The exhibition Public Domain: Photography and the Preservation of Public Lands at the Asheville Art Museum commemorates the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the US Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, “whose mission is to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.” It’s fitting that Asheville, a city tucked in the Blue Ridge Mountains, should honor this otherwise overlooked anniversary. Driving on the Blue Ridge Parkway is enough to bring a momentary feeling of patriotism.

In the quiet museum, around two-dozen landscape photographs fill a small cave of a gallery. The photographs—depicting state and federally managed lands across the United States, including the Smoky Mountains, Big Sur, Pisgah National Forest, and the Blue Ridge Mountains—are at once celebratory and quietly critical.

At the entrance is a bucolic scene of Ohio foliage surrounding a waterfall. It’s as pretty and plain as a highway rest stop postcard. Only the accompanying wall text disrupts this facade: the waterfall is actually toxic. Its water powers a nearby industrial site, which, in turn, pollutes the water. When the artist Robert Glenn Ketchum took the photograph in 1986, the soil surrounding the falls was still soaked in waste.

The photo hanging next to this one—a verdant meadow in the same Ohio park—is similarly idyllic. I interrogate the picture for signs of wrongdoing. Do my eyes deceive me or is that grass too green, those flowers too cheerful?

As it turns out, the Bureau of Land Management allows for private use and “natural-resource management” in some parts of public land. Their mismanagement has led to erosion, deforestation, overgrazing, and other disasters. When Glenn Ketchum’s photo series Overlooked in America: The Success and Failure of Federal Land Management was published by Aperture thirty years ago, it was an explicit condemnation of the government’s (lack of) care for its public land, and a warning of what was at stake.

The most arresting moment in Public Domain is a series of four photographs from the Overlooked in America series. The first three are mostly unremarkable—they depict the dense autumnal brush of Ohio’s Cuyahoga Valley National Park. The fourth exposes the Bureau’s failure: in the foreground, a hill of black rubber tires and in the distance, a pile of metallic refuse. This is Krejci Dump, a privately-owned landfill that was incorporated into the National Park in 1985. The photograph was taken a year later. Cleanup began that same year and was finally completed in 2020. The change in colors between the warmth of the first three and the melancholic blue of the fourth is dramatic, almost cinematic, as if the curtain has been pulled back on our vision of nature to reveal our hubris.

Federal Land Projects are one attempt at correcting the course of environmental degradation in the US. Not a reforesting, or a return of land to Indigenous peoples, but another form of control that is an extension of manifest destiny.

Mercifully, Public Domain is not overtly cynical. If it’s an indictment of the failures of the Federal Land Projects, it’s a gentle one. In fact, the critique of federal land management might be missed altogether should a visitor choose not to read the exhibition’s wall labels.

Next door to the rolling hills of Public Domain is another exhibition of capitalist degradation: Our Strength is Our People: The Humanist Photographs of Lewis Hine. Entering the gallery doors is like having another curtain pulled back to reveal the missing people from those conspicuously empty landscapes. These photographs are busily-peopled, cluttered, grimy, teeming, and hot. When seen in tandem some alchemy occurs between these exhibitions so that together they are greater than the sum of their parts. Were I rushing somewhere and forced to be concise, I would say the two exhibitions complement one another.

Our Strength is Our People traces the career of Lewis Hine (1874—1940) a leading figure in American documentary photography. The three overarching themes of Hine’s career—the immigrant experience, child labor, and the working class— are laid out in 65 black-and-white photographs.

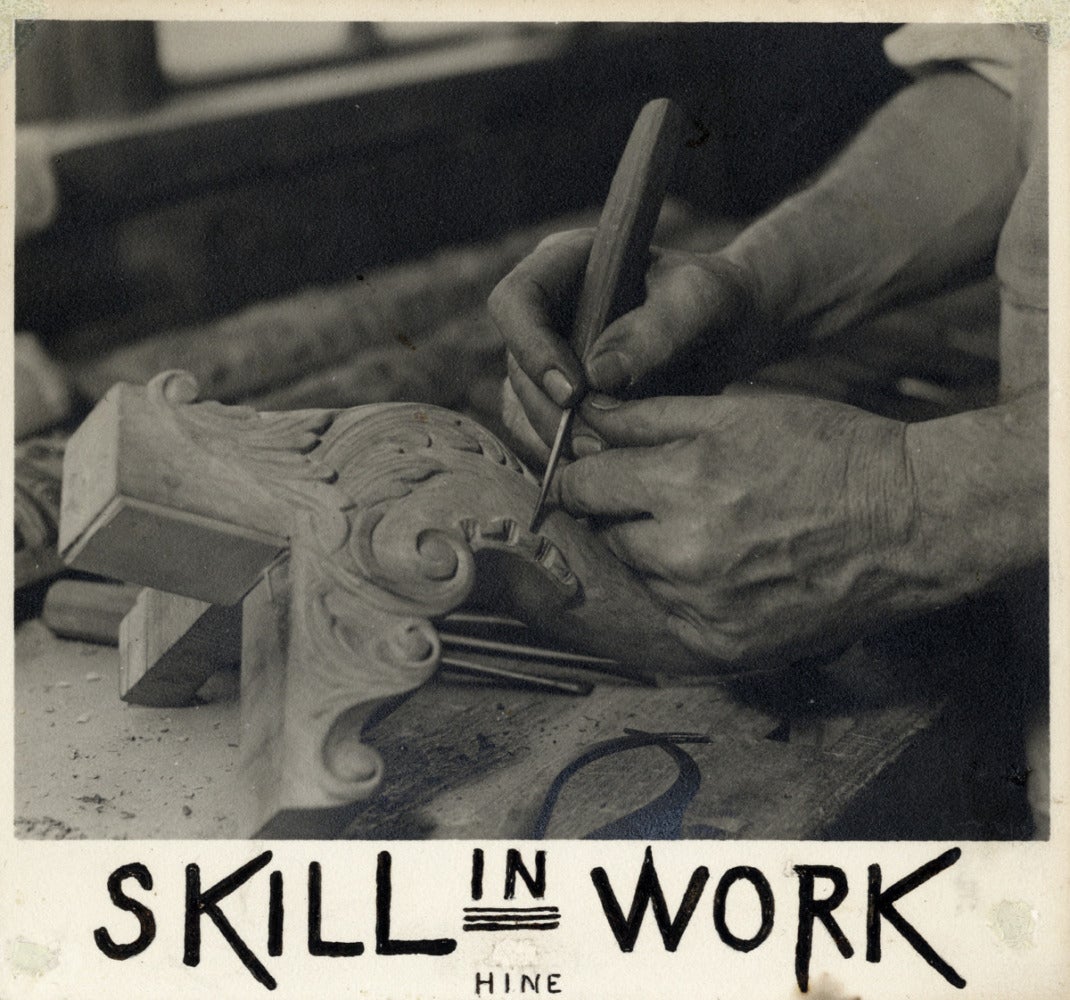

A photograph of adroit hands carving delicate wooden flourishes declares below it in handwritten letters: SKILL IN WORK. Elsewhere, a muscled worker at a Pennsylvania rubber company deftly handles a control wheel. Hine cleverly duplicated the photograph to give us four perspectives of the man-machine chimera. These are the workers turning the machines of industry, the refuse of which will one day seep out into soil, stream, and sky, and will, one day, be cleaned up.

Hine meant for his photographs to be a corrective. Between 1908 and 1924 Hine produced investigative photographs for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), which used his images to lobby for child labor laws. His reverent portraits of immigrants and the working class still hold enormous redemptive potential today.

The photographs provide us an intimate encounter with their subjects. I can feel the hum of the factory but the focus is on the sitter. See how the sleeves of her dress billow much like her hair piled on top of her head? See the endless stretch of painted glass behind her, the product of her deep concentration? Lest you make the error of thinking our country’s newest arrivals are only worth the labor they expend, Hine treats them with dignity in moments of rest and play, too, shooting the breeze between shifts, sharing cigarettes.

Hine said, “Much emphasis is being put upon the dangers inherent in our alien groups, our unassimilated or even partly Americanized citizens—criticism based upon insufficient knowledge. A corrective for this would be better facilities for seeing, and so understanding what the facts are.”

The facts are these:

Little boys dressed in black and standing in a line, their faces dirty, are cotton mill workers. What looks like boys playing pretend is not pretending at all—that’s not a candy cigarette dangling from that child’s mouth. The label says one of the boys pictured began work at three years old. Three! How absurd! How unbelievable! How laughable—not haha-funny but laugh-to-keep-from-crying-funny.

Meanwhile, directly outside the museum, another correction is taking place: the Zebulon Baird Vance Monument, an obelisk honoring the former North Carolina governor, enslaver, and grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, is being removed from Pack Square, the center of town.

Between the spaces of these two galleries and the plaza outside, I begin to see the US as one gargantuan Rube Goldberg contraption, endlessly spinning and turning and correcting. Attach a pipe here, watch smoke spill out, plug it up. Dig a hole, fill it back up. Make a spill, cover it up. Station a child here, pass a law, take him out. Build a tower, tear it down. Bury some waste and watch it erupt, now put a cap on it and listen to it hum.

Public Domain: Photography and the Preservation of Public Lands is on view thru August 30, 2021.

Our Strength Is Our People: The Humanist Photographs of Lewis Hine is on view thru August 2, 2021.