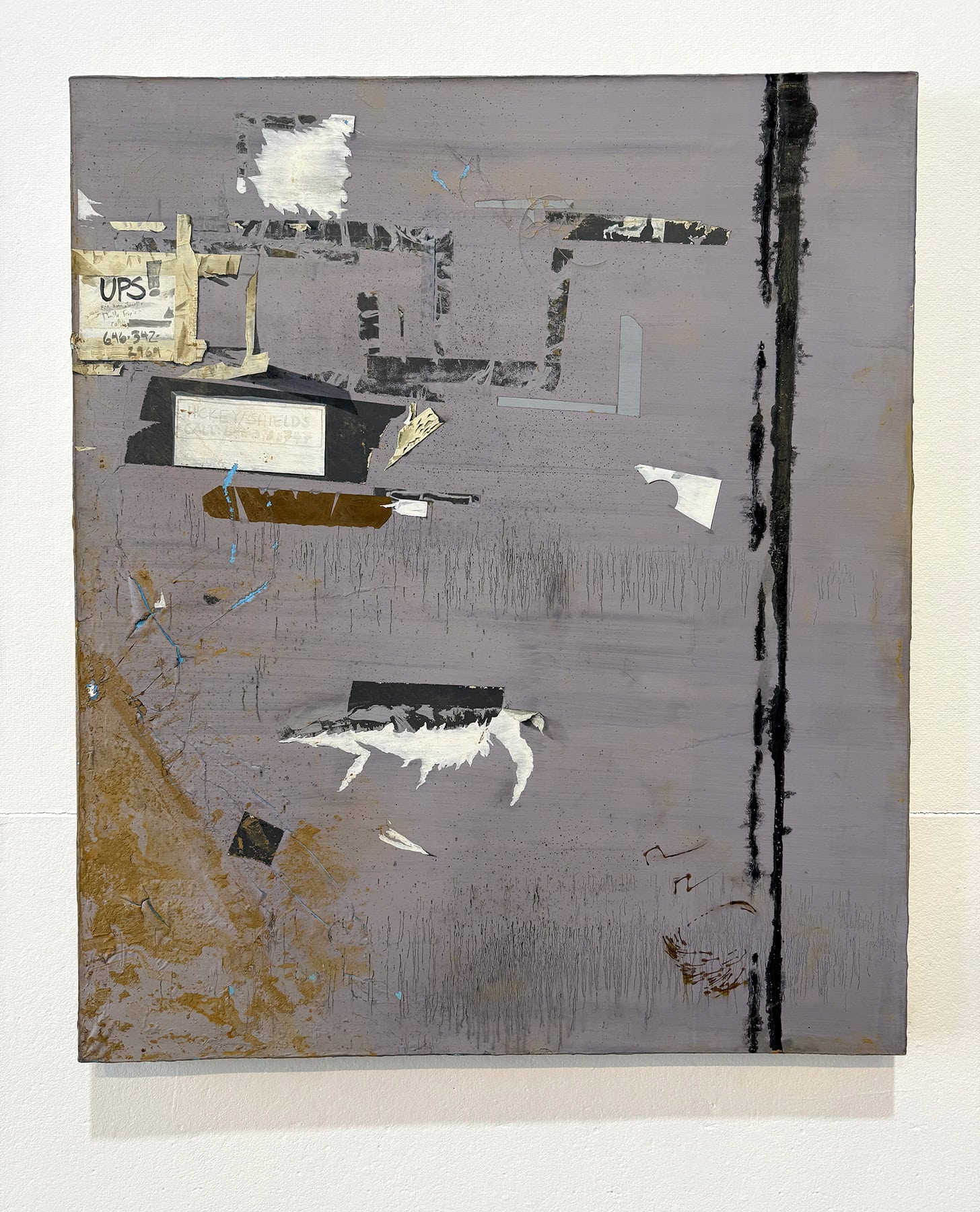

When I look at History Painting, I see spiral cracks in the paint, indicating places where objects forcefully hit it, as unloosed objects sloshed inside the studio, and runaway shipping containers slammed the outside walls in the raging water. A layer of mud coats the work, especially on the bottom half where the stretcher bars caught the receding river mud. Where the water soaked it the longest, the upper layers of paint are bubbled and peeling, revealing the blue sky of a recycled painting underneath.

History Painting #1 (for B.N.) was initially about a personal transition, and layers–literal and figurative–of history. It’s the first painting I made when I moved to New York City. The door to my studio building in Brooklyn had an accumulation of the small, unremarkable histories of the artists working inside. Notes left for visiting clients and UPS–taped, torn down, repainted, retaped. What attracted me to the door was a dark double line of rust that reminded me of the mid-twentieth-century American painter Barnett Newman, known for his large paintings with a line that he called a “zip.”

Eight years after I made History Painting, my partner and I decided to move to Asheville, North Carolina. The very first thing I noticed when I got here was how lush it is. It’s a temperate rainforest in the mountains, and weeds flourish in every crevice, even in the most cement-dense parts of the city. I paint what I see in my daily life, and my New York palette had a lot of grey. When I moved to Asheville, I bought ten new shades of green paint.

It was then that I started painting weeds. They are nature without permission, and beauty inside what is common and overlooked. They embody the tough, DIY spirit of the region.

Painters often joke that they “push around colored mud.” In History Painting #1 (for B.N.), Nature, without my permission, has painted its own layer of mud on top of mine.

What is the suffering of losing my life’s work? I don’t honestly yet know. But a big part of it is the lack of witness.

Much of what I lost, no one ever knew existed. Many of us in this region have suffered unimaginable loss. Everyone hurts, and there’s no value in ranking. But there is a unique feeling of loneliness in losing my studio. Most of what is gone was already invisible to everyone but me. It was my experiments, my not-yet-realized ideas inside sketchbooks, and my weirdest, least public-facing work. And though I can gather paint and brushes into a workspace again, the paintings that were destroyed can never be replaced.

The studio and all it contained was the “room of my own.”2 It was the output of my creativity, my years of training and practice. It was the tendrils that may have become the next year or the next decade’s work. My studio is where I reach a flow state, and time stops. Privacy is a feature. This space is where I crystallize my life’s joys and crises into art objects. And now that I’ve lost those memories, that history, those experiences-turned-art, the privacy of my process has become a source of pain. I didn’t just lose my art. I lost my personal history.

I have a parallel life, in a company I founded called Sunlight Tax, where I teach artists and other creative people how to manage the tax side of their self-employment. I find joy in helping my fellow creatives in a way that contrasts with the hermetic work I do as an artist. With teaching taxes, I get immediate feedback and fellowship. Art is slower, riskier, tenderer, and more solitary.

In the wake of Helene, people ask me what comes next. Here’s where I am: I set up a desk in a tiny space in my laundry room. For now, I don’t need much studio space because, frankly, my stuff is mostly gone. Tax education is seasonal; I don’t plan to hunker down in my micro studio until after April 15.

I don’t know what will happen when I get in there. Will I bawl for days? Will I have digested any of this tragedy, and will that come out in my work? Will I make a bunch of frustrating false starts? Will I have too much feeling to form a cogent design thought? Will I scrap every idea that came before and start something totally new?

Great art isn’t guaranteed, and it isn’t predetermined. It’s not a widget. It is a distillation of the experience of a human being, in one time and place, with a skillset, an idea, and a feeling. I can only create the conditions and put in the hours. I will stand in front of that blank canvas, and I can tell you this with certainty: I don’t know what will happen next.

1. Skinner, Anna. “North Carolina River Breaks 230 Year Old Record during Hurricane Helene.” Newsweek, September 28, 2024. https://www.newsweek.com/north-carolina-asheville-swannanoa-river-flooding-breaks-record-hurricane-helene-1960619.

2. Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Orlando, Fla: Harcourt, 2005.